[Editor’s note: On Feb. 7, Tyee founding editor David Beers delivered the Harvey Stevenson Southam Lecture at the University of Victoria to a full house audience. The talk was video recorded and can be viewed above. We present as well the text in two parts, running today and tomorrow.]

Let’s face it. We can all feel it. The ground is shifting beneath us. It feels as if a void is replacing the solid if squeaky floor we all took for granted.

The floor I’m speaking of is a simple, basic shared assumption:

That however we might disagree ideologically, our conversation must begin with shared facts. Because from such facts can flow reasonable decisions.

The assumption that knowing the facts is essential to holding accountable those to whom we’ve entrusted power.

That having facts on one’s side, when push comes to shove in our democratic discourse, is how to be strong and succeed.

That liars and fantasists might catch our attention for a moment the way circus clowns do. But they will be found out. Shown up. Discredited as weak fools who just gum up the democratic conversation in which we must engage.

All this we have assumed because we live in a material, tangible world and so the consequences of decisions made by those in power can be researched and reported as facts.

The prime source of such facts for the citizenry, for the last century here in Canada, has been the news media.

Its job description has been a big one. Harvest facts global, national, regional, local and hyper-local — all the news fit to print about who did what yesterday and today and what they are hankering to do tomorrow.

Harvest too, the facts that no one puts in a press release — facts that can be pried loose only by proactive investigation.

We call the people who do this job journalists.

And, until the last decade or so, nobody worried about the well-being of journalists, much less the ongoing existence of their role in society, because, like roads and schools and supermarkets, they were basic infrastructure.

I am going to argue that journalists are increasingly endangered in Canada not because — as in other countries such as the Philippines, Mexico or Russia — they are actually jailed or murdered by those who are threatened by their fact finding.

The slow liquidation of the ranks of journalists in this country is being carried out by other methods. Including:

- The destruction of an economic model that we took for granted.

- The resulting drying up of resources to do the kind of journalism that is rigorous, ethical, responsible journalism carried out in the public interest.

- The erosion of journalists’ standing in our democratic conversation because the internet changed the power dynamics.

- The increasing mental health hazards of doing journalism, including injuries inflicted by vicious online trolling.

- A global movement that aims to destabilize democracies and replace them with modes of government that hew towards authoritarianism. This movement has, again and again, named journalists its enemies.

About number five. At this moment when democracy is back on its heels so obviously just to our south and around the world, Canadians should not consider themselves immune from similar conditions.

Foes of democracy who are would-be autocrats must first destroy a shared sense of reality — and there is evidence we are headed down that path.

Indeed, the war on journalists, as I will argue, is part of a war on reality itself.

I will argue that this war is allowed to gain steam because Canadians’ awareness of what is at stake, and our national response to date, is thin.

Here is a definition of war by scientist and philosopher Jacob Bronowski. He terms it “a highly planned and co-operative form of theft.”

And so the question arises. Who seeks to steal from us journalism in the public interest, which happens to be a bulwark of democracy?

Which invites further questions commonly asked by investigative journalists.

Who stands to benefit?

Who would gain from so massive a disruption?

Let me tell you a bit of my background, and in the process share with you a more elaborate definition of what I mean by a public interest journalist.

I grew up in California’s Santa Clara Valley as it was becoming Silicon Valley.

I held progressive values from an early age, and through my education and the books and magazines and newspapers I read came to believe, as Martin Luther King stated, “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.”

I was a Watergate kid, who saw investigative reporting not only expose a president’s lawbreaking but help halt the Vietnam war, alert us to environmental threats, and shift society towards positive social change in myriad other ways.

As a young journalist I reported on refugees from a scorched earth campaign waged by the U.S.-backed military regime in Guatemala, and chronicled the precarious work forces of California’s farm fields and tech plants.

I gathered visual evidence with my camera, and fact upon fact in my notebooks.

By the time I’d become an editor and writer at Mother Jones magazine in the late ‘80s, the rules were clear to me. To be a journalist with any impact required adhering to rigorous methods.

Mother Jones’s fact-checking department verified every word in every piece we published.

We understood that the issues we chose to investigate, the questions we chose to pursue, were informed by progressive values.

Nevertheless, the floor we built our muckraking magazine upon had to be thoroughly buttressed. It had to be rock solid, in the face of challenge by anyone.

Otherwise, the information we sought to share could be easily dismissed as cant, and we’d be denied participation in the wider democratic conversation.

The price of admission to that vital exchange was fact-based credibility.

Were we activists? Am I an activist? Emphatically I say no. I’ve always understood the lane I chose and have stayed in it.

The journalistic principles I adhered to at Mother Jones I’d adhered to previously, when I was a writer and editor for the Hearst corporation-owned San Francisco Examiner, and later when I wrote for National Geographic or Vancouver Magazine or the Los Angeles Times, or still later when I served as an editor at the Vancouver Sun.

They are the same principles that define The Tyee, which I founded in Vancouver 20 years ago.

We at The Tyee abide by a code that insists we must be able to substantiate and verify anything we publish. We understand there are substantial consequences when we fail. Beyond professional humiliation and loss of credibility, there lies the potential of being sued for libel.

So yes, it is possible to be a person with progressive values who understands the overriding value of journalism’s values — talking to all sides, reporting for context and nuance and getting it right. Insuring the story could live on its own among skeptical readers who demanded facts over spin.

As a young journalist I readily accepted these strictures and understood them to be the harness one slipped on if you expected to command wide attention, which in turn was necessary to make an impact towards positive social change.

Let us pause to contemplate which figures, just a few decades later, dominate the political conversation today in the nation where I came of age.

The output of the entire staff of the New York Times merits 9.6 million paid digital subscribers. Each Spotify podcast by Joe Rogan, a former standup comic and reality TV show host, has 12 million subscribers and reportedly pulls in 11 million listeners per episode.

Joe Rogan is anything but a journalist restrained by the code I described. By his own admission, “I talk shit for a living.” When criticized because he put lives at risk by giving a favourable platform to anti-vax quacks, he shrugged and apologized for not bothering to vet his guests before putting them on, but said he would try and do better.

Consider the bizarre offerings of Tucker Carlson on Fox News, whose cable TV leading average nightly audience has often topped 4 million. Carlson has said there is no such thing as a white supremacist and that Trump’s foes were the ones who organized the assault on the Capitol.

He has devoted many shows to the premise that "the end of men" is nigh — but it might be staved off if men spent more time exposing their testicles to sunlight.

But then Carlson has defended himself from libel suits by his lawyers arguing he should never be considered anything like a journalist and people should not take him seriously.

In fact, here is a 2021 quote from Tucker Carlson. “I lie. I really try not to. I try never to lie on TV. I just don’t — I don’t like lying. I certainly do it, you know, out of weakness or whatever.”

In February, the admitted liar Carlson, who’s relentlessly defended the champion liar Donald Trump, defended the natural product of our times, newly installed member of Congress George Santos, who has lied, it seems about everything — his name, his election money, his resume, his Ponzi scheme grift, his college diplomas and even his fake volleyball stardom.

Did the floor beneath us just melt away a little more? Are you feeling queasier?

We in Canada cannot escape the undertow, because the internet knows no borders. The sort of nonsense I’ve just referenced lives on and resonates via the web’s echo chambers.

In January of last year Elon Musk declared Canada’s government illegitimate. His evidence? Pictures of lots of angry truckers rolling into Ottawa.

He told his then 63 million Twitter followers, “It would appear that the so-called ‘fringe minority’ is actually the government.”

And: “If the government had the mandate of the people, there would be a significant counter-protest. There is not, therefore they do not.”

He said this as if pointing to the inevitable output of one of his engineering equations.

Musk’s logic of course fails basic tests. Nearly 90 per cent of Canada’s truckers were vaccinated, so the convoy was not representative even of drivers, much less the nearly three out of four polled Canadians who believe truckers should be vaccinated or have to prove they are COVID-free at the border.

Musk also ignored the actual far-right “fringe minority” extremists tied to the convoy and the hate some of them spew.

In the year since, Musk’s Twitter following has doubled to 128 million followers and of course he now owns the platform.

Musk’s first tweets upon taking ownership were to spread a baseless story smearing the husband of the U.S. Speaker of the House, who was assaulted with a hammer in his home by a stranger, who himself was an unhinged disciple of Trump’s big lie about a stolen presidential election.

It took actual journalists very little time to debunk that fake news.

But Musk plainly has little regard for journalists. To him, they are not normal people. Journalists “think they're better than everyone else” he said after suspending some from Twitter.

He later amended: “Not all journalists are bad, but far too many are.”

Meanwhile he dissolved Twitter’s panel that checks postings for their truthfulness, fired much of Twitter’s team focused on combating misinformation, and reinstated the accounts of a number of proven, persistent purveyors of lies.

This caused Reporters without Borders and the Committee to Protect Journalists to send him a letter voicing “alarm.”

Whether Musk believes members of those organizations to be among the far too many bad journalists we don’t know.

We do know that he himself is prime spreader of misinformation on Twitter, promoting fact-free narratives about, for example, the pandemic. Early on, he said it would be over in a month and railed against public health measures.

Recently he has absurdly called for the prosecution of former chief White House medical advisor Anthony Fauci.

Why would Elon Musk spend $44 billion to buy so important a platform for conducting our democratic conversation and then do his best to make it a swamp for misinformation?

Tech barons need good info to succeed, do they not?

Why demonize journalists, when so many inhabit his platform?

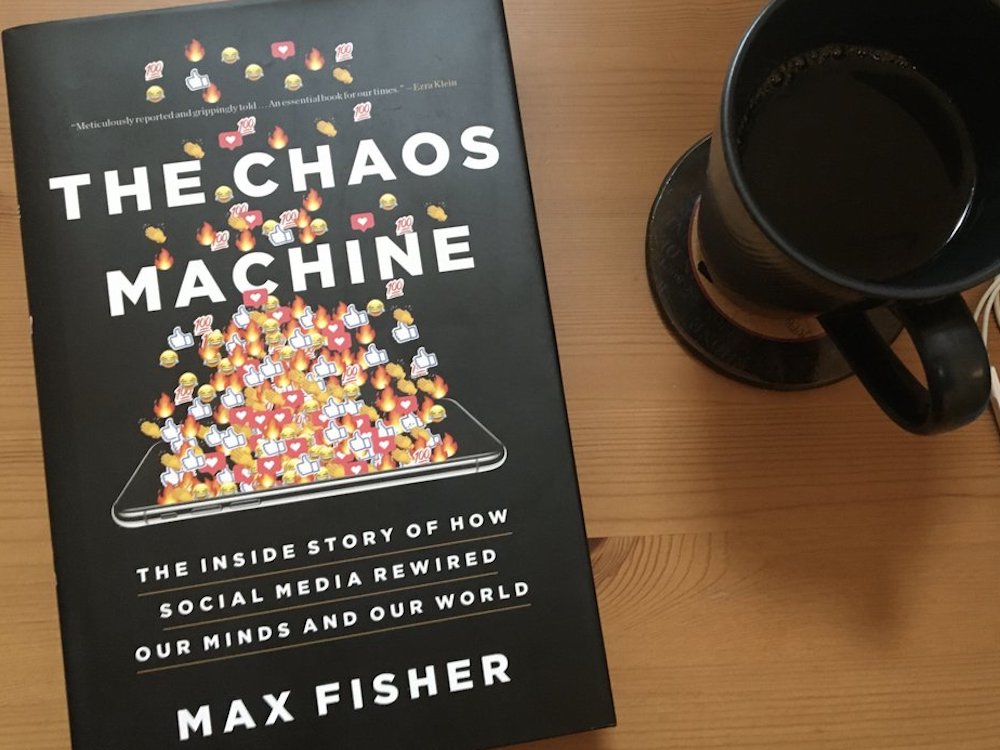

In his brilliant new book The Chaos Machine about the rise and impact of social media, New York Times reporter Max Fisher documents the anti-democratic philosophies that guide some of our most powerful tech barons. In a December series of tweets Fisher tells it this way:

“People really need to understand how mainstream it has become in some tech venture capital circles to argue that journalism itself is dangerous as an idea and should be abolished, and that it will be up to the tech world to carry this out.

“It comes out of a Silicon Valley utopianism that has said since the ‘90s that all legacy institutions are ultimately barriers to progress, but that the enlightened minds of the tech world, guided by the pure science of engineering, will one day liberate us by smashing the old ways.” Fisher goes on to say:

“The idea of rejecting institutions to build a purer society on the internet, in vogue in tech in the ‘90s, by the 2010s had become a mandate to abolish and remake those institutions in Big Tech's image.”

Fisher’s book quotes a 22-year-old Mark Zuckerberg perceiving society as mere code to be hacked, saying: “I can break down this system and make it better.”

The book also quotes Peter Thiel proclaiming, in 2009, “I no longer believe freedom and democracy are compatible.” Thiel, who co-founded PayPal with Musk, is a major financial backer of Trump and other Make American Great Again candidates.

Fisher quotes Thiel concluding: “Only companies like Facebook” could safeguard liberty.

And only, writes Fisher paraphrasing Thiel, “if companies like Facebook were unshackled from ‘politics,’ which seems to mean regulation, public accountability and possibly the law.”

By 2020 top Silicon Valley venture capitalists were gathering on a private online site called the Clubhouse to openly question whether journalists should even have the right to investigate private companies. They were mad that journalists find out stuff which prevents tech founders from attracting and making lots of money while they remake society.

In his tweet thread, Fisher sums up their self-serving rubric.

“Their deep belief is that the defining battle of our time is between tech companies that want to liberate us and dying institutions like the news media trying to halt that progress out of a desperate bid for survival. Only by destroying those institutions can Big Tech save humanity.”

He goes on: “There's been a movement for a few years now among many of Big Tech's most powerful venture capitalists to mass block, even try to harass or ban, news reporters as a class. Journalism is unwelcome in the new digital utopia.

“And that's the circle from which a certain new Twitter CEO comes,” says Fisher.

Of course, not every early believer in the transformative effects of the internet were so adamantly anti-democratic.

For some high profile thinkers, web-based journalism promised that everyone, finally, would be let in on a conversation that had been too tightly moderated by journalists working at established organizations.

The internet was going to level the playing field and that would be good not only for citizens, but for journalists too and democracy itself.

One such voice was influential New York University journalism professor Jay Rosen.

But in December 2020, Rosen appeared on Twitter to issue a powerful mea culpa for “a big thing I got disastrously wrong.”

His error goes directly to why the ground beneath us now feels so flimsy.

It explains how internet culture deepens misunderstanding and mistrust of what journalists bring to the democratic discourse.

And his realization bodes well only for those who would profit from a war on reality.

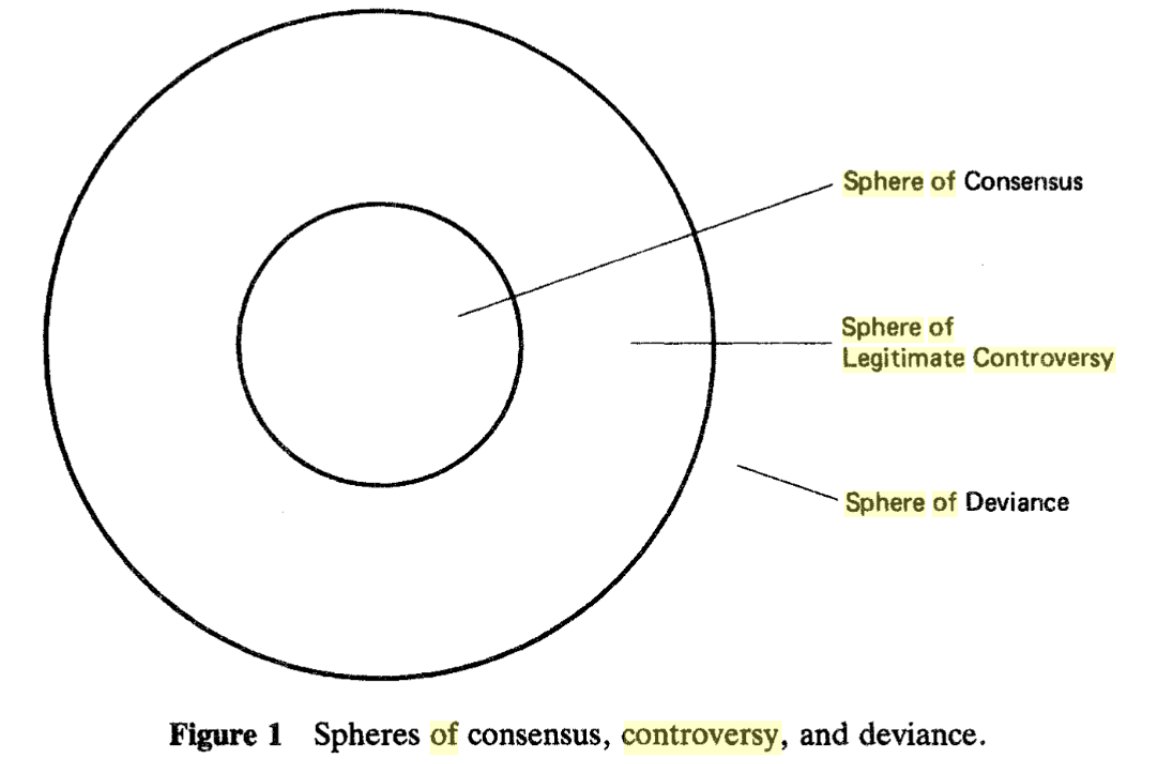

Rosen’s original 2009 essay was about this diagram, invented by a professor of communication named Daniel Hallin.

As Rosen explained:

“Hallin proposed that we think about the political influence of journalists by imagining three spheres: the sphere of consensus (core beliefs that make us one society)” — the hole in the doughnut — “of legitimate controversy (things we disagree on and argue about)” — the doughnut itself — “and of deviance (what is beyond the pale)” — outside the doughnut.

In this diagram, Rosen noted:

“The sphere of legitimate debate is familiar terrain for journalists. It is where most of their work takes place. In the sphere of deviance, says Hallin, are “political actors and views which journalists and the political mainstream of society reject as unworthy of being heard.”

So this doughnut is a diagram of contested spaces. As consensus about what is beyond the pale and what is worth discussing evolve, noted Rosen, “Things can move out of one sphere and into another."

I can see why Rosen saw potential in this diagram. All of us can think of issues we don’t think get nearly enough attention in the mainstream media, which means the social change we’d like to see is stymied.

Journalism itself could use a great deal more democratization, I agree.

That’s what Rosen thought when he noted:

“Hallin's model opened space for critique. Journalists are not only gatekeepers, but sphere-sorters. Part of their power is to police the boundaries between the spheres of deviance and legitimate debate.”

This caused frustration, Rosen said.

"These decisions are often invisible to the people making them, and so we cannot argue with those people. It’s like trying to complain to your kid’s teacher about the values the child is learning in school when the teacher insists that the school does not teach values."

But Rosen saw a new day coming, thanks largely to social media. He said:

Previously, "In the age of mass media, the press was able to define the sphere of legitimate debate with relative ease because the people on the receiving end were atomized.

And, equally important, they were without the tools needed to self-publish and share.

“But now we had the internet…. People were connected to each other AND to the media. They could pool their frustrations, criticize the calls journalists made, and make their own: what's in bounds, what's out.”

In 2009, Rosen celebrated what he called the “falling cost for like-minded people to locate each other, share information and realize their number.”

“Among the first things these like-minded people may do is establish that the 'sphere of legitimate debate' as defined by journalists doesn’t match up with their own definition."

But nine years later, Rosen was dismayed to see what he’d failed to predict. Now, he says, where we’ve arrived is frighteningly obvious:

“The falling cost for like-minded people to locate each other permits not only the criticism, but the utter rejection of journalism.”

He elaborates: “The falling cost for like-minded people to locate each other makes possible the mass delusion known as QAnon. It enables the Trump cult to detach itself from anything verifiable and spin off into resentment space.”

Rosen concludes:

“The falling cost for like-minded people to locate each other and share their truth is an integral part of a bewildering fact: today realism counsels us not to assign too much power to reality.”

The rise of social media has had another deeply damaging effect on the journalists who once played so large a role in mediating our doughnut of democratic discourse.

It has laid waste to the advertising model that largely paid their salaries.

Facebook’s riches are based on a simple proposition. Far better and more cheaply than old fashioned news media companies, it can deliver advertisements to receptive audiences that its own algorithms attract, sort and target.

It does so without the pesky need to employ journalists. Indeed it refuses to name itself a publisher, avoiding legal responsibility for the subject matter that flows to its 2 billion members.

Before social media, when I worked at the Vancouver Sun as an editor from 1998 to 2001, the newsroom was home to nearly 100 journalists. They were by and large very skilled and dedicated to the code of practice I described earlier in this talk.

Next door, the Province’s newsroom was just a bit smaller.

Today, I’m told by sources, their merged newsrooms number about 50 people and on any given day less than 10 of those are reporters available to dispatch on stories. That’s about the same number on staff at The Tyee.

The meteor that struck the Sun’s newsroom planet is the internet. When I was there in the late 1990s, advertising, not subscriptions, made up about 85 per cent of Sun and Province revenue.

The first internet shock wave was that ads online commanded but a tenth of the price of print ads.

But readers seemed destined to move online without any desire to pay offsetting higher subscriptions. So the Sun was slow to erect a paywall even as ad revenues dropped.

The next shockwave arrived in 2005 as Mark Zuckerberg’s Facebook joined Google to begin commandeering much of the news media’s online advertising.

As resources dwindled, the first to go was expensive journalism such as long-form in-depth investigations.

Fifteen years ago, most large and even mid-sized city papers in Canada had investigative units or at least afforded veteran journalists the time and legal support to do deep dives to hold power accountable. Those days appear all but over.

After years of regulators greenlighting consolidation by the big media owners, Canada has some big corporate brands who lean leftish or rightish. But they have been pleading poor for years.

Torstar, a major newspaper chain helmed by the Toronto Star, has shuttered many local papers in recent years. So has Postmedia, owner of the Vancouver Sun and Province and National Post.

Postmedia announced yet another round of layoffs in January — more than a tenth of its workforce.

Torstar, Postmedia and other large chains receive millions of dollars in labour subsidies from the federal government, ostensibly to help them eventually transition to internet sustainability — but their financial prospects continue to diminish.

The case can be made that years of media ownership concentration through mergers that pile up debt has placed much of Canadian journalism in a terribly precarious position.

In a recent piece published by the CBC, Patricia Elliott, a distinguished professor of investigative and community journalism at First Nations University of Canada, lays it out forcefully.

She writes:

“Last week's announcement of Postmedia staff cuts and property fire sales is but the latest outrage in a scenario foretold by decades of federal commission testimonials: if you allow our newspapers to fall into the hands of a few debt-ridden would-be tycoons fronting for foreign hedge funds, the failures will be catastrophic.”

She goes on:

“Canada's Competition Bureau has miserably failed to avoid this path, greenlighting monopolistic newspaper purchases against all public interest and common sense. Meanwhile, federal officials tasked with guarding Canadian ownership stood by as the fate of more than 100 Canadian newsrooms was handed off to foreign shareholders.”

Elliott reveals a disturbing truth that not many Canadians know, because we’re told there’s a logic driving regulatory decisions and government policies regarding our news media.

The primary goal, we’ve been told, is that Canada, in the shadow of the U.S. behemoth and global conglomerates, must maintain control of its news media. So do what’s necessary to prop up “our” news media.

Except, as Elliott writes, the true owner of Postmedia and thus “my local newspaper is Chatham Asset Management, a hedge fund in New Jersey.

“The second-largest shareholder, Allianz Global Investment, has offices from Shanghai to Frankfurt. Its main U.S. fund was shut down over securities fraud and ordered to pay back billions to bilked investors.

“The third-largest investor, Leon G. Cooperman, survived insider trading allegations by taking the Fifth Amendment in court and handing a $5-million settlement to the U.S. Securities Exchange Commission.

“I wonder how much of my local paper's revenues helps pay for such peccadillos.”

It’s a trend I’ve long tracked uneasily. In fact it’s why I was motivated to launch The Tyee as an experiment to see if the emerging internet could foster homegrown, locally controlled news organizations.

Small organizations where journalists could pursue the investigative and solutions-focused deep dives.

Local control seemed essential to me. Elliott says the same in her searing commentary. But she observes:

“Locally owned papers tend to do comparatively well in the media market. However, as demonstrated by the sorrowful history of media concentration, press barons will shutter newspapers rather than offer them to local buyers. At best, they'll sell the whole chain to another sprawling, indebted corporation.

“Sadly, we've reached a point where even if one link were broken off the chain, its physical assets will have been stripped and swallowed into the maw of CEO bonuses and company debt. All that's left to buy is a once-proud banner and a payroll liability,” concludes Elliott.

If grafting giant legacy media chains onto the internet hasn’t worked well in Canada, does that not leave open the potential for some tech savvy entrepreneur to start from scratch to build a sustainable journalism model?

And wouldn’t the most likely opportunity lie in local news, where the retrenchment of Big Media is leaving the market open?

Tomorrow, the wrap-up: Why foes of democracy wage war on shared reality. And why brave souls and bold policies are needed to address market failure in journalism. Read part two. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: