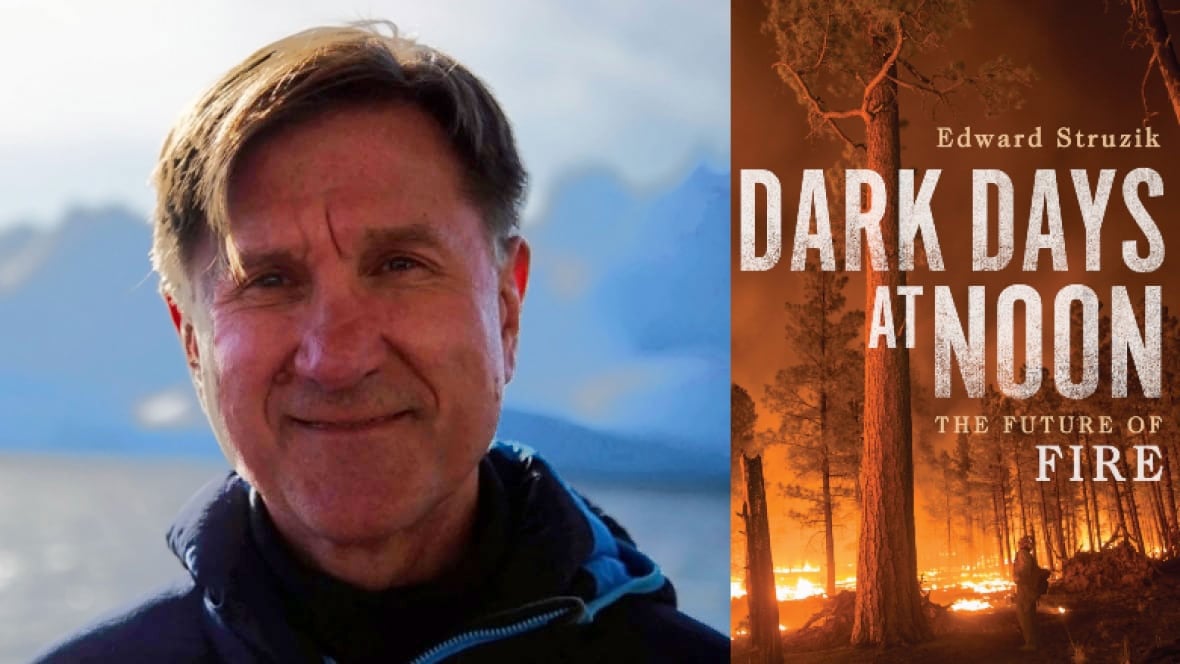

Ed Struzik, one of Canada’s preeminent writers about nature and policy, has dived into fire. It’s not a brand-new topic for him. Last year he wrote incisively in The Tyee about the changing character of wildfires, and he’s been called on to speak on the subject in places ranging from Whitehorse to the University of Trento in Italy. Now he’s published his eighth book, a sweeping must-read titled Dark Days at Noon: The Future of Fire, published by McGill-Queen's University Press. Tomorrow, we’ll publish a fascinating excerpt.

Today, we talk with Struzik about such topics as life before forest fire fighters, fire-driven storms and one particular conflagration that came to be called “the Holy Shit Fire.” The former Alberta newspaper and magazine reporter is now a writer and fellow at Queen's Institute for Energy and Environmental Policy at Queen's University, the 2022 Jarislowsky fellow at the University of Waterloo, and a regular contributor to Yale Environment 360, so we were lucky to grab some of his time. Here’s our exchange.

The Tyee: What got you so interested in wildfire?

Ed Struzik: Fires I experienced first-hand on many canoe and kayak trips in the Canadian North. My partners and I were never seriously threatened, but the glow of distant fires and the black pall of noxious smoke that spewed out from them were often surreal and very unsettling.

One conflagration that stands out was the one that tore through Kootenay National Park in 2003. There were bigger fires that year, including ones that drove 45,000 people out of the Okanagan, and 2,000 out of Crowsnest Pass in Alberta. Even polar bear dens burned on the west coast of Hudson Bay.

I got a chance to get up close to this one with firefighters from Parks Canada. It was a revelation.

They called it the “Holy Shit Fire” because every time an official got up in a helicopter to have a look, the response was always the same: “Holy Shit.” Only a handful of people know how close things came to the Banff side of Kootenay border lighting up. The forest there went on forever to the Banff town site. At times, the fire had its own mind, doing whatever it wanted to do. Fortunately, Parks Canada made the right decisions, even though some were not by the book.

I remember Rob Walker, the fire and vegetation specialist, telling me that this fire was a harbinger of future fires in a warming world. He was right, of course. But many people didn’t get it at the time. And still don’t.

There are several books on wildfire out there. What makes this one different?

I wanted to know why, after so many destructive fires have torn through places like Lytton, the Okanagan, Fort McMurray, California and Australia why we still don’t get it. I had a sense that it was cultural. And it is. Indigenous people have always got it. But policy-makers, artists, historians, farmers and homeowners didn’t for the longest time. Fire did not appear in history books until a decade or so ago. It was for the very longest time not a scientific discipline in universities. Even today, people refuse to believe that fire is a meteorological event, like a tornado or a hurricane, that can’t be stopped.

It's a little like British artists who refused to put fog in their paintings until J.M.W. Turner came along, or why media like The Tyee favour blue sky or partly cloudy sky photographs rather than rainy ones in the photographs they use. It rains on the West Coast doesn’t it? We treat the Arctic the same way. Leaden skies and fog that are common in the polar regions rarely show up in pictures.

OK, good point. We’ll run more rainy pictures here! Meantime, how did you come up with the name of your book?

I borrowed the title from a scientific paper that tried to unravel the mysterious origins of a fire in 1780 that so blackened the skies at noon from Maine to Massachusetts that settlers went to church firmly believing that it was a message from God and that the world was going to end. George Washington was baffled by it. So was the head of Harvard College.

In the book you spend a great deal of time and effort to point out that fires have burned big, hot, fast and with devastating impacts in the past. How bad was it?

A lot worse in many ways than it is today because there were no forest fire fighters on the ground in the 18th and 19th centuries, no early warning systems, and no real understanding of how fire behaved.

The carnage began in 1825 when Miramichi, the biggest fire in North America, killed at least 160 people and left thousands homeless. There were the Saguenay and Ottawa Valley fires in 1870 that forced the evacuations of several thousand people. Seventeen villages were levelled in Wisconsin the following year, killing between 1,200 and 1,500 people. In 1881, the toe of Michigan burned 1,480 barns, 1,521 houses and 51 schools, while killing 300 people and injuring many others. Part of Pennsylvania lit up at night that same year when fires overran 45 oil rigs as 15,000 men were fighting fires throughout the state and in neighbouring Ohio and New York. Smoke from those fires, and possibly those in Muskoka, may have produced a sky over Toronto that was of such “strange, weird glory” that the New York Times published an article describing people’s reactions.

The list is a long one. It just blows my mind that it was only two years ago that a book on Miramichi by historian Alan MacEachern was published.

What makes the present fire situation different from the ones in the past?

A warming climate, too many people living and working in harm’s way, and not enough of them burning lightly as Indigenous people once did. The boreal forest that dominates Canada was born to burn. Spruce and pine cannot regenerate efficiently without heat releasing seeds from their cones. We have also drained millions of hectares of wetlands that can slow or stop a fire.

You write a lot about Indigenous burning and how agencies like the national parks services on both sides of the border evicted Indigenous people from parks and protected areas — the topic of tomorrow’s Tyee excerpt from your book.

Indigenous fires reduced the amount of fuel on the ground for future fires to burn. With the end of this light burning and the strategy of full suppression that followed in and around 1910, we stacked up the woodpile, so to speak, to feed fire. Kicking Indigenous people out of national parks and protected areas because they burned lightly to regenerate grass for bison and young aspen for ungulates — there were other reasons — was unconscionable.

How do we get fire back on the landscape in a way that is beneficial rather than destructive?

We have to do more of the light burning that Indigenous people practiced. We also have to thin the forests that surround many communities in Canada. I would go as far as to suggest that cities such as Edmonton with urban forests that have not seen fire in more than a century, consider the idea before out-of-control fires come to them.

In one chapter you describe how fire-driven thunderstorms, or pyroCbs, and fire tornadoes are complicating the situation. Are these anomalies or are we likely to see more of that kind of extreme fire behaviour?

They used to be anomalies, or so we think. But then as the climate warmed and set the stage for bigger, hotter fires on the ground, pyroCbs became more common. The Horse River fire in 2016 spawned a pyroCb that ignited a cluster of fires more than 30 kilometres from the fire front on a blue-sky day. That was a head spinner until the following year when fires in British Columbia and Washington spawned five pyroCbs almost all at the same time. The smoke could be detected as far away as Greenland.

The biggest and most frightful pyroCb show occurred in the winter of 2019–20 when Australia suffered through its worst fire season ever. Eighteen pyroCbs erupted between Dec. 29 and Jan. 4. It was a meteorological show like nothing ever seen before — the kind you expect in over-the-top sci-fi films like The Day After Tomorrow, which depicted the rapid global cooling that takes place following the disruption of warm water circulation in the North Atlantic Ocean.

In the book, you write about nuclear winter, and how experimental wildfires gave scientists an idea what the world would look like in the event of nuclear war. Do runways wildfires have the potential to create a nuclear winter-like scenario?

The largest of the plumes in Australia in 2019–20 exhibited several previously undocumented phenomena. No other fire in history had sent so much smoke to heights of up to 16 kilometres. No other plume had exhibited such remarkable lofting. One plume rose from 15 kilometres to 30 kilometres. It was five kilometres thick and 1,000 kilometres wide. It travelled east from Australia to South America before reversing course in January and completely circling the globe westward over the next few weeks. Some of the smaller plumes were rising and rotating wildly.

Remarkably, the plumes shaded out the rays of the sun long enough to cool the global climate by about 0.06 C. According to the study that documented this cooling, it wasn’t so much the ash that caused it. It was the physical modification of the cloud cover that came with it. It’s not unlike a volcano erupting.

You spend a chapter evaluating the role of the media in shaping public policy.

Reading newspaper accounts of fire in the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries, I was struck by how well the wildfire issue was covered. The New York Times set the standard. The Illustrated London News really brought fire to life by hiring artists to depict fires in North America. Had there been an award for meritorious public service in journalism in 1922, as there would be later, the Globe would have won it. Following the Haileybury fire in northern Ontario that year, the paper ran dozens of articles, several editorials and opinion pieces on the subject of wildfire. The Daily Star was a close second. They really caught the attention of policy-makers. Things got done, albeit slowly and not always in the right ways.

It’s a different situation today. We do not have as many papers competing for readers. Coverage tends to be political. A minority of articles on wildfire make a connection to climate change. Few explicitly acknowledge that it is related to carbon emissions. Only now are we beginning to give Indigenous burning more credit. This has been a big miss and the reason why we are having such a difficult time dealing with fire.

Can we learn to live with fire?

We can. You can find out how by reading my book.

Spoken like an old pro who knows not to give everything away! We’re grateful for what you shared and encourage folks to buy the book. Thanks Ed.

Tomorrow: An excerpt from 'Dark Days at Noon: The Future of Fire,’ published with permission from McGill-Queen's University Press, chronicles the scapegoating of Indigenous peoples in North America by settlers for massive wildfires, and, over a century later, the return to Indigenous practices of controlled burns. ![]()

Read more: Media, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: