- Mark Twain and The Colonel: Samuel Clemens, Theodore Roosevelt, and the Arrival of a New Century

- Rowman & Littlefield (2012)

For most of the 20th century, its first decade was usually forgotten. Historians seemed to think that between Queen Victoria's death in 1901 and the start of World War I in 1914, nothing had really happened.

Now that we're in the same period of another century, we're looking at those prewar years with new interest. History, we're told, doesn't repeat itself, but it rhymes. If so, we are rhyming unpleasantly with the early 1900s. The early 20th century in America was a "Progressive" era, but a hundred years later America has made precious little progress from that grim and violent age.

Philip McFarland doesn't say that in so many words, but it's implicit in this sad, beautiful history built around the lives of two of the most famous Americans of their day. Samuel Langhorne Clemens, better known as Mark Twain, was a self-educated printer and journalist. Theodore Roosevelt was a Harvard-educated intellectual, descended from a long line of merchant-aristocrats. Both men were enormous successes, and disastrous failures.

Roosevelt, almost 25 years younger than Clemens, was one of his devoted fans, reading him aloud and laughing until he turned purple. Clemens, watching the political rise of Roosevelt, saw much to admire -- but then became his implacable enemy after the Spanish-American War and the U.S. takeover of the Philippines. Roosevelt, in turn, said privately that he'd like to "skin Mark Twain alive."

The two men embodied the American dream, each in his own way. Clemens rose from rural obscurity, going west to Nevada rather than fight for the South in the Civil War. He made no money in the silver mines, but his humorous and observant articles about the other get-rich-quick dreamers made him rich very quickly indeed. Exploiting his early success, he joined a group of rich Americans on a tour of the Holy Land; the result was The Innocents Abroad, the first of his best-sellers.

Frightening success

Clemens's success was so consistent that it scared him. One of his tour companions was a young man from a wealthy family. Clemens fell in love with a photo of his friend's sister, and married her. He set up his own publishing company, which brought out not only his own books but the memoirs of U.S. Grant -- an enormous success. Between his wife's wealth and his own, he was astoundingly rich and, by the end of the 19th century, arguably the most famous American in the world.

A high-tech visionary who wanted to become a great American capitalist, Clemens poured hundreds of thousands of dollars into a new typesetting technology that failed. Rather than go bankrupt and leave his creditors high and dry, he embarked with his family on a worldwide lecture tour that covered his debts and renewed his wealth.

But by the end of the century, Sam Clemens had suffered worse reversals: the death of an infant son, and then that of a brilliant and promising daughter who stayed home while the family went around the world. Then his beloved wife Olivia died after a long illness, leaving Clemens adrift.

His country seemed to be drifting as well. Clemens had lived as an expatriate through most of the 1890s, finding it cheaper to maintain his large household in Europe. Perhaps that gave him a detached view of his own country's growing strength. Clemens admired much of what the young president Roosevelt was doing, such as building up a powerful navy and sending it around the world.

He had also initially supported the Spanish-American War, which had lifted Roosevelt to national stature as leader of the Rough Riders in Cuba. The war was supposed to liberate Cuba, with the Philippines as a kind of afterthought. When it became clear that the Filipinos had merely exchanged colonial masters, Clemens became a strong anti-imperialist.

Attacking 'uniformed assassins'

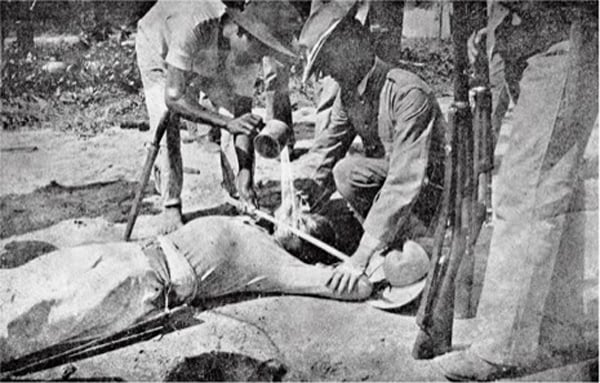

Here is where we rhyme with his era: Like Iraq, the "liberation" of the Philippines turned into an insurrection by the people to be liberated. Clemens furiously condemned his countrymen's war crimes, which included a form of torture he bitterly called the "water cure" -- we know it as waterboarding. "To make them confess -- what? Truth? Or lies? How can one know which it is they are telling? For under unendurable pain a man confesses anything that is required of him, true or false, and his evidence is worthless."

Clemens also condemned the 1906 Moro massacre, when 900 men, women and children were slaughtered by the troops of General Leonard Wood. He damned the general and his men as "uniformed assassins" and "Christian butchers," and sarcastically quoted Roosevelt’s letter of praise to Wood.

"In Clemens's view," says McFarland, "Roosevelt was insane about war anyway, and feats of arms, and the honor of the American flag no matter in what sordid way the 'honor' was upheld."

Coming from Sam Clemens, such criticism was vitriol. But the mood in the U.S. was already pro-war and pro-empire, and Clemens wrote several such polemics that he didn't publish, knowing they would hurt his reputation (and sales) if he published them. (The Moros, as Filipino Muslims were known, are still battling for their freedom.)

In his own way, Roosevelt too was a self-made man. He came from a wealthy family, but he had been a sickly, asthmatic little boy. As a youth he worked out, rode, hunted, and created the image of a man's man. Like Clemens, he wrote popular books on life in the west, where he bought and ran his own ranch. He was a formidable intellectual, energetically cranking out a naval history of the War of 1812, a multi-volume series of books on "The Winning of the West," and countless articles and speeches.

Like Clemens, Roosevelt was a husband who worshiped his wife. But when she died he almost never again mentioned her name and transferred his worship to his second wife. Both men romped with their children and basked in the attention of their large families.

Not a simple right-left conflict

Their conflict was not even a matter of right versus left. In many ways, Theodore Roosevelt was farther left than any president before or after him. He attacked the mega-corporations and the "malefactors of great wealth" who ran them. He was the first great conservationist and environmentalist, and an advocate for safe food and drugs. Yet he was also a racist, trained by his Harvard professors to believe in the superiority of the Anglo-Saxon over all other races.

Clemens meanwhile was friends with the likes of Andrew Carnegie and Standard Oil magnate Henry Huttleston Rogers, who put Clemens's finances on a sound footing after the collapse of his publishing house and his investments in the failed typesetting machine. And while he had grown up accepting slavery as natural, he outgrew the bigotry of his times and condemned it as "The United States of Lyncherdom."

Each man embodied one aspect of the American contradiction. One wanted to be rich, while seeing the folly in that ambition right from the start. The other wanted to be great, and saw the folly in that ambition all too late.

Roosevelt had fallen into the presidency after the assassination of William McKinley. He won re-election on his own, and promised he would not seek another term. His hand-picked successor, William Taft, was a disappointment, and Roosevelt went back into politics as leader of the Bull Moose Party in 1912. By splitting the Republicans, he handed victory to the Democrat Woodrow Wilson.

Wilson kept the U.S. out of World War I until 1917, when Roosevelt would have joined Britain and France years at the outset. War, he believed, made a nation "manly" and improved its character. When the U.S. did enter the war, Roosevelt offered to raise and lead a new American division like the Rough Riders. Wilson ignored him, but three of Roosevelt's sons did go into combat. Two were wounded in action. And Quentin Roosevelt was shot down in a July 1918 dogfight.

"Roosevelt never recovered from Quentin's death," McFarland writes, "although he bore it stoically... Yet privately, alone, the father felt the loss of poor Quinikens to his core, and to the very last." He died in his sleep in early 1919, a few weeks after the Armistice.

From success to disaster

Both men had become symbols of American success, and had pursued that success into disaster. Each man stood for an America that rebuked the other. Yet each retained a profound respect for the other. When Clemens came home to the U.S. after his wife's death in Europe, Roosevelt ordered the customs office to admit the widowed author's luggage without inspection. And Clemens never again spoke a critical word in public about the first imperial president.

Philip McFarland observes, late in his book, "The humorist could never have foreseen -- though he seems sometimes to have intuited -- the America of our own day. Back then nobody could have: the more than 800 permanent United States military bases set up in foreign countries on every continent but Antarctica, not counting bases at present (2012) in Afghanistan and (still) in Iraq;... and the chief executive himself invested with swelling imperial powers assumed on the all but unchallengeable grounds of national security... Even his own times, at the outset of our progress toward policing the globe, was proving too much for the humorist.

"'The 20th century is a stranger to me,' he wrote in his notebook. 'I wish it well but my heart is all for my own century. I took 65 years of it... just on a risk, but if I had known as much about it as I know now I would have taken the whole of it.'"

The 19th century as we know it was largely created by Samuel Clemens. The 20th century, and our own 21st, were largely created by Theodore Roosevelt. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: