The encouraging news from India, in mid-May, is that case numbers are down — from a rolling seven-day average of 391,000 on May 9 to 354,000 on May 14. Meanwhile, about 4,000 Indians were dying daily during that week.

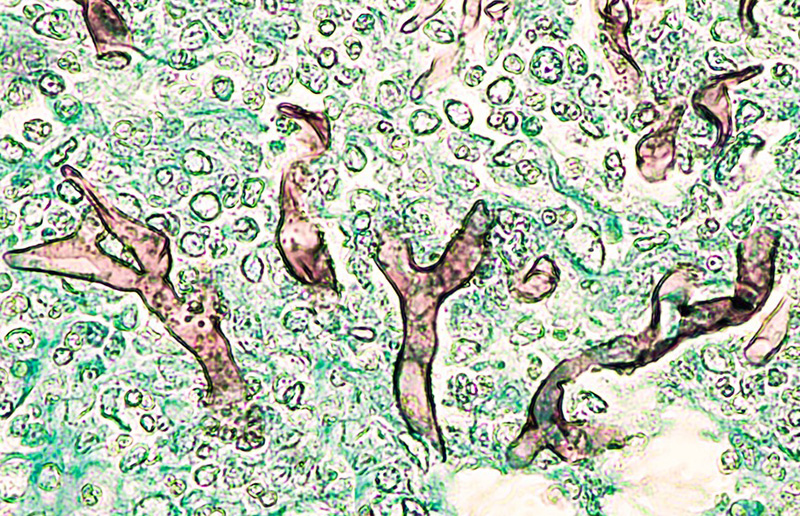

Now a new disease has arisen in India’s beleaguered hospitals, a disease attacking mostly those recovering or recovered from COVID-19: mucormycosis or “black fungus.” It’s putting a new stress on India’s crumbling health-care system — and it should remind Canadians that we face very similar threats.

Mucormycosis is a fungal disease, far more common in India than in the rest of the world. A 2017 survey of such diseases found that France sees about 4,200 murcomycosis cases a year while India sees 910,000. Another report found Canada diagnoses only 43 cases a year of black fungus out of 325,000 annual cases of fungal disease.

We’ll get back to those Canadian fungal cases, but first let’s look at what black fungus is doing in India. The fungal species that cause it are everywhere, often as a result of construction activity. When healthy people inhale or ingest black-fungus spores, their immune systems swing into action and demolish the invaders.

But just as COVID-19 flourishes best in populations that are poor, undernourished and stressed, black fungus preys on those with weakened immune systems or comorbidities like uncontrolled diabetes. Patients treated with steroids are also vulnerable to black fungus, and Indian hospitals have been using steroids heavily on their COVID-19 patients.

As one Indian doctor said: “Excess use of steroids and uncontrolled diabetes are the two major reasons behind the growth of black fungus. If steroids are used judiciously, glucose level won’t rise in a patient and therefore, there will be less chances of fungal growth. However, if steroids are used excessively, the possibility of fungal growth cannot be ruled out.”

The consequences of infection by black fungus are disastrous. Murcormycosis generally infects the jaw first, then migrates into the sinuses, nose and eyes, and eventually into the brain. At that point it becomes fatal. Patients feel feverish, with headaches and congestion; in the pulmonary version, they feel chest pain and shortness of breath. It can also infect the skin, creating blisters, and the gut, with abdominal pain and nausea.

Black fungus in India seems to be attacking patients’ faces, and anti-fungal medicines don’t always work. The only alternative is surgery, often the removal of an infected eye to keep the disease from reaching the brain.

Diabetics are easy targets for black fungus and other infections. In India, an estimated 77 million people have diabetes, almost nine per cent of the population. In Canada, about 3.7 million of us live with diabetes. That’s about 10 per cent of us.

But according to Diabetes Canada, Canadians most vulnerable to COVID-19 are also among those most at risk of diabetes:

- “Certain populations are at higher risk of developing Type 2 diabetes, such as those of African, Arab, Asian, Hispanic, Indigenous or South Asian descent, those who are older, have a lower level of income or education, are physically inactive or are living overweight or [with] obesity.

- The age-standardized prevalence rates for diabetes are 14.4 per cent among people of South Asian descent, 12.9 per cent among people of African descent, 9.4 per cent among people of Arab/West Asian descent, 8.2 per cent among people of East/Southeast Asian descent, and 4.5 per cent among people of Latin American descent.

- The prevalence of diabetes among South Asian and Black adults is 8.1 times and 6.6 times higher, respectively, then the prevalence among white adults.

- The age-standardized prevalence rates for diabetes are 17.2 per cent among First Nations individuals living on reserve, 10.3 per cent among First Nations individuals living off-reserve, and 7.3 per cent among Métis people, compared to 5 per cent in the general population. Further, the prevalence of diabetes among First Nations adults living off reserve and Métis adults is, respectively, 5.9 times and 3.1 times that of non-Indigenous adults.

- The prevalence of diabetes among adults in the lowest income groups is 4.9 times that of adults in the highest income group.

- Adults who have not completed high school have a diabetes prevalence 5.2 times that of adults with a university education.”

So if the Canadians most at risk of COVID-19 are also most at risk of diabetes, they are most at risk of opportunistic fungal infections if they’re lucky enough to have survived COVID-19. They may not contract murcomycosis, but a host of other fungi have been besieging Canadian hospitals for years.

Candida auris is a potential threat. First identified in Japan in 2009, it was found in 20 Canadian cases between 2012 and 2017, when the first multidrug-resistant case was reported — in a person who’d recently received health care in India. It’s not reportable in most provinces, so we don’t know how rapidly it’s spread. But it’s only one species of Candida; others are already well-established.

Fungal infections afflict about one in 50 Canadians: recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis, fungal asthma and bronchopulmonary aspergillosis are among them. About 3,000 Canadians suffer invasive fungal infections every year, and over half a million have a chronic Candida or Aspergillus infection.

Black fungus remains vanishingly rare in Canada. But many of us are vulnerable to fungal infections, which can travel the world just as COVID-19 has. For years our hospitals have tried to save money by sacking unionized cleaning staff and hiring cheaper, less capable workers. Hospitals have been battling local outbreaks of resistant infections ever since.

When health-care systems around the world have staggered under the shock of COVID-19, dealing with fungal and microbial infections only adds to their burdens. Many countries, including the U.S. and Canada, think the pandemic is almost over, and this will be the party summer that makes up for all the inconvenience since January 2020.

But if black fungus joins the other infections in our hospitals while we celebrate, we will see “excess mortality” among Canadians long after the COVID-19 pandemic is over. And they will be Indigenous, Black, South Asian and poorly educated, those who have already borne the brunt of this pandemic. If we don’t protect them, fungal infections will worsen the pandemic for all Canadians. ![]()

Read more: Health

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: