When sorrow billows like the sea, it can roll you over, just about anywhere. You’re going about your life, minding your own business when it swells and crashes. Last week it was in front of the jars of pickled herring at Trevor’s Independent.

Pickled herring, of all things. Dad’s favourite on toast on Sunday mornings. My sister and I would groan, mortified that he would end up at church smelling like fish. He would just grin and offer up his goatee for a sniff-test.

I’m 46 and it’s been over a year since he’s been gone and I would still give almost anything to kiss his face and feel his scratchy goatee. Even if it did smell of herring.

I know these memories won’t always make me sad. I know because that’s what happened after Mom died. But this time, with Dad, there is an undertow.

Regret drags me under the surface. Why did it take me nine months after his palliative cancer diagnosis to finally figure out a way to leave Yellowknife and go home to Toronto? Why did he have to die just 10 days after I finally made it there?

I loved my Dad. We had a close and special relationship. So why did I spend so much of my adult life so far away from him?

Stony paths

The herring-jar meltdown really bothers me. After a year away from Yellowknife, I thought I’d cried it all out already. I’ve cried a lot, pretty much every day through that fall after he died and well into spring when I left to walk the Camino de Santiago — an 800-kilometre journey through the French Pyrenees and northern Spain to Santiago de la Compostella.

Many people make that pilgrimage with a goal — a question to answer, a decision to make. For me, the walk was going to be a time to open up and just let the physicality of walking and the beauty of the place fill my mind. I would often walk alone in the mornings. Up and down stony paths, through eucalyptus forests, across yellow fields of canola. My pace steady, my feet blister-free, my body watered and fed, and my mind clear, I’d soak in the echo of the birds singing in a glade across the valley or fall under the spell of the spring wheat blowing in the wind. I’d feel happy for a moment or two. Then, just as quickly as it came, the feeling would be gone and I’d be crying my way along for a few kilometres.

I do realize this is how the circle of life works — best-case scenario, our parents die before us. Dad was 83. He was on his third round with prostate cancer. It was a terrible way to go, but, for him, better than the prospect that was already facing him: a slow decline into the useless body and demented mind of a Parkinson’s patient.

Then, on top of all that, he had a stroke. He spent three months in the hospital. He couldn’t do any of the things he loved: writing, reading, painting, or playing solitaire on his computer.

I remember helping make him comfortable in his bed the week before he died. He thanked me, and I told him I loved him. I waited by the side of the bed to see if he would settle. That’s when I heard him whisper to himself, three times, “I want to die.”

It wasn’t a complaint or even a plea. It was a demand he was making of God, an order he was giving his body. He was ready, so ready, to go.

But I wasn’t ready to let him go.

The decision

Six years ago I knew I had to make a decision, or regret would come calling some day. Dad had already been diagnosed with Parkinson’s. Medication was helping, but he’d developed all the hallmarks — stooped posture, expressionless face and shuffling, halting steps. Just as this was developing, I was finally settled into Yellowknife after more than a decade of rambling from Africa to Nunavut and now here.

I liked the kind of stories I could tell here. I had northern knowledge and experience. I liked being on the doorstep of the wilderness. I liked my community. After years working for CBC in Rankin Inlet and Iqaluit, my ability to drive my snowmobile to work was finally more in balance with the availability of a good latte. I had even saved enough money for a downpayment on a condo.

I wanted to be nearer to my father but I just couldn’t see myself living and working in Toronto, with the long commutes, the crowds, and the pollution. How does one even make new friends in a city that big?

I was also in love, and it seemed like things were serious. So I did the only sensible thing: I called my sister.

Ellen said a few things, but what stuck with me was that Dad wouldn’t want me to come home for him. Of course he’d be happy if I were closer, but if there was also a chance I’d be loved and have someone to love after he was gone, well that would make him happy.

So I made the decision to invest in Yellowknife and see what that future held but to spend as much time as possible with Dad when I would get time away from work.

The day I put in the offer on a condo, I called him.

“Well, it’s about time,” he said. “You are 40, you know. You should own a home and put down some roots at some point.”

Still, when I saw that pickled herring jar last week, the question pulled me under: Did I make the right decision? Was it really a decision at all, or was I just hedging my bets?

A prayer

The summer before I left for university in New Brunswick, my uncle took me aside at a family gathering. Wouldn’t it be better, he asked, if I went to university in Ontario? Shouldn’t I stay a bit closer to my dad, at least for now?

Mom had died that January. In the months afterwards, I had let my university applications sit on my desk — until it was almost too late. I kept busy studying, cleaning the house, doing laundry, making sure there was a hot meal every Sunday so we could invite “strays” home from church as Mom always did. It was when I started making Dad’s lunches that he finally drew the line. “It’s not your job to look after me or to do all the things Mom did,” he said. “It’s your job to enjoy your friends, finish school, and have a life of your own.”

So when I asked my dad about my uncle’s question, he looked at me and said, “God doesn’t give you children to bless yourself. He gives you children to raise into the kind of people that will be a blessing in the world.”

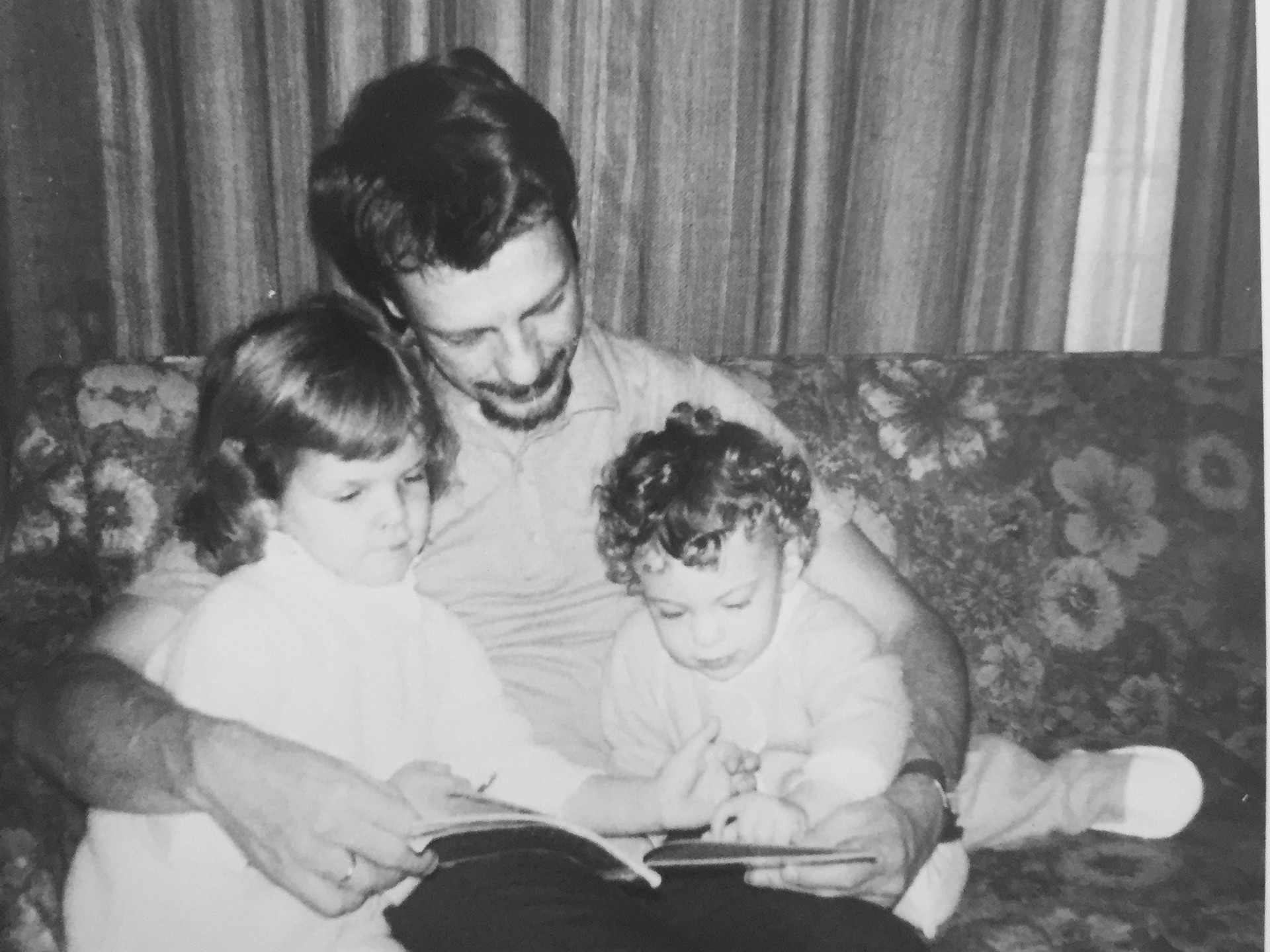

Dad had lived at home until he was in his mid ’30s. He told me many times he probably never would have met my mom if he’d continued living in his parents’ basement. So he was determined to raise his two daughters to be more independent than he was.

If it was his turn to help us dress, he’d let us struggle a bit to get into our clothes. “You have to let them do it for themselves, even if it takes longer,” he said, when I noticed him using the same technique with my oldest nephew.

As a teenager, I never really had a curfew but I would see his bedroom light suddenly switch off as soon as the car tires clanked over the sewer cover at the end of the driveway.

A few days before I left for three years in Uganda, I got a taste of the cost of living far from an aging parent. We’d been in a friend’s hot tub, talking about my trip and just before we got out, Dad said a prayer for me. A LONG one it turned out. When he got out of the hot water, into the cool air, he pretty much promptly keeled over. His first words at the hospital were, “I must be dying!”

After his blood pressure came back up he looked over at me and said, “I know what you’re thinking, but you’re still going to Africa.”

And so it was that I spent most of my adult life pretty far from my family. Sometimes a cousin or aunt would ask when I was moving home, and I would wonder. But not Dad.

The phone call

It’s 2014, the Tuesday after Thanksgiving. My boyfriend of four years gets in his truck and drives away from Yellowknife and out of my life. An hour later I get the phone call I was dreading. Dad’s prostate cancer has spread into his spine and pelvis. Somehow it still makes sense to me to go to work, so I back the car out of the garage and promptly smash the bumper against the doorframe. It’s when I see the gaping hole and the pieces on the ground that I start to cry.

I’m not in good enough shape to drive a car, let alone make a good decision that involves my career, my home, my finances. What isn’t helping is that Dad’s doctors are so unclear about his prognosis. His oncologist is hopeful he’ll have two years, but it could be nine months.

I’ve already used up my vacation to deal with some of Dad’s health crises. I ask about unpaid leave or a work accommodation in Toronto, so I can spend a month there and a month back here and still have an income. But there is a lot of change going on at work, and career-wise, it’s a terrible time to be asking for something like this.

Besides, how will I pay for flights and living expenses and still make the mortgage if I’m working part-time?

I discover more people have gone through this than I knew; people who have businesses here and kids in school. Some have partners who can carry the financial load for a bit. Others are single like me — with even less work stability. One friend, who put her business on hold when her dad was dying, offers me financial help, Aeroplan points, whatever she can do to assist.

One day as I’m waiting for a coffee at Javaroma, I run into a friend’s husband and somehow start spilling the whole story.

“What would your 21-year-old self do?” he asks.

It’s like the penny drops. It’s so clear. My 21-year-old self would go home to be with my dad.

At sea

Towards the end of my long walk through Spain, I found myself wishing I would have a dream about Dad. It had happened to me several times after Mom died, and she had always felt so real to me in those dreams.

This day, I walked past a gated garden and an old man came out with a basket of eggs over his arm and a tiny dog at his heels. We chatted in Spanish (very broken on my part) about the dog, the eggs, and about which ear was his good ear.

It’s not uncommon to run into a chatty older gentleman on the Camino. The usual farewell is, “Buen camino peregrina,” which means something like “Walk well, pilgrim.” This man, however, patted my arm, looked me in the eye, and said, “Vaya con Dios, hija.”

It isn’t until I walk a little further that my brain makes the actual translation: “Go with God, daughter.”

It’s not a magical encounter but it’s not a coincidence either. It’s really what Dad was always telling me.

I may never shed entirely this feeling I made the wrong decision, not taking the steps to move back to Ontario six years ago — and that I waited too long to go home when his cancer metastasized. I also know that because of my decision, I had some very special time with Dad. Two cruises to Alaska, a family vacation to Australia for my nephew’s wedding, long visits home where we would spend days just going for walks, or sitting and reading in the same room together.

On the first cruise, Dad wanted to go to the bar on the top deck. There was a live band playing blues and gospel music. It came as a bit of a surprise because Dad was no teetotaler, but he was definitely not a bar guy. I got him a gin and tonic, and he sat tapping his cane to the beat, a big grin on his face.

As we left the bar we were stopped by an older woman. She told us she’d been watching us over the past few days. “I can see the love you have for each other,” she said.

The reality is, you can’t entirely escape regret when someone you love dies. We all want more time or wish we’d said or done some things differently.

It’s not that I made a terrible decision six years ago. It’s that I’ve lost so much.

I’m learning to be thankful I will always have what that woman on the cruise saw between my dad and me. So when the undertow of regret tries to pull me under, I can swim hard and break the surface. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: