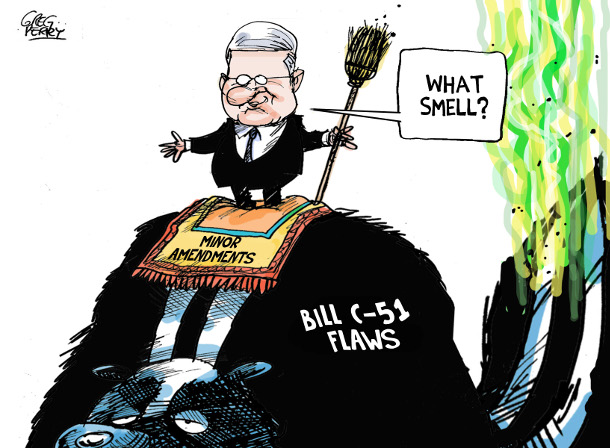

Bill C-51, the Harper government's proposed anti-terrorism law, was considered in clause-by-clause detail at the House of Commons Public Safety Committee on Tuesday. With a great deal of advance fanfare, the government trumpeted that it would introduce amendments, supposedly showing that it had listened to critics. There were four government amendments, all accepted; all opposition amendments were rejected.

Do the government amendments change anything? Two of the changes eliminated loose phrases that were probably always throwaway lines. Another removes "lawful" from "advocacy, protest and dissent." This is an improvement, but is unlikely to mean a great deal in practice.

However, it was the fourth amendment that had observers scratching their heads. The section of the bill that would confer open-ended powers on the Canadian Security Intelligence Service to "reduce" terrorist threats will now bear a new clause: "For greater certainty, nothing in subsection (1) confers on the Service [CSIS] any law enforcement power." Government spokespersons helpfully explained that this meant CSIS could not "arrest" anyone.

This is the proverbial solution in search of a problem. Of course CSIS can't arrest anyone. Never could. CSIS is a security intelligence agency tasked with collecting and assessing information on threats to the security of Canada. At least it was until Bill C-51, which will confer so-called "kinetic" powers on CSIS to take actions in the real world, disruptive actions that could even break the law and violate Charter rights -- with prior judicial authorization. But that's all right, the government was saying, because CSIS can't "enforce the law" by "arresting" anyone. This is the old bait and switch trick. Critics worry that CSIS could break the law. The government says no problem: CSIS can't enforce the law.

Allow CSIS to detain?

In adding this superfluous clarification could the government have had something else in mind? Might it be seeking to divert critics from another potential controversy hidden in Bill C-51? In stressing that CSIS can't arrest people, might it be trying to deflect attention from a brand new capacity of CSIS to detain people?

"Arrest" is a term of art. A person is arrested on a specific criminal charge to be heard in court, with habeas corpus and legal representation. "Detention" is an extraordinary power, outside the normal law enforcement process, which may or may not bear the same safeguards as arrest. Under the old War Measures Act (now repealed) the Canadian government, in both the Gouzenko spy affair of 1945 and the 1970 October Crisis in Quebec invoked national security to detain and interrogate people without criminal charges and without legal counsel. In both cases, these instances were controversial as departures from the rule of law. When the Chrétien Liberal government introduced a new power of preventive detention in its Anti-terrorism Act 2001, it proved sufficiently contentious that a sunset clause was added. After five years, Parliament had to renew the power or it would lapse -- which was exactly what happened in a minority Parliament with the Liberals and NDP voting against renewal. Subsequently, the Harper government restored the act after it won a majority in 2011.

A strengthened version of preventive detention reappears in Bill C-51, extending initial detention from three to seven days and lowering the threshold from "will" to "may" commit a terrorist offence. This preventive detention power has not drawn a lot of criticism, and indeed may be the least controversial change in Bill C-51. After all, full legal representation is available to a detainee, and any extension would have to be brought before a court. Anyway, preventive detention has never actually been used.

More alarming is another possibility lying hidden in plain sight in Bill C-51.

The bill also gives new and greater powers to CSIS: "If there are reasonable grounds to believe that a particular activity constitutes a threat to the security of Canada, the Service may take measures, within or outside Canada, to reduce the threat." Just what such "measures" might include is not specified. In pursuing such measures within Canada, CSIS is empowered to break Canadian laws and violate Charter rights of Canadians if they have obtained a warrant (the so-called "disruption" warrant) from a federal judge. So long as they do not murder, torture or "violate the sexual integrity" of an individual, or "wilfully... obstruct, pervert or defeat the course of justice," CSIS disruption measures would appear to be open-ended.

Why should snatching persons off the street and detaining them in secret under conditions controlled entirely by CSIS not fit under its authorized "measures?" After all, every Canadian citizen's rights under the Charter of Rights, sections 9 and 10 (the right not be arbitrarily detained, and if detained to be represented by counsel and to be protected by habeas corpus) can be overridden by CSIS -- assuming of course that CSIS can persuade a judge to warrant its actions in advance. Since warrants applications are heard and executed in secret, no third parties need ever be the wiser.

Outsource intelligence gathering

This is within Canada. Outside Canada, CSIS has an even freer hand. Under Bill C-51's companion Bill C-44 (The Protection of Canada from Terrorists Act), CSIS is explicitly authorized to investigate threats to the security of Canada "without regard to any other law, including that of a foreign state." No warrant would be required from a Canadian judge authorizing CSIS measures breaking the laws of a foreign country. The extraterritorial application of Charter rights to Canadians outside Canada is a muddy, confusing area of jurisprudence. This opens the door to an alarming possibility.

Here's one scenario: Let's say we have a Canadian believed by CSIS to have been recruited by ISIS. Travelling to or from Syria or Iraq, this person is intercepted and detained by CSIS agents in a third country. CSIS believes this person has valuable intelligence on ISIS, but they are resistant to questions. Restricted by the prohibition against inflicting bodily harm, CSIS decides to "render" this individual to another state, one whose interrogation techniques are not limited by concerns about human rights. Bill C-44 effectively allows CSIS to outsource its intelligence collection to foreign states, so CSIS could be free to use any intelligence extracted by the host country's "enhanced interrogation" techniques.

In other words, it's the Maher Arar scenario, except that in this case it is Canada alone that is responsible for detention and rendition.

To be fair, there is no evidence that CSIS has any specific intention to secretly detain persons inside or outside Canada, nor to render anyone to a human rights abusive state. One would certainly hope they do not have such intentions.

But that is not the point. The point is that Bill C-51 makes such scenarios possible, which is scary. The government's strange amendment about CSIS not having arrest powers can be interpreted as a deliberate diversion to evade a closer look at CSIS's possible detention powers. And that is even scarier. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: