Almost 60 years ago, in 1957, I was in Mexico City staying with a Hollywood family in exile, part of a little community of blacklisted Americans. I mentioned to the father that this guy Fidel Castro seemed to be doing OK fighting a guerilla war in Cuba. (My chief news source in those ancient days was Time magazine, not the most left-friendly of American media.)

“They’ll never let him succeed,” the father said.

He had a point. In 1954, in this same house, I’d listened with the family to radio reports as the democratically elected Árbenz government in Guatemala was overthrown by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, launching half a century of genocidal violence against the Indigenous Maya. A few years in Latin America had taught us all why “Yanqui go home” was such a popular slogan. As a young gringo being chased down Mexican streets, I’d been in no position to explain that not all Yanquis were imperialist jerks.

Less than two years after that 1957 conversation, I was on the campus of Columbia University, waiting with thousands of others for Fidel Castro to arrive. On New Year’s Day 1959, Castro had chased the dictator Fulgencio Batista into exile and rolled into Havana with his army of “barbudos” — bearded ones — and not only American Reds were thrilled.

Before the 1960s had even arrived, Castro’s guys were late-60s cool. They had a raffish, bohemian charm in an age when a beard belonged only on Santa Claus. They were vaguely left-wing, but not just coffee-house radicals. These guys had guns and knew how to use them. Batista was just one of the many sons of bitches the U.S. had installed in Latin America to abort any move toward democracy, so Castro and his guys were a poke in the eye to the suits ruling Eisenhower’s America.

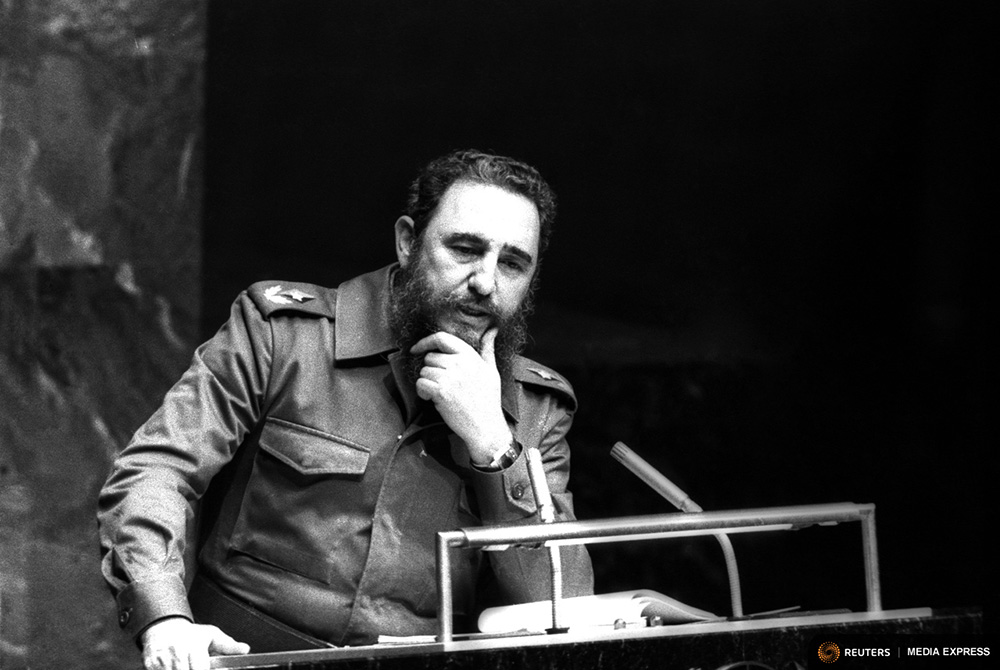

By the time Castro arrived in New York in 1959 to address the United Nations and do some interviews, the suits were already cooling to him. But when he arrived at Columbia that sunny spring day, the students who would be the next generation of suits cheered their heads off.

That was my first glimpse of charisma — a smiling, bearded man in olive-green fatigue uniform, waving from a distance and galvanizing thousands just with his presence. My second glimpse would be in Burnaby, when I watched Justin Trudeau stride into the local Liberal campaign office in the spring of 2015 and electrify a sweltering crowd of the party faithful.

Charisma in left-wing foreigners butters no parsnips for right-wing Americans, as Justin may soon learn — especially after his kind words the day after Castro’s death. The young Castro was soon in big trouble with both outgoing Dwight D. Eisenhower and incoming John F. Kennedy. Kennedy inherited a CIA plan to invade Cuba (hey, it worked in 1898!), and didn’t have the confidence to veto it. The idea of letting Castro just go ahead and build a socialist Cuba wasn’t even considered.

Support our SOBs

And the American suits had a point. They’d created an uneasy peace in Latin America and the rest of the world, built on supporting corrupt leaders as long as they suppressed their local left-wingers. President Franklin D. Roosevelt summed up the approach by supposedly saying of Nicaraguan dictator Anastasio Somoza “He may be a son of a bitch, but he’s our son of a bitch.”

It’s been the default policy of U.S. governments since the American conquest of the Philippines over a century ago. Eisenhower tolerated Papa Doc Duvalier in Haiti and Rafael Trujillo in the Dominican Republic. Richard Nixon overthrew Salvador Allende in Chile. Ronald Reagan invaded Grenada and launched state terror against Nicaragua, for those countries’ irresponsibility in trying to decide their own destiny.

The first President Bush took out the former pet S.O.B. Manuel Noriega of Panama when he outlived his usefulness, and Bill Clinton oversaw the discreet ouster of Haiti’s democratically elected president Jean-Bertrand Aristide. The second Bush would, less discreetly, remove former pet S.O.B. Saddam Hussein.

Kennedy was seriously embarrassed by the CIA’s screw-up in the botched Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961, and he looked like a lightweight to the Soviets. Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev triggered the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962 by shipping nuclear weapons into Cuba and stupidly imagining Kennedy would put up with them. After all, the Soviets had been putting up with U.S. nukes staring at them from Europe to Japan.

Shop till the bombs drop

You had to have been alive in the U.S. in October 1962 to know what the real sense of imminent nuclear war is like. I was living in Los Angeles then, and our local supermarket had empty shelves as panicked residents bought everything in sight before the Soviet bombers appeared overhead.

Castro, to his eternal discredit, was reportedly furious with Khrushchev for pulling the nuclear weapons out of Cuba (some of which had been aimed right at the U.S. navy base at Guantanamo).

That one terrifying month, however, taught the world a useful lesson. We have now gone more than 70 years without a nuclear war, and the Cold War ended (temporarily) with the fall of the U.S.S.R. and the seeming triumph of the West.

Castro survived the end of the Soviet bloc, as he survived all the CIA assassination attempts and state-terror attacks on his country. He played a few practical jokes on his enemies, like emptying his prisons of hard-core criminals in 1981 and allowing them to “escape” to the freedom of the U.S.

Most importantly, he survived to the great old age of 90, seeing off one American president after another. Dictatorship is not a job for the faint of heart, but it’s not a job for dummies either. Fidel Castro was a classic Latin American cacique, a macho Big Guy with a hairy face. He could have been a pet S.O.B. like the Somoza dynasty in Nicaragua, but the CIA would have taken him out as soon as he became inconvenient.

Instead he outsmarted and outlived the other S.O.B.s and the American suits as well, not to mention their commanders in chief. His political insights and skills were greater than theirs. He took power in 1959 in a country of six million, now 11 million, and for all his failures he showed Cuba could punch far above its weight.

Cuban troops fought against apartheid South Africa, in a war we should have fought. Cuban doctors, trained for free, spotted Haiti’s first cholera cases and kept the outbreak from being still worse. Other Cuban doctors are working across Latin America where no other health care is available. Cuba’s child mortality rate is lower than America’s.

Millions of young Cubans think their country is repressive, and it is. But if U.S.-sponsored governments had ruled them since 1959, most of those young Cubans would be illiterates (or dead), and their rulers would be sending death squads to deal with them if they got out of line.

In the eyes of the dictator-tolerant U.S., Castro’s real crime was failure to kowtow. That made him a dangerous example to other American client states, from Mexico to Chile. He showed you could make a poor country literate and healthy, even if not rich.

Yes, he suppressed his dissenters — just as the Americans routinely suppress dissenters all over the hemisphere. To the average poor Latin American, a good local school and medical clinic were worth it — plus the pleasure of seeing Fidel piss off the gringos for half a century.

Eventually Latin America’s governments have to make their peace with the U.S., and Cuba is no exception. But Fidel Castro’s long career showed them that they can make peace without a unilateral surrender. Now, with a Trump presidency just weeks away, that is a lesson they (and we) had better learn. ![]()

Read more: Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: