The hypocrisies of Let’s Talk Day have been well documented. Bell employees have come forward with horrifying stories about stressful work conditions, low pay and lack of benefits, and pressure on call centre staff to behave unethically to meet aggressive sales targets.

Many people who identify as experiencing mental illness openly dislike the campaign and find it superficial, unhelpful, even triggering.

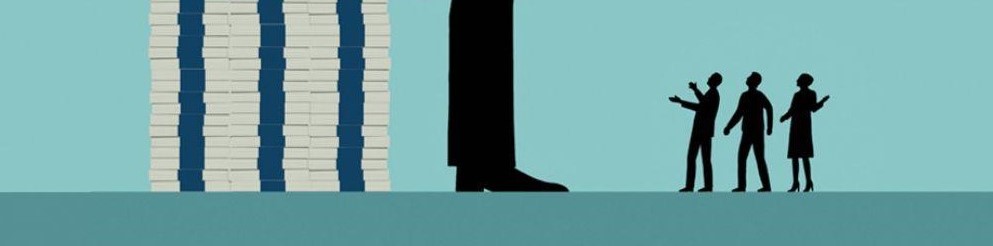

It is important to recognize that the main beneficiary of Let’s Talk is the corporation itself. True, Bell raises around $7 million per year for mental health initiatives through the campaign (while presumably receiving a charitable tax write-off). However, this is roughly $3 million less than the annual amount paid to George Cope, the company’s former CEO and one of the highest-paid executives in Canada before he was replaced by Mirko Bibic in January 2020.

In turn, Bell gets over 100 million interactions from their campaign and trends on Twitter in Canada each year. Since Cope founded Let’s Talk in 2010, Bell’s corporate profits have tripled to $3 billion per year and its stock price rose 37 per cent (the campaign may also have aided in Bell’s merger with Astral Media in 2013).

It would seem that Let’s Talk is little more than feel-good advertising for a telecommunications company accused of exploiting customers and contributing to Canadians having some of the most expensive cell phone bills in the world.

It is well known that inequality has been steadily increasing for the past four decades both within Canada and globally. So yes, let’s talk about mental health.

Let’s talk about how between three and five million Canadians live in poverty, while the nation’s billionaires collectively hoard over $150 billion.

Let’s talk about how the average worker in Canada earns roughly $56,000 per year, while top CEOs pocket over 175 times that amount, and millionaire bank executives whine about "bleak" bonuses.

Let’s talk about how it is in the interests of all those who hold disproportionate wealth and power in our capitalist economy to promote the idea that mental illness should be attributed to individual instead of societal factors, and therefore is best responded to with market-friendly individualist solutions such as psychiatric medication, apps, self-help books, consumptive self-care, or, if one is fortunate enough to afford it, therapy.

Let’s talk about all of this, because there is only one effective way for us to address the crisis of mental illness and addiction:

We must reverse the trend toward greater inequality by increasing taxes on corporations and the ultra-rich.

In The Inner Level, epidemiology professors Kate Pickett and Richard Wilkinson make a strong case for the damaging impacts of inequality on mental health, analyzing data from hundreds of studies from across the globe. They describe three typical responses to the status insecurity and multiple anxieties triggered by unequal societies. Some people become demoralized and depressed. Others become narcissistic and self-aggrandizing. And nearly everyone "becomes more likely to self-medicate with drugs and alcohol and falls prey to consumerism to improve their self-presentation."

Notably, they found that "although [inequality’s] severest effects are on those nearer the bottom of the social ladder, the vast majority are also affected to a lesser extent." Rates of mental illness are higher in societies with bigger income differences, with more unequal developed countries reporting up to three times the rate of mental illness than more equitable ones. Community life is weaker; people are less likely to be involved in local groups, voluntary organizations, and civic associations, and people are less likely to feel like they can trust each other and are less willing to help one another.

"Taken together, as of course they must be, both the quantitative and qualitative studies show how income inequality increases the strain on family life, and how things replace relationships and time spent together. The stories reinforce the statistics and vice versa. Parental experience of adversity is passed on to children through pathways that include parental mental distress, longer working hours, higher levels of debt and domestic conflict," the authors write.

There have been many criticisms of Western psychiatry and the "disease model" of mental illness from within the medical, psychological, and therapeutic communities. The rapidly growing field of epigenetics lends strong support to the idea that mental health struggles and addictions in adulthood are often a consequence of adverse childhood experiences. Our early experiences have profound impacts on our development and can change the expression of our genes. This particularly impacts the prefrontal cortex — the area of the brain most responsible for executive functioning, personality development, and social behaviours — which does not finish maturing in humans until their mid-twenties and thus is more susceptible to socioenvironmental influences.

The recent revision of the APA’s official diagnostic manual, the DSM, was particularly controversial. Prominent critics included Dr. Bessel van der Kolk, a leading trauma theorist and author of The Body Keeps the Score, who criticized the exclusion of developmental trauma, lamenting "psychiatry’s obtuse refusal to make connection between psychic suffering and social conditions," and Dr. Allen Frances, who had served as the chair of the task force for the fourth revision of the DSM.

In 2013, Frances published a book warning about the out-of-control "medicalization of ordinary life" and how the changes to the DSM feed pharmaceutical profits. Another interpretation of Frances’ claim here could be that people are being prescribed medication to help them cope with the increasingly stressful realities of late-stage free-market capitalism.

Quite simply, the more unequal a society, the higher the rates of stress, materialism, drug and alcohol abuse, dysfunctional and abusive relationships of all kinds, and the more likely children will be neglected during their critical years of development (in the United States, neglect is the most prevalent form of child maltreatment).

For the majority of families — who lack access to wealth and resources — child neglect is at least partially the result of lack of time, inadequate access to maternal care, lack of affordable counselling services for parents and children with addictions and/or mental illness, underfunded public education and community services, and lack of affordable daycare (our foster care system is cruel and unjust because it punishes parents for lacking the resources they need to care for their children, instead of helping them). In wealthy families, on the other hand, neglect and abuse is most often because of parental narcissism and workaholism. Even if a child’s physical needs are met and they are not being abused, emotional neglect can damage a child’s development and lead to attachment disorders and other mental health problems.

There are higher rates of school bullying in societies with greater inequality, and research on bullying has consistently found that many victims experience long-term adverse psychological effects well into adulthood. While bullies are found in all socioeconomic classes, victims disproportionately come from lower-income families. One can assume from the endless stream of articles coming primarily out of the U.S. about "toxic bosses," "toxic work environments," "toxic friends," and "toxic relationships" that these patterns continue into adulthood. In fact, Pickett and Wilkinson report that unequal societies damage well-being through toxic power relationships even if no one is living in poverty: "in terms of predicting mental distress, rank trumped absolute income."

A good example of the impact of status insecurity comes from Dr. Rhea Boyd of Harvard’s School of Public Heath. In January 2020, she published an article discussing a book by Jonathan Metzl called Dying of Whiteness: How the Politics of Racial Resentment Is Killing America’s Heartland, arguing — as summarized in a Twitter thread (Boyd has since locked her account) — that "Despair isn’t killing white Americans. The armed defense of structural whiteness is."

As I grew up in a wealthy household, I am ill-equipped to write on the adverse effects of poverty — I strongly encourage everyone to read work by writers, journalists, and academics from marginalized communities, in particular Black and Indigenous women, as everything discussed here is inextricable from the legacies of colonialism, slavery, imperial war, misogyny, and environmental destruction — and so I am going to shift focus here to the impact high inequality has on those who were born at (or clawed their way up to) the very top of the hierarchal ladder. This is because I believe that in order to achieve a better world, we would be wise to dispassionately study the behaviour of oppressors and listen to the experiences of the oppressed, instead of the other way around.

The relevant academic and policy question is not "Why do some people have so much less than others?" but rather "Why do some people insist on having so much more at the expense of other people?" One answer: Because some are narcissists in an economy that rewards narcissistic traits. "Narcissism is the sharp end of the struggle for social survival against self-doubt and a sense of inferiority," Pickett and Wilkinson write. "The connection between inequality and narcissism is supported by research on how growing up poor is associated with status-seeking and growing up wealthy with narcissism."

"Outward wealth is so often seen as if it was a measure of inner worth. And as greater inequality makes social position more visible, we come to judge each other more by status. With more social evaluation anxieties, problems of self-esteem, self-confidence and status insecurity become fraught."

Narcissistic people are more likely to hyper-competitively seek status, power, and wealth, and they are more likely to obtain it in our current economic system (just Google "narcissists" and "money"). Or as Nathan J. Robinson put it in Current Affairs: "This, for the most part, is what the extremely rich have in common: They are the ones who wanted money the most." These are the people who desire to dominate and control the world around them (while many cases of anxiety, depression, and demoralization can be attributed to a desire not to be subordinated, but also as characterizing a reluctance to harm others for personal gain). It is generally well accepted that many business leaders and investment bankers are psychopathic or narcissistic and a growing body of research supports this.

Children of psychologically abusive, narcissistic parents grow up into adults with chronic feelings of emptiness and are prone to self-destructive behaviours. On reddit, the "Raised by Narcissists" forum currently has over half a million members, who share stories of everything from being pitted against their siblings to financial abuse.

In addition, as Dr. Ramani Durvasula points out in her new book, a childhood characterized by the combination of emotional deprivation (as in neglect and abuse) and material overindulgence creates conditions for narcissism to flourish; people who have more opportunity to dominate and impress others are more likely to be rewarded for narcissistic traits. The narcissistic personality overlaps with the concept of "toxic masculinity" and research has found that "externalizing disorders, mania proneness, and narcissistic traits are related to heightened dominance motivation and behaviours." Tellingly, research suggests men are up to three or four times as likely to be narcissistic (the gap is widest for entitlement), while the majority of self-help books and articles on healing from narcissistic abuse are written by women.

Abuse, contempt, and victim blaming are typically directed down in hierarchies, while admiration, jealousy, and acquiescence is directed upward. Research in primatology, anthropology, and early childhood development indicates that human beings are wired for fairness; however there have always been people — usually young men — who desire to dominate and to have more than others. This has two important implications. Not only does inequality stress people out, but the more unequal a society, the greater the rationalizations as to why this is meritocratic or natural.

"The anthropological evidence suggests that equality in early human societies was maintained by what have been called 'counter dominance strategies': people who behaved in domineering ways were put in their place fairly systematically by being ignored, teased or ostracized, as others tried to maintain their autonomy," Pickett and Wilkinson explain.

In the abstract to Saving Normal, Dr. Allen Frances warns that "all of these newly invented conditions will worsen the cruel paradox of the mental health industry: those who desperately need psychiatric help are left shamefully neglected, while the "worried well" are given the bulk of the treatment, often at their own detriment." It is revealing that Bell’s "four pillars" toward "moving mental health forward" state that stigma is "one of the biggest hurdles for anyone suffering from mental illness," but does not say the same for the second pillar — care and access — which is a far bigger barrier for the many people with mental illness or addictions who are low-income or live in poverty.

A friend and business partner of former Bell CEO George Cope (who received the Order of Canada for Let’s Talk) described him this way: "I don’t know anyone more competitive than George — George really loves to win." Cope has reaped great personal prestige, power and wealth in a society that is organized to reward those obsessed with winning — and keeps raising the bar for victory.

Many of those winners are motivated by conflict, and some are willing to inflict intolerable amounts of stress upon the rest of the population with little to no remorse. It is time for what A.T. Kingsmith referred to a few weeks ago in this publication as "anxious solidarity," because unless we collaborate to stop them, these vampires will drain the world. Vampires are an oft-used metaphor for both narcissistic and rich people. The label is apt in cases where people are addicted to money, competition, and power; they will not stop hoarding on their own. As Robert Sapolsky says in his multidisciplinary tome, Behave, "Our frequent human tragedy is that the more we consume, the hungrier we get."

I’m not calling for a boycott of Bell or the Let’s Talk campaign, but rather for us to make good use of the platform they have so "generously" provided.

I think we can safely assume that most of us are aware of mental illnesses at this point, and so it is time to shift the conversation to how to enact meaningful change — and I suggest doing so using their hashtag, #BellLetsTalk.

We could share ideas for how Bell could improve the health of their employees (e.g. paying them better, or not firing them when they ask for mental-health leave.) We could suggest ways Bell could enhance the mental well-being of their customers by lowering the cost of cellular data, or maybe not exploiting prison inmates who wish to speak to their families.

We could explain how raising corporate taxes could fund a Green New Deal (as many suffer from climate despair), and social programs and public education reforms that provide support to families and improve the lives of all Canadians.

We could say how a universal basic income could lift millions out of poverty and empower workers to quit abusive workplaces and what David Graeber refers to as the "bullshit jobs" of capitalism, or how adding therapy and pharmacare to our health plan could be a lifesaver for hundreds of thousands of people who need but cannot afford help.

After all, talk is cheap. But, as this year’s slogan proclaims, "When it comes to mental health, every action counts."

Note: The author is not related to the founders of Bell Canada. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: