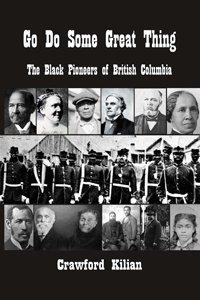

- Go Do Some Great Thing: The Black Pioneers of British Columbia, 2nd Ed.

- Commodore Books (2008)

[Editor's note: This is the last of three excerpts from the second edition of Crawford Kilian's Go Do Some Great Thing: The Black Pioneers of British Columbia, published in September by Commodore Books. The previous two told the story of the liberation of Charles Mitchell and profiled pioneer black women of B.C.]

Sometime in the mid-1860s, Wellington Moses arrived in the Cariboo. After wandering up and down the Fraser for a few years, he settled in Barkerville. Here he ran a sort of barbershop and dry-goods store, offering everything from ladies' shoes ("No more cold feet!" his ads promised) to his own renowned Hair Invigorator, which he advertised in both the Cariboo and the Victoria papers:

"TO PREVENT BALDNESS, restore hair that has fallen off or become thin, and to cure effectually Scurf or Dandruff. It will also relieve the Headache, and give the hair a darker and glossy color, and the free use of it will keep both the skin and hair in a healthy state. Ladies will find the Invigorator a great addition to toilet, both in consideration of the agreeable and delicate perfume, and the great facility it affords in dressing the hair. ... When used on children's heads, it lays the foundation for a good head of hair."

Although a single treatment cost $25 (about $320 in today's US dollars), he had a steady stream of customers for it, and some offered testimonials to its effectiveness in curing baldness.

Like most of the blacks in the gold country, Moses led a quiet, uneventful life. Most of his diary entries deal with the weather and his financial accounts, and little more. On one occasion, however, he helped to send a man to the gallows for murder.

Travelling companions

In the spring of 1866, Moses had travelled south to New Westminster, and on his return late in May he became the travelling companion of a young Bostonian named Charles Morgan Blessing. Leaving their steamer at Yale, the two men continued on foot toward Barkerville, about 400 miles north. (A stagecoach had been in operation since 1864, but was probably too expensive for the barber and the aspiring prospector.)

At Quesnelmouth they encountered another man, James Barry, who was also looking for company. Moses planned to break his journey for a few days; Blessing, however, was impatient to go on. As Moses later testified, Blessing was a timid man who distrusted most people, and he had reservations about Barry. He was carrying 50 or 60 dollars (about $650-$750 in today's money) -- not a large sum, given the cost of living in gold country, and he worried about being robbed.

Blessing's appearance may have made him seem more prosperous than he was: he sported an unusual tiepin, with a gold nugget naturally shaped like a man's profile.

Overcoming his fears, Blessing left with Barry after agreeing to meet Moses at Van Winkle, a mining camp on the road to Barkerville. When Moses reached Van Winkle, he found no sign of Blessing and went on to Barkerville. A few days later he met Barry in the street.

"What have you done with my chummy?" Moses asked.

"Who? Oh, that coon. [Since Blessing was white, it was an odd term for him.] I have not seen him since the morning we left the Mouth. I left him on the road. He could not travel; he had a sore foot."

The hurdie connection

Moses saw Barry twice more in following days, and each time asked about Blessing; the third time, Barry "looked savagely" at him, and muttered something under his breath.

One day in October, Moses was shaving a customer and noticed the man's tiepin. It was obviously Blessing's: a nugget with a man's profile.

"Where did you get that?" Moses asked.

"From a hurdie," the man replied. The hurdy-gurdy girls of the Cariboo dance halls were understandably popular in a country with few women. Moses in turn was popular with them, since he stocked ladies' clothing and perfume, and often lent the girls money. He soon found the hurdie, who told him James Barry had given her the pin some time ago.

Now alarmed and suspicious, Moses went to Judge Cox in nearby Richfield. By coincidence, a report had just come about the discovery of Blessing's body, not far from where he and Barry had last been seen together. Blessing had been shot once, in the back of the head, and his body had been concealed in some dense bush some 40 yards below the trail.

Pulled off the stage coach

As soon as news of the murder became public, Barry disappeared. On the strength of Moses's information, Judge Cox sent Constable John Sullivan out to track him down. Sullivan knew that Barry was surely heading south, and rode cross-country to try to intercept him at Soda Creek. He was too late: Barry had caught the stagecoach from Soda Creek to Yale.

Had he left a day or two earlier, Barry would almost surely have escaped, but as it happened the telegraph line from New Westminster had just been completed as far as Soda Creek. Sullivan sent the first message south, describing Barry to the authorities at Yale. When they took him off the stage, Barry gave a false name; undeceived, the local constable sent him back north.

As Sullivan took custody of the fugitive, Barry asked what he was charged with, and who had laid the charge. Sullivan replied that he would be told the details when they reached Richfield.

"It is the coloured man, Moses the barber," Barry said. "He was always asking me what had become of a man who had come up with me, and at last I got vexed and told him, 'I was no caretaker of that man.'"

Witness for the prosecution

Barry was jailed until the next assizes, in July 1867. Judge Begbie heard the case, including the testimony of Wellington Moses. He identified several personal items that had been found on Blessing's body, including a knife, watch, and pencil case. He also recalled that before leaving with Barry, the young man had said to Moses: "My name is Charles Morgan Blessing. Be sure to recollect it if anything should happen to me in this country." He had also mentioned having $50 or $60 left.

Other witnesses confirmed that Barry had been broke in Quesnelmouth but had been spending money in bars and on the hurdy-gurdy girls in Barkerville and Cameronton.

Though all the evidence was circumstantial, it was certainly enough to convict; the jury took only an hour to find Barry guilty. Next day, Begbie summoned the prisoner and asked if he had anything to say before sentence was passed. Barry began an incoherent story about leaving Blessing with a stranger while he himself went on with a party of Chinese. Then, as if realizing it was futile, he said: "This is all the statement I want to make." As Begbie concluded in his report of the trial, "Sentence of death was then passed in the usual way."

Barry's death warrant, with its official seal pressed into black wax, was issued on July 16. Three weeks later he was hanged at Richfield. Moses, meanwhile, had taken up a collection to give Charles Morgan Blessing a proper funeral in Quesnel and to put a headstone and railing on the young man's grave.

That grave is now British Columbia's smallest provincial historic site. As well, a memorial plaque to Blessing stands at Kilometer 43 on Highway 26 between Quesnel and Barkerville.