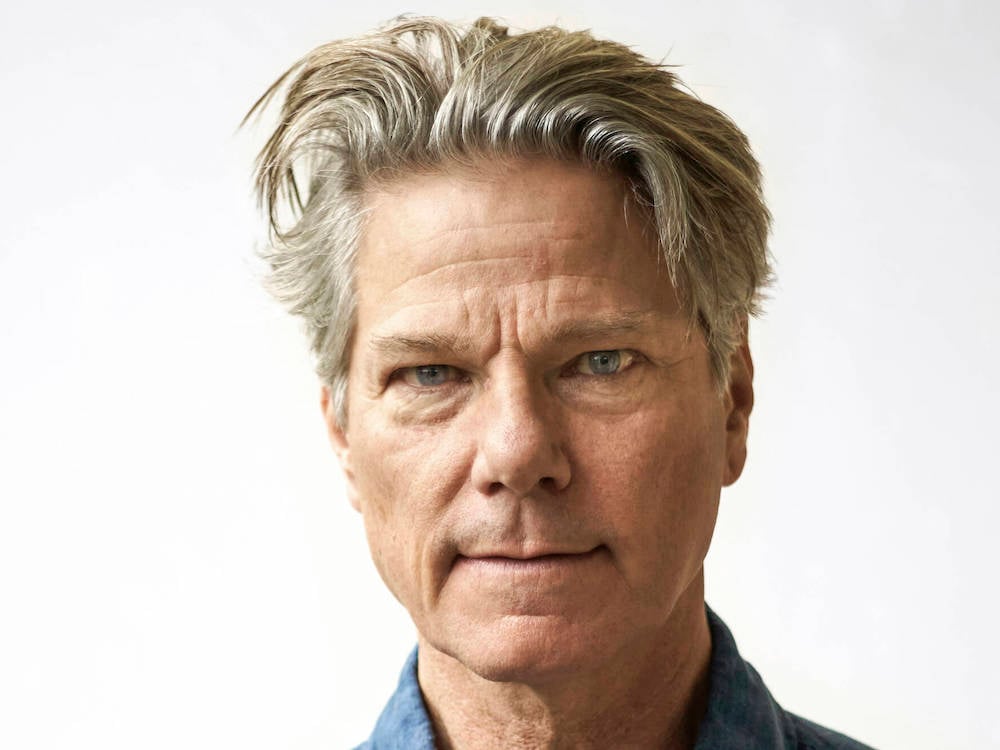

On Monday I was invited to be a witness at a special session with the House of Commons natural resources committee. The star was Richard Kruger, a veteran Exxon vice-president who emerged from retirement, along with his 1980s attitude, to become chief executive officer of Suncor.

Despite the fact that the hushed and peaceful halls of Parliament’s Wellington block have airport-grade security, Kruger arrived with his sunny and slender sustainability officer and two tough-looking bodyguards. The contrast to the rest of us was, well, noticeable. Hard to say if he felt the need to be protected, or the need to look intimidating.

Back in August, while Canada was burning from coast to coast, Kruger had made it clear that he’d be putting profits first, second and third. Never mind that Suncor had tripled its profits in a single year. Kruger predicted imminent layoffs of some 1,500 workers. And Suncor had decided to sell its renewable energy business, Kruger said, so that the company could focus on what they do best.

What they do best, let’s be clear, is squander untold billions of cubic feet of natural gas to melt bitumen out of a subarctic sand pile and pass it off as petroleum.

The committee, spearheaded by NDP MP Charlie Angus, is calling Kruger and Suncor on the carpet for “throwing into doubt their previously made commitments to reduce harmful greenhouse gas emissions,” a stance profoundly antithetical to the just energy transition we need as the climate crisis worsens.

In addition to Kruger and myself, others who testified on Monday included Charles Séguin, associate professor, Université du Québec à Montréal; Mark Cameron, vice-president for external relations, Pathways Alliance; and Adam Waterous, CEO, Waterous Energy Fund. Strange bedfellows is putting it mildly.

In his appearance before the committee, Kruger did not budge an inch from his previous statements, declaring the fossil fuel industry held no more responsibility for the “complex” issue of climate change than anyone else. Should you want to watch Monday’s entire special session, the video is available via ParlVU.

Suffice it to say that Richard Kruger and I are diametrically opposed in our views on how responsibility is distributed for the civilization-threatening crisis we face, and what we must do.

Below is the video recording of my opening statement to the committee:

And here is the text:

“I’m an independent journalist and author from Vancouver. My work is evidence-based and fact-based; there are about a thousand endnotes, footnotes and citations in this book. Fire Weather is currently a bestseller and a finalist for national prizes in three different countries. I think it’s because the topic — how our appetite for petroleum has supercharged the atmosphere, endangering us all — resonates with people, especially after this hellacious summer of CO2-driven heat and fire.

“Before I get into that, I want to say how honoured I am to be here. I come in good faith, as a proud Canadian who loves this country, and who is grateful for the extraordinary gifts petroleum has given us. Canada and the oil industry are about the same age, and we’ve both come a long way in a short time. So, unfortunately, has our climate.

“When Fort McMurray caught fire in May 2016, I was as shocked as anyone. Winter was barely over — local lakes were still frozen, and yet the temperature in northern Alberta hit 33 C. More disturbing was the relative humidity — 11 per cent. You know where 11 per cent humidity is normal? Death Valley. In July.

“When you transpose the climate of the hottest, driest place in North America to the Canadian boreal forest — a famously flammable ecosystem — otherworldly things are going to happen. And they did. Quick science lesson: radiant heat — the heat that tells you not to touch the candle flame — travels at the speed of light. On May 3, 2016, the radiant heat coming off the Fort McMurray fire — 10 kilometres wide with 100-metre tall flames — was 500 C. That’s hotter than Venus.

“That was Fort McMurray on May 3, and May 4, and day after day after day after that. That was also this summer in B.C., Alberta, Quebec and N.W.T.

“Firefighters in Fort Mac described houses burning to the basement in five minutes. I thought they were exaggerating; they weren’t. I talked to physicists: that’s what fire can do at 500 C. As a result, the firefighting operation became life-saving operations because there was no time to do anything else.

“What surprises everyone about 21st-century fire is how fast it moves. Talk to anyone in Slave Lake, or Fort Mac, or Kelowna, or Enterprise, N.W.T. There was a plume over there, and now I’m running for my life. This is happening because the hotter and drier the air and the forest, the faster and more explosive the fire.

“Climate science isn’t rocket science. By the 1770s, the greenhouse effect was understood in principle. By the 1850s, the heat-retaining characteristics of CO2 had been identified. In the 1890s, scientists were considering the possibility that industrial CO2 (from coal burning) could alter Earth’s climate. By the 1930s, evidence of warming was observed in global temperature records. In the 1950s, mass spectrometers could measure CO2 in parts per million (hence the Keeling curve).

“By the 1970s Exxon — Rich Kruger’s old company — was doing cutting-edge climate science. Internal memos reveal surgically accurate predictions regarding the relationship between increasing CO2 and the climate disruption we are now experiencing. Exxon knew, and so did Suncor.

“And then, in 1989, they turned their backs on their own science. They did it because they cared about the money more. They did it because they know the oil industry is, in essence, a fire industry — which means it’s a CO2 industry — which means it’s a climate-changing industry. This is basic chemistry and physics, and we cannot deny, or gaslight, or greenwash that fact away.

“To be clear, oil is a 19th-century fuel. The internal combustion engine was prototyped in 1860. Why on earth are we still using it? Two hundred thousand Canadians were driven from their homes by wildfires this summer. Tens of millions of North Americans were shrouded in toxic smoke. The Amazon River is drying up. If we don’t reduce emissions now, we’re going to make this planet uninhabitable.

“Canada’s leadership matters here. Our survival depends on it. Here’s the upside: when it comes to renewable energy potential, Canada really is a superpower. Right now, we are perfectly poised to embrace the greatest, greenest energy opportunity the world has ever known.

“So, who’s stopping us?” ![]()

Read more: Energy, Federal Politics, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: