The B.C. Federation of Labour has just proposed to increase the minimum wage in British Columbia to $13 per hour. In short, it's about time. With this proposal, B.C. joins the minimum wage debate that has erupted across North America. The debate is much needed: poverty wages have no place in today's economy.

In the United States, the lowest-paid, most precarious workers stood up and demanded a higher minimum wage at great personal risk, and politicians have slowly started to heed their call. President Obama recently agreed to raise the minimum wage for federal contractors from $7.25 to $10.10, a 39 per cent increase -- notably larger than the 27 per cent increase proposed by the B.C. Federation of Labour.

Seattle and other American cities are seriously considering the $15 minimum wage proposed by striking fast-food workers. Ontario, too, has announced plans to raise its minimum wage to $11 and index it annually to inflation; however, groups there have called for a more substantial increase that brings someone working full time at the minimum wage above the poverty line.

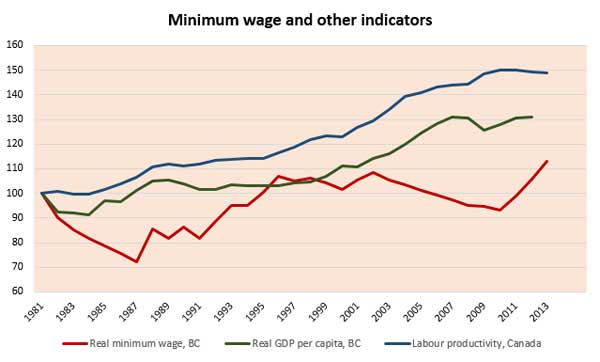

Here in B.C., someone working full-time, year-round on the minimum wage also falls far below the poverty line, especially in urban areas. A salary based on working 35 hours per week and 50 weeks per year at the minimum wage is almost $18,000, over $5,500 short of the Canada-wide low income cut-off for large cities and still over $2,000 short in medium-sized towns. Add in a dependant and the minimum wage becomes even more of a poverty wage. The comparisons to a living wage are even starker: a living wage is $19.62 in Metro Vancouver and $16.37 in the Fraser Valley. Looking at the data, we see that the real minimum wage in B.C. has stagnated for the past three decades, at the same time as labour productivity and GDP per capita have been steadily rising.

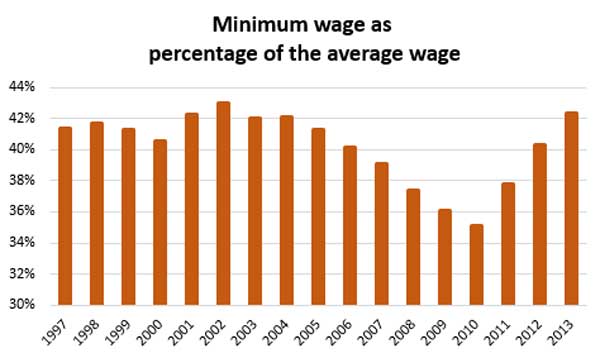

Another useful measure is the proportion of the minimum wage to the average wage. A recent report from the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives recommended a minimum wage at 60 per cent of the average wage as a good target, citing the experiences and policy goals of other developed countries. For comparison, the proposed $13 minimum wage is less than 53 per cent of the current average wage, while the current minimum wage has just recently clawed its way back above 40 per cent of the average from lows around 35 per cent.

Despite the increasingly universal and continent-wide calls for increasing the minimum wage and a demonstrated need for a raise in our local context, raising the minimum wage remains a controversial issue. Over the coming days and weeks, we'll hear many of the same tired arguments. For each one of these arguments there is a mounting pile of contrary evidence from across the continent. We should not be so vain as to think that this evidence wouldn't apply to B.C.

1. Raising the minimum wage kills lots of jobs. A wealth of recent studies, primarily from the U.S., has seriously questioned this favoured trope of minimum wage opponents. I analyze these studies in more detail and within the Canadian context here. In short, the issue comes down to the arcane topic of statistical methods. While some older studies, both American and Canadian, found decreased employment alongside minimum wage increases, they used heavy-handed methods. They were unable to isolate the effects of minimum wage increases from the raft of other factors affecting employment at the same time.

Many of the newer studies use much finer-grained methods, for example, looking at thousands of pairs of neighbouring counties on U.S. state boundaries that share many of the same characteristics but are subject to different minimum wage policies. These generally find either no significant effect at all or a relatively negligible negative effect on employment coming from raising the minimum wage (see this powerful graph). Lower turnover, wage compression, efficiency improvements and increased demand are only some among a host of reasons that may contribute to minimum wage increases not having a significant impact on employment. A larger increase in the minimum wage may lead to some small number of jobs, or more likely hours being cut, but it is useful to remember that a 20 per cent wage hike that reduces a minimum wage worker's hours by five per cent still leads to a sizable net benefit for that worker.

2. Raising the minimum wage doesn't help the very working poor it targets. The same methods discussed in the last point were also applied to looking at how raising the minimum wage affects poverty. The results were similarly hopeful. One major, very recent study that looked at mountains of data from across the U.S. and compared results with previous findings concluded that a 10 per cent increase in the minimum wage is associated with a 2.4 to 3.6 per cent decrease in the poverty rate, an estimate roughly shared by other recent studies. Don't be fooled by those who claim that Canadian studies don't show the same results -- methods make a difference!

3. Minimum wage earners are rich teenagers. One of the most comprehensive Canadian studies to look at the demographics of minimum wage earners comes from Ontario. There, the Wellesley Institute calculated that nearly 40 per cent of minimum wage earners are over 25 years old. In addition, a disproportionate number come from demographic groups further marginalized in the labour market: women, recent immigrants and racialized minorities. The Ontario study also looked at those making within $4 per hour of the minimum wage; here, the demographic reality of low-wage work moves even more strongly away from the stereotype of a rich teenager flipping burgers. Over 60 per cent of this broader group of low-wage workers is over 25. While the proportion of the overall workforce working for minimum wage in B.C. is smaller than it is in Ontario, there are few reasons to think that there would be major differences in the demographics of minimum wage earners in this province or that the same trends would not apply.

4. There are better ways to reduce poverty. Perhaps a better way of putting this is that there are numerous ways to reduce poverty, all of which play their part. The minimum wage is only one of many tools in the shop, but it is one we should be using if it is available, especially in light of the arguments above. The minimum wage helps the lowest-paid workers not only achieve gains in income and move closer to escaping from poverty, it gives them more bargaining power in their highly-skewed relationship with employers. A minimum wage hike is best seen as part of a broad poverty-reduction strategy that includes all those other tools we'll be hearing about from right-wing opponents, like tax credits, and some tools they may not mention, like just EI and welfare rates, effective enforcement and strong social programs.

5. Economists are united in their opposition to minimum wage increases. If all the studies cited in the arguments above weren't enough evidence for the fact that the economics profession holds no monolithic position in the minimum wage debate, consider a public letter circulated in the U.S. Signed by over 600 economists, including seven past Nobel Prize winners, it argues that "increases in the minimum wage have had little or no negative effect on the employment of minimum-wage workers, even during times of weakness in the labour market... [and] could have a small stimulative effect on the economy as low-wage workers spend their additional earnings, raising demand and job growth." The debate is not a false one between hard-nosed economics and feel-good politics. There are many good reasons to raise the minimum wage and economic reasons are clearly among them.

Raising the minimum wage will not solve all the problems of the working poor. Some individuals may be negatively affected, but the net benefit not just to society as a whole but to the lowest-paid, and often hardest-working, individuals as a group is clear. Let's not allow the proposal to raise B.C.'s minimum wage to $13 become a be-all-end-all controversy that pits a false economics against the real needs of British Columbians. Let's hope instead that this proposal is just the start of a province-wide conversation about justice and fairness for workers. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Labour + Industry

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: