Before restaurant ice machines and home refrigerators, ice was big business. In the early 1930s, Pennsylvania's York Ice Machinery Corporation produced 59 million tons of frozen water every year.

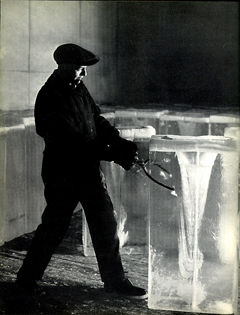

But as home refrigerators became smaller, cheaper and less smelly, the market for 400-pound chunks of ice shrank. The ice industry still exists, but the jobs that went with it in the '30s, like the one pictured above, changed or disappeared altogether.

The decline of North American manufacturing is well documented. And when people speak of lost jobs, they usually mean the same job moving somewhere else. But in many cases, actual types of work have disappeared from North America. From steel mill foremen to grunts in the block ice plants, jobs that were common 60 years ago have either vanished or changed so much as to be unrecognizable.

Thin vanities

The photographic proof of those jobs, and the workers who manned them, is remarkably thin, according to American visual artist Raymon Elozua. "Images of labour are very hard to find," Elozua told The Tyee. Factory owners and corporations, he said, were very cautious about how their workers were portrayed, and heavily controlled access to the jobsite.

As a result, what remains are "usually controlled images," Elozua said, "If [the photographers] had permission to go in, the photos would be heavily edited and looked over."

Workplace photos, where they do exist, were usually commissioned by the companies themselves. In corporate histories, self-published vanity books produced by companies before the age of the corporate report, Elozua found a wealth of images from the era of heavy manufacturing.

The photos that accompany this story are drawn from the more than 1200 vanity histories Elozua dug up over the past 25 years, starting in the late '70s. A larger selection is displayed in the online exhibit Lost Labor.

Originally, Elozua collected the histories for a book about the way the images were represented. In the vanity histories, the equipment, Elozua found, was usually valorized. The workers, where they appeared at all, were often there to put the machines in context.

Un-credited greatness

After other projects and copyright issues convinced him not to publish, Elozua came up with the idea of the Lost Labor website. "There are many layers to the title," Elozua said. Not only are the jobs displayed lost, but so too are the books themselves. Most of the photographs are un-credited, and Elozua believes many of the great American photographers of the 20th century contributed to them. "Industrial photography was a way of making money, it wasn't lionized," Elozua said. "It was really just a job."

Elozua picked up most of the books for virtually nothing at used bookstores across the U.S. Ironically, it was Japanese interest in American corporate history that drove up the market, so that many books now sell for upwards of $50.

And it is a university in Japan, or maybe Europe, where Elozua's collection will probably end up. After shopping them around to American institutions, Elozua is now resigned to selling the books overseas. "America is not that interested in history," he said. "We prefer not to think about the past."

Richard Warnica is a reporter in Edmonton and a regular Tyee contributor. ![]()

Read more: Photo Essays

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: