[Editor’s note: This article runs in a new section of The Tyee called ‘What Works: The Business of a Healthy Bioregion,’ where you’ll find profiles of people creating the low-carbon, sustainable economy we need from Alaska to California. Find out more about this project and its funders.]

What would you do with more than five million pounds of crab shells? Most people would turn their nose up, literally. This year, instead, Craig Kasberg and his company Tidal Vision will convert that massive pile into a product that, among its many uses, not only replaces synthetic chemicals but makes water cleaner.

Kasberg grew up walking the docks every summer in his hometown of Juneau, Alaska, where he would pester the local fishermen and beg them for a job. At age 14, he finally got a bite. “If your son still wants a job commercial fishing,” a boat owner bluntly told his parents, “I need to know in the next 24 hours, and we'll be leaving in 48 hours for a weekend.’”

Kasberg worked on commercial fishing vessels until his early 20s. After a year of college, he returned to the docks to embark on an entrepreneurial journey towards becoming CEO of Tidal Vision in Bellingham, Washington.

Founded in 2015, Tidal Vision has developed a unique way to process chitosan and sell it as a biodegradable alternative to toxic or synthetic chemicals in the agricultural, materials and water treatment industries. The polymer is derived from chitin, a building material naturally found in the shells of crustaceans, insects, algae and mushrooms. In the last quarter of 2023, Kasberg said his company’s 180 employees diverted a little over one million pounds of shells by making their liquid chitosan products, putting them on pace to hit 5.4 million pounds by this year’s end.

In 2022, crab was the highest valued catch in the U.S. at $584 million, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. But the meat-to-shell ratio for a Dungeness crab — the species most commonly used by Tidal Vision — is approximately one pound of crab meat to every three pounds of shell.

This leads to the between six to eight million tonnes of crustacean shell waste that’s generated every year by the global seafood industry. Most of that waste is either disposed of in landfills — for a pretty penny — or tossed back into the ocean. While it might sound sensible to send the byproduct back out to the ocean, a detached shell can reduce available oxygen, smother living organisms or spur excessive algae growth when it lands on the ocean floor.

This leaves seafood processors all along the coast searching for alternate means of disposal for the inevitable byproduct. At present, their options can be expensive.

In Oregon, seafood processors commonly send shells to dairy farms to be used as fertilizer or to pet food manufacturers to be used as an ingredient, according to Crystal Adams, executive director of the Oregon Dungeness Crab Commission.

“A lot of fisheries are very into sustainability,” she said.

Plus, both of those options are cheaper than sending the shells to landfill, Adams added.

While she doesn’t know the exact cost of shipping it to landfill, Adams said one of the facilities local to her pays about $400 per truckload of 18,000 pounds of waste to have it shipped to a field for use as fertilizer.

“And that's reused. So, I would imagine it would be that cost, plus the disposal costs,” she said. “It’s very expensive.”

From his years working in the field, Kasberg said he knows disposal fees can be steep and that’s why Tidal Vision pays local seafood processors 10 cents per pound to grind, dry and package excess Dungeness crab shells for them. If the processor doesn’t have the facilities to prepare the shells for them, Kasberg said they charge three to four cents per pound to pick up the shells from the source — which he claims is cheaper than having to pay landfill fees.

“Because our raw material is a byproduct we're diverting from landfills, and we have developed and scaled this low cost 'Chitofining' extraction process, we're displacing the synthetic chemicals at a lower cost with a better profit margin,” Kasberg said.

In her 27 years in the seafood industry, Adams said she began getting requests from businesses wanting shells for their chitosan 15 years ago — but she hasn’t seen much movement yet.

She thinks it’s a great idea, but said smell and cost of storage have been major deterrents to exporting shells for chitosan in places she’s worked.

“There's been a lot of requests for drying it out for the medical field, however, it’s costly and it smells, so you have to find a good area to do that. And then it just costs a lot to store it,” she said.

Often, she said the processor will ship the shells to another facility to dry them — which is where the smell complaints occur — but the logistics of storing the shells until they have enough to ship can be tricky because processing facilities are often tightly-packed.

But for the handful of seafood processors Tidal Vision is working with in Oregon and Washington, these obstacles don’t seem to be a problem.

From the local processors, bare, meatless shells travel to the outskirts of Bellingham where a dead end road leads them to Tidal Vision’s headquarters. On a windy day, the smell of pulverized crab shells — akin to fish food — wafts out of the tall garage-like doors pulled open to air out the place.

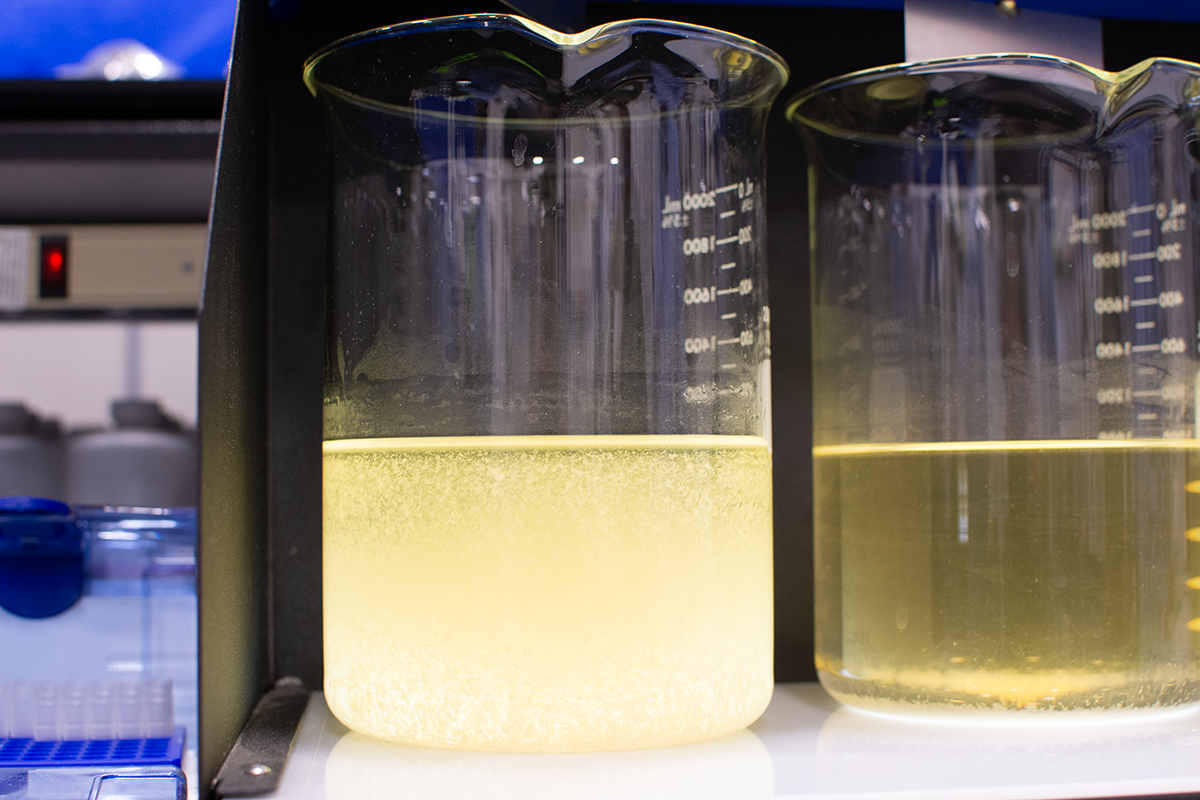

Brightly lit labs and board rooms with TV-like windows into the factory are sectioned off from the main space and compartmentalized on one side of the warehouse. Through their windows, huge vats and steel machinery can be seen spinning, churning and processing the company’s chitosan product while engineers and scientists scurry from one platform to another.

The Washington state-based company came to fruition because, as Kasberg explains it, a friend of his got fed up with his eagerness to discuss the overlooked shell extract and introduced him to the only other person he knew who would listen.

“A guy named John Foss who goes by ‘Johnny fishmonger’ says, ‘Craig, Zach is the only other person I've ever heard talk about chitosan, and neither one of you will shut the eff up about it. So you should really meet him,'” he recalled.

Zach Wilkinson became Kasberg’s entrepreneurial partner in crime, and together, they co-founded Tidal Vision and broke ground on a number of technologies that keep them leading the market today.

In the beginning, Kasberg said the pair used profits from a previous business venture to fund their research and development into chitosan extraction. Then, Tidal Vision opened its first pilot plant in a 20 foot shipping container where bioreactors with a capacity of 50 to 80 gallons were used for chitosan extraction.

Now, Tidal Vision works with bioreactors that have a capacity of 17,000 gallons.

Traditionally, the transformation of chitin to chitosan is done through a deacetylation process which involves treating chitin with sodium hydroxide or potassium hydroxide (also known as lye and potash) at an extremely high heat for several hours.

The issue with this method is it produces unwanted byproducts, like noxious vapours that can be dangerous for workers to inhale and polluted wastewater that can be costly to treat, according to Audrey Moores, a chemistry professor at McGill University.

At Tidal Vision, Kasberg and Wilkinson have found a more sustainable way to extract the biomolecule. Trademarked as "Chitofining," the process results in a liquid chitosan product, some sulphur and carbon dioxide emissions, and a sludge that’s repurposed as fertilizer.

The somewhat secretive technology used to do this was dreamt up by Kasberg and Wilkinson and assembled from “off-the-shelf industrial products designed for breweries,” as Tidal Vision’s creative director Alex Gaynor described it. Thus, making it easier to scale up, he added.

Moores, who specializes in researching the valorization of crustacean waste, said at the moment, there are three main methods she knows of to extract chitosan that aren’t the traditional deacetylation process.

They include using ionic liquids, enzymes and mechanochemistry, or solid-based chemistry.

At Tidal Vision, Kasberg said they extract chitosan using their “proprietary green chemistry combined with enzymes,” but the process isn’t solely enzymatic. Due to competition and the newness of their technology, the company was hesitant to share a detailed break-down of their process with The Tyee.

But once it’s in liquid form, the company’s chitosan product has a wide range of uses.

First, it can be used to treat wastewater. Industrial wastewater, specifically, is often contaminated by heavy metals, which treatment facilities use non-biodegradable petrochemical polymers to remove through coagulation. Similarly, chitosan can also flocculate or wrap itself around heavy metals, making a “solid you can filter out,” Moores explained.

“A lot of big industrial companies in water treatment have looked recently at replacing those ingredients with chitosan because it would be biodegradable,” Moores said.

So, if a spill occurred during the treatment process, or not all the solids were caught in the filter, the impacts of chitosan leaking out of a plant are much lower risk. Since it’s a naturally occurring molecule and not a persistent pollutant, there are enzymes in nature that can degrade it, Moores said.

Tidal Vision’s water treatment solutions — sold under the company’s Tidal Clear branch — are currently being used at more than 150 sites across the U.S., Kasberg said.

Recently, Kasberg said Tidal Vision even worked with the Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA, to have chitosan added to its Safer Chemical Ingredients List for water treatment — deeming it safer to use than “traditional chemical ingredients.”

Similarly, Tidal Vision has also petitioned the EPA to make its agricultural product easier to use. In 2022, the EPA added chitosan to its list of Active Ingredients Eligible for Minimum Risk Pesticide Exemption, following a petition submitted by Tidal Vision in 2018. It was the first substance to be added to the list in a decade.

The decision to make chitosan products no longer necessary to register under the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide and Rodenticide Act came after an opportunity for public comment and intense scrutiny by the EPA, Kasberg said. In the end, it concluded chitosan to be of “low toxicity to humans and no environmental risks of concern have been identified.”

“We're really excited that the regulatory bodies are recognizing the environmental and human safety benefits of what we're providing,” Kasberg said.

Being added to the list of minimum risk pesticides means Tidal Vision’s agricultural products don’t require an EPA label to be sold and are exempt from some otherwise cumbersome regulatory hurdles.

With its own website and CEO, Tidal Grow — the company’s agricultural division — is working on a slew of products that are all at different stages of development. Their shared purpose is to make the delivery of fertilizers and pesticides more efficient using chitosan.

Chitosan’s properties lend itself well to slow-release fertilizers, Moores said.

For example, Kasberg said Tidal Grow’s Spectra product triggers biological responses within plants that mean pesticides and fertilizers can be delivered in smaller quantities. Research shows this occurs because of chitosan’s symbiotic relationship with a bacteria found around plant roots that promote plant growth.

“The best analogy I've come up with, in layman's terms, is it's the difference of applying a drug topically to your skin versus injecting it into your vein,” Kasberg said.

“Chitosan is the only needle that enables that particular mode of action.”

In 2023, Kasberg said Tidal Grow products were used on more than 2.4 million acres of farmland, and he expects that number to almost double for 2024.

Tidal Vision’s third branch, Tidal Tec, deals with materials. Through partnerships with companies like Leigh Fibres — the biggest textile waste processor in North America — Tidal Vision has proven chitosan’s usefulness as a replacement for synthetic chemicals.

With Leigh Fibres, Tidal Vision provides an alternative to the halogenated flame retardants often used by the textile industry to treat fibres found in places like car doors.

“We were able to show that our chitosan-based, completely benign, green chemistry was just as effective in the standardized tests as the traditional halogenated flame retardants,” Kasberg said.

A number of startups working on biodegradable packaging solutions are also coming to Tidal Tec for their materials products. For example, Cruz Foam in California is using Tidal Vision’s chitosan as a key ingredient in its compostable and recyclable packaging.

Recent acquisitions and a plan to open a new facility in Texas in 2025 are among the markers of Tidal Vision’s success so far. And while the company grows, it’s evident there are few competitors working anywhere close to the scale at which Tidal Vision is operating, on the specific applications it’s targeting.

Gaynor said that’s partially because what the company is doing is, to put it plainly, difficult.

“It's really hard to do. You need to understand the process and you need a lot of expertise in chemistry, and at the moment, the way to make it is done in third world countries where there are less environmental registration requirements,” he said.

“So, designing a process that doesn't have waste and that you can accomplish in a western country took a lot of first steps.”

Moores said the market outside of North America is part of the reason why it’s difficult for companies working on more sustainable chitosan extraction methods to be successful.

“Right now, with the way it’s made in Asia, with its very cheap and dirty process, it’s a cheap commodity,” she said. “So, what (companies) are trying to do, is beat that.”

Beating that is exactly what Tidal Vision intends to do. With the company’s entire production process ready to be scaled up at a moment's notice, Gaynor said the company only has plans to grow. While there’s no shortage of crab shells for them to collect, he said there could be a future in which the company turns to shrimp next, and even possibly beyond seafood in the future.

“We intend to be the solution,” he said. ![]()

Read more: Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: