"From and after the passing of this Act the inhabitants of the tract of land hereinafter described in the second section hereof, and their successors shall be, and are hereby declared to be, a body politic and corporate in fact and in law, by the name of 'The City of Vancouver.'"

On April 6, 1886, B.C. lieutenant-governor Clement Francis Cornwall signed the Vancouver Incorporation Act, with the stroke of a pen transforming a rough-and-tumble logging village into a bustling port city. It's a date often honoured with lavish civic celebrations embracing the now-familiar narrative of Vancouver's seamless transition from Milltown to Metropolis.

But Vancouver's birth was far less wholesome than the tourist brochures might suggest. The city was created thanks to land-grabs, cronyism, property speculation and corporate pressure -- much of it from the largest company of the day, the Canadian Pacific Railway.

"No question, [the CPR] were the major corporate influence on the development of Vancouver," notes historian Daniel Francis. "It had members on city council -- at any one time, there was somebody who was at least loosely connected to the CPR, to make sure its interests were looked after," he says. "In the history of the city, decade by decade, one finds its pervasive influence continues -- usually related to real estate, but that's always what Vancouver's been about."

There's no question today's city policy is guided by commercial interests -- in Vancouver's case, primarily real estate developers, who have spent decades contributing to municipal political parties.

But that's nothing new. Corporate meddling produced the city's name, its layout, its streets and even its very existence. From the time the CPR was created in 1881, Port Moody had been the planned location of the western terminus of the rail line, which would have brought incredible economic prosperity to the community.

But when a CPR delegation that included general manager William Van Horne arrived to inspect the proposed site in August 1884, they were unimpressed and promptly sent surveyor Arthur Wellington Ross to inspect the dense wilderness near Coal Harbour. Oblivious to CPR's changing plans, Port Moody welcomed the delegation with a lavish party. Streets were draped with banners and the Elgin House Hotel decorated with wreaths of flowers.

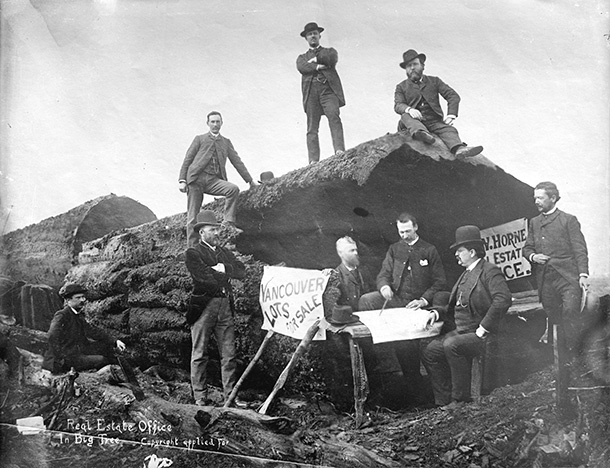

The railway's changed plans crushed the hopes of those hoping to cash in on a Port Moody boom. Real estate ventures collapsed and many investors lost their shirts. "Speculators had bought up all the land around there," notes author Donald Gutstein, "but the CPR outfoxed them and moved the terminus to Vancouver. And they made sure they owned most of the land around it. They had quite a large land grant -- a significant portion of land in downtown Vancouver was given to the CPR."

In total, the railway acquired a staggering 6,458 acres in government land and 175 acres from private citizens in what would become Vancouver. CPR affiliates and their friends, having quietly bought up all the available land near the new terminus, made a fortune. And the railway set about grooming the region surrounding Coal Harbour into "Canada's Gateway to the Pacific." Only one obstacle remained: there wasn't a city there. At least, not yet.

Muddy, reeking streets become a real estate score

Before 1886, Vancouver (then known as the Townsite of Granville) was the Wild West, with a lumber mill and a few crude shacks surrounded by dense forest and blackberry bushes. Roughly half the buildings were bars, all open 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Most of its approximately 250 inhabitants were men, and the single Dominion Police Force constable had his hands full dealing with street brawls and public drunkenness.

"You remember the HBO series 'Deadwood'?" Francis asks. "Early Granville always makes me think of that: muddy streets, stumps in the middle of the street, it probably reeked of garbage and excrement all the time. Smoke all the time from the clearing fires. It would not have been a pleasant place to live."

But on Jan. 8, 1886, a public meeting was held to change all that. Following a speech by MLA and provincial secretary John Robson, a committee was assembled to petition the B.C. government to officially incorporate the townsite. The committee included six longtime Granville residents and three agents of the railroad.

Robson's overlapping roles illustrate the murky boundaries between the CPR, government and private landowners. In addition to being provincial secretary, he owned the New Westminster British Columbian, a newspaper that had publicized the meeting, and often wrote eloquently in support of incorporation.

And while Robson regularly denounced the evils of land speculation (on one occasion, he derided speculators as "soil-grabbers"), he had few qualms about engaging in the practice himself; the sale of his land near the Coal Harbour terminus (bought with insider knowledge) netted him a fortune. By 1892, he was described in a letter by Liberal MLA John Grant as "the most successful land speculator in the province." Robson's critics had long accused him of being in the CPR's pocket, and in fact he did much of the work in convincing Granville's private landowners to give up their property. (By the end of his career, he had helped the CPR appropriate more than six million acres.)

The idea of "conflict of interest" didn't seem to exist, Francis says. "When Col. [Richard Clement] Moody and the original surveyors set aside the reserves for Granville townsite and Stanley Park, Moody immediately snapped up a lot of that land, and then shared it with his friends. The business elite was very tied into the political elite."

Gutstein agrees that most of the overlapping roles weren't really seen as a conflict. "Today, you'd consider it one because we don't think of city government's role as being primarily to aid developers. They've got obligations to citizens and communities," he notes. "But back then, only property owners had the vote, and what was good for one property owner was generally good for all property owners."

Pervasive railroad influence, even on the name

Of course, Robson wasn't the only one making a killing in real estate. Most high-ranking railroad employees and associates were doing the same thing, including Ross (also an MP) and CPR land commissioner L.A. Hamilton.

Hamilton laid out Vancouver's first street system, naming many of the downtown thoroughfares after prominent friends in the CPR, including Robson, H.J. Cambie, and even himself. ("I cannot say that I am proud of the original planning of Vancouver," he later wrote. "The work, however, was beset with many difficulties.")

Armed with a land grant that included much of the downtown peninsula, the railway set about turning urban growth away from the private land in what is now Strathcona and Gastown, creating both the West End and an east-west divide that persists today.

Railroad influence didn't end there. It even extended to the new city's name.

"The name was the choice of Sir William Van Horne," explained Hastings Mill manager R.H. Alexander, in a 1911 speech. "When the question first arose, the old residents naturally thought the old name [Granville] good enough, but Sir William used all his influence with us for the name Vancouver."

The choice was met with little enthusiasm in the legislature. At the time, George Vancouver's reputation was none too strong (he'd died, penniless and forgotten, in 1798). And many worried that the city would be confused with Vancouver Island.

"I did not suppose anyone would say the selected name had been a wise one," griped Cassiar MLA Grant, going on to call it "injudicious."

Kootenay MLA R.L. Galbraith was later even more critical. "The selection of the present name was not a matter of local option at all, but was forced on the citizens of that place by an agent of the CPR," he complained.

But Van Horne was undeterred. "All through he stuck firmly to the name," the CPR's Hamilton wrote in a letter to city archivist J.S. Matthews, "even when parliament at Victoria discussed the inadvisability of calling the terminus by that name, and showed their opposition to it."

As the city grew, real estate money and corporate interests continued to guide its progress. Many of the first mayors, including Malcolm MacLean (who was also Hamilton's brother-in-law) and David Oppenheimer, were in real estate.

And the CPR continued to be hugely powerful. The railway company lobbied for the present location of City Hall and for the creation of Stanley Park -- in both cases to increase its own land values. As the company extended its rail line west, it evicted city pioneer Sam Greer from his own property near Kits Beach. The CPR built the city's first opera house, as well as the first and second Hotel Vancouver. Yaletown was named for the home city of nostalgic CPR clearing crews. Vancouver's oldest elementary school (and subsequently the neighbourhood surrounding it) was named for Lord Strathcona, who drove the last spike at Craigellachie. Marathon Realty, the company's real estate arm until it was sold in 1996, was a significant presence through the 1970s and 1980s, and at one point employed a young Gordon Campbell.

In recent decades, however, railroad influence has been on the decline, and with the recent sale of the Arbutus rail corridor the last major symbol of CPR dominance is set to disappear.

Yet subtle reminders of that early influence will remain around every corner: Stanley Park, the West End, the street system, City Hall, Yaletown, the Roundhouse Community Centre, all mementoes of the city's corporate beginnings and the nepotism, cronyism and backroom land deals that made Vancouver what it is today. ![]()

Read more: Local Economy, BC Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: