Change "Strait of Georgia" to "Salish Sea"? That’s a fine idea. But if this province is serious about changing place names born of its colonial past, then the first place to start is a spot in northern B.C. that signs tell us is "Squaw Lake."

It's long past time to end the continued use of the word "squaw" on government property.

For those who don't know, "squaw" is a bastardized pronunciation and spelling of the beautiful Algonquin word iskwew (pronounced es-kway-ew), which simply means woman. But somewhere along the way, as multilingual Turtle Island was forced to become mainly English-speaking, "squaw" became the ugly, common term used to refer to an Aboriginal woman, regardless of her indigenous heritage.

My own theory is that this word was adopted by the broader white society because it needed a word, many words, in fact, but one especially to sum up its contempt for Aboriginal women, and thus all Aboriginal peoples. And this word fit the bill, particularly since it made such a brutish sound when spoken.

While growing up in a farming community in the northeastern part of this province, I heard this word used pejoratively by Indian and Métis people alike, believe it or not. Years later I would learn that this type of behaviour was a form of internalized oppression, which is a product of colonization.

I also heard the word spoken by white people, which for me was always that much harsher to hear, especially when a white guy said it. As a boy I heard my own mother being cut down by this word thrown at her by two drunken white men.

Trigger of shame

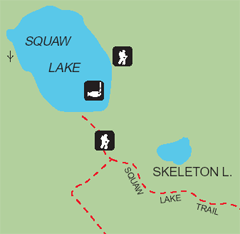

Crooked River Provincial Park is adjacent to Highway 97, about an hour's drive north of Prince George, and mere minutes from the hamlet community of Bear Lake. The park has a couple of lakes within its boundary. One of them, also called Bear Lake, is a good swimming lake, which makes it quite popular.

I first visited the park nine years ago with my then five-year-old daughter.

This is when I saw the park's signage with that word on it, which named the other lake in the park. This brought a flood of bad memories. I felt a sense of shame followed by an almost overwhelming compulsion to destroy those signs, right there, right then, and along with them that unholy word. But rather than lashing out like that or planning to deface the signs later, I instead convinced myself to take up the matter with the local parks office.

Soon after, I wrote a letter to a local parks official explaining that the word was offensive to Aboriginal people, especially women, and that it would be a good deed if he could take steps to change the lake's name in consultation with the local First Nation, along with the signs. I asked him not to view the issue as a matter of political correctness, but rather as a gesture of profound respect in light of one taking notice of another's offense.

I got no reply.

False promises

Frustrated, I took my concern to a prominent local First Nations leader. Together, we looked at other uses of the word as a geographical place name across the province. There were nearly 20. He brought this information forward to government with a request to remove the word from official use. Soon after, and coincidently enough, he was appointed a provincial cabinet minister.

In late 2000, the government announced it was removing the word from its official geographical place names registry. Good, I thought, believing then that the lake's name and those offensive signs would be gone in short order.

It should be acknowledged that the government's decision at the time was similar with an earlier one, whereby it relisted a species of trout then called Squawfish to Northern Pikeminnow. Moreover, these decisions were consistent with other North American jurisdictions, which were removing the word as a place name or a taxonomy term due to similar objections from Aboriginal peoples.

While in Prince George last year, I went to the park to see what the lake's new name might be. But instead of seeing a new name and signs, I was shocked to see that nothing had changed at all. Visitors were still exposed to "Squaw Lake." All of the original signs were there, except for one roadside marker that had been removed.

Strange logic, no consultation

Since then, I've been to the B.C. Parks website and found that the lake's name officially has been changed in 2006. But get this, to "Square Lake." The site doesn't indicate why this odd name was chosen. As it was, when government made its initial decision to remove the word from its place names registry, it said local Aboriginal groups would be consulted to find suitable replacement names, which I took to mean traditional names would be considered. But I doubt "square" is a translation of any local indigenous word.

In any event, the old signs and that word remain in use at the park. And on a map elsewhere on the B.C. Parks website the lake is still called Squaw Lake. Have a look for yourself.

My guess is that the new name – "Square" instead of "Squaw" -- was chosen because its spelling resembles the former, and then by some terrible leap of logic -- perhaps by that same local official who ignored me -- it was decided to keep the old signage, thereby saving the government the cost of replacing or modifying them.

Or maybe the signs remain because a local official wants to stick it to Aboriginal people for having rocked the boat in the first place.

Or just maybe there's a work order languishing on the desk of some mandarin who feels nothing has to be done about it because that person continues to harbour the old racist attitude of "it's only Indians." Who knows?

Signs of racism

It would have been a positive move for the local MLA to join with nearby native and non-native community people in a modest ceremony at the park, with a few humble words spoken on why changing the lake's name was important, along with unveiling new signage. But I suppose that would have been too much to hope for.

I say that because 10 years ago residents of Bear Lake adamantly protested against the prospect of a local First Nation selecting new reserve land alongside their community, as part of a treaty settlement with the province. In short, the residents said they didn't want Indians moving in next door. Rejected, the First Nation took up land elsewhere. That's the type of attitude that persists in parts of this province.

I cannot help but wonder how many park visitors over the years have seen those signs with that offensive reference on it. And I wonder how many, as a result of seeing that word in use, think it's acceptable to use it when referring to an Aboriginal woman. I mean, after all, there it is on full public display, adorned and sanctioned by the official symbols of the Province of British Columbia, no less.

Meanwhile, I recall that time when my mother was attacked with that dark, hurtful word. I remember how much it hurt me when it happened. At the time she refused to show her pain. She wanted to be strong. And she was. Eventually, though, I would learn how much this had wounded her.

For part two, go here.

Related Tyee stories:

- 'Getting Back Our Dignity'

BC's new lieutenant-governor on what Aboriginals want. - Campbell: 'No More Excuses'

BC Premier to Conservatives: reverse 'century of betrayal' in dealing with First Nations. - Reconciling with First Nations (series)

How the 'New Relationship' is faring in the Fraser Valley.

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: