Sometimes the fall of a political leader can tell you as much about the political geography of a place as it does about the character of the politician.

One, after all, creates the other. And the demise of Alison Redford, a millionaire lawyer, is a case in point.

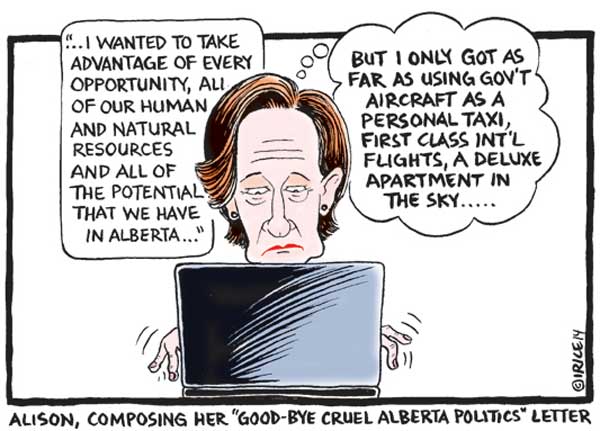

Her misuse of public funds and departure from politics not only mirrors the state of the Progressive Conservative party (it has ruled for 43 years), but reflects something fundamentally wrong with Alberta's democracy.

It's an uncomfortable point. Every petrostate, including Texas and Russia, suffers from an exclusive form of narcissism: oil exporters think they are better than everyone else because they are sitting on piles of the world's most lucrative commodity. In turn, that feeds an arrogant culture of entitlement.

The auditor general's report on Redford's unique approach to travel expenses should also be read as a rebuke of the province's political culture. It is worth citing in full.

"Premier Redford and her office used public resources inappropriately. They consistently failed to demonstrate in the documents we examined that their travel expenses were necessary and a reasonable and appropriate use of public resources -- in other words economical and in support of a government business objective. Premier Redford used public assets (aircraft) for personal and partisan purposes. And Premier Redford was involved in a plan to convert public space in a public building into personal living space."

How then did things get so bad?

"The answer is the aura of power around Premier Redford and her office and the perception that the influence of the office should not be questioned. We observed a tendency to work around or ignore rules in order to fulfill requests coming from the premier's office in ways that avoided leaving the premier with personal responsibility for decisions."

And where did that "aura of power" come from?

Entitlement culture

The auditor didn't mention oil, because it's not polite to talk about the corrosive influence of hydrocarbon revenue in a democracy like Alberta. But every Albertan knows that oil and pipelines pay the piper and call the tune.

When 30 per cent of a government's revenue stream comes from the activities of the world's most entitled industry (the salaries for oil and gas workers are the highest in the world), citizens pretty much turn into apathetic recipients of petroleum welfare, because they don't pay much in taxes.

When oil companies pay for 30 per cent of the province's roads and schools, more than 60 per cent of the population ultimately stops voting. When citizens become subjects, they don't worry about representation. But, like Redford, they quickly learn how to spell "entitlement."

Most Albertans would readily agree that Redford did a much better job of representing bitumen miners than she did governing for ordinary working Albertans. Or the poor. Or First Nations. Apparently, petroleum is entitled more than people, water and caribou in Alberta.

The industry's "aura of power" is now so overwhelming that Redford, in between her globetrotting, even appointed a known oil lobbyist to chair the Alberta Energy Regulator. That took some chutzpah. Her government also removed any mention of regulating in the "public interest" with a new Responsible Development Energy Development Act. How's that for entitlement?

Under Redford, the government also signalled that it no longer wanted to hear from the critics of rapid development at public hearings. Tellingly, the former premier said it was her "prerogative" to determine whom the Queen would listen to, even after a 2013 court ruling described such entitled behaviour as a breach of "the rules of fundamental justice."

No matter. Since the ruling, Redford's ill-fated government denied environmental groups and First Nations access to public hearings another nine times.

Buying political consensus

Alberta's elites and media, a petroleum culture not prone to introspection, haven't read Stanford political scientist Terry Lynn Karl, because they haven't reached the bottom yet.

But no one understands petrostates better than Karl. For 30 years, she has documented how petroleum revenues poison democracies (Alberta), strengthen autocracies (Russia), and spread the contamination of entitlement in public life.

"Oil states can buy political consensus," wrote Karl in a 2007 essay, because petroleum revenue "facilitates the co-optation of potential opponents or dissident voices."

But that's not all. "With basic needs met by an often generous welfare state, with the absence of taxation, and with little more than demands for quiescence and loyalty in return, populations tend to be politically inactive, relatively obedient and loyal and levels of protest remain low -- at least as long as the oil state can deliver."

And then for long periods of time, 43 years in Alberta's case, "an unusual combination of dependence, passivity and entitlement marks the political culture of petroleum exporters."

Maybe Alberta's auditor general could tackle that "aura of power" next. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: