Last June, I wrote about the outbreaks of H7N9 avian flu and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome, and what they told us about the politics of healthcare in China and the Gulf states -- especially Saudi Arabia. China, having lost face by suppressing news of the SARS outbreak in 2003-04, was now being much more open; Saudi Arabia, by contrast, was revealing as little as possible.

Since then, H7N9 cases dropped off sharply over the summer and rose again in the fall. Meanwhile, MERS cases have continued, most of them in Saudi Arabia but with a few in the United Arab Emirates and Qatar.

According to the Reporters Without Borders press freedom report for 2013, China ranks 173rd in the world, just below Vietnam and only five ranks above North Korea. Saudi Arabia ranks 163rd in the world in press freedom in 2013 (down 5 ranks from 2012). Nevertheless, China has dutifully reported its H7N9 cases in some detail, while the Saudis and their Gulf neighbours say almost nothing.

You might argue that it doesn't matter. Since MERS was first identified in Saudi Arabia in September 2012, about 170 people have caught it, and around 75 of them have died of it.

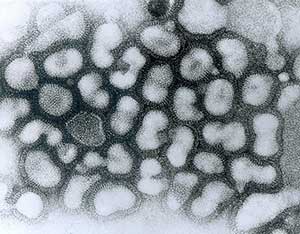

Meanwhile, between the first announcement on H7N9 on March 31 and December 20, the European Centre for Disease Control reports 147 confirmed cases and 47 deaths.

Those are negligible numbers. You are more likely to win the lottery than to contract either disease. But health workers worry about them, partly because they both kill a high proportion of those infected: roughly 44 per cent with MERS and 32 per cent with H7N9.

Those are not negligible numbers, and if either virus figures out how to jump effectively from human to human, it could become the next Spanish flu. The new diseases are therefore useful as tests of the global health system, which of course is far larger and stronger than it was when Spanish flu killed some 50 million people between 1918-19 -- about five per cent of those it infected.

Report at once

Both China and Saudi Arabia are signatories to the International Health Regulations, which stipulate that four diseases must be reported "immediately" to WHO: "A single case of smallpox, poliomyelitis due to wild type poliovirus, human influenza caused by a new subtype and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) ... irrespective of the context in which it occurs."

A flood of H7N9 information

The Chinese have reported every case of H7N9 since last spring, including a recent seasonal surge of cases that even turned up in Hong Kong. They have also flooded research journals with hundreds of scientific papers on the virus, and even published a risk analysis in one Chinese journal saying H7N9 could trigger a new pandemic. Regional papers often provide details on local cases that don't get covered in national news reports.

Thanks to this openness, the world scientific community has learned a lot about H7N9, including the frustrating fact that it hardly bothers poultry at all. With H5N1, mass chicken die-offs signal the presence of the disease. With H7N9, you know it's around when humans get sick. Even then, it's very rare. (A brand-new avian virus, H10N9, was announced in China in mid-December.)

Yet despite the handful of cases, China has shaken up the food supply for a billion people, shutting down "wet markets" (where live poultry are slaughtered in front of the customer) and demanding frequent sterilization of all markets where poultry are sold.

A drought of MERS information

Meanwhile, the Saudis have been telling the world as little as possible though MERS has even worse potential. Their ministry of health set up an English-language "corona" page, but it remains often days or weeks behind its Arabic equivalent, which Google Translate can make partially understandable.

The Saudis will tell the world the patient's age and any underlying conditions, and sometimes the gender. If the case is a Saudi citizen or just imported hired help ("resident"), we'll know that too -- a lot of cases are healthcare workers from other countries. We will get pious hopes for divine mercy, or at least that the fatalities rest in peace.

But that's about it, and the Saudi media add little to the official statements. The Saudis occasionally publish a scientific article on MERS, usually with the deputy minister of health Dr. Ziad Al-Memish as lead author.

But almost two years after the first MERS cases, we still have no idea how people contract this disease. We know that camels and other livestock carry antibodies to it, and it seems to be originally a bat virus, but just how humans contract MERS (except from one another) remains a mystery.

In September, frustrated, I posted a memo to the Saudi minister of health, asking for more details about MERS cases. Three weeks later I got a very polite brushoff. The Saudis are clearly content with their communications strategy.

But they are ignoring a worldwide online network of medical experts who are following MERS and H7N9 through blogs and hashtags. Some of them, like Dr. Vincent Racaniello of Columbia and Dr. Ian MacKay of Brisbane, Australia, can interpret the Saudi data as far as it goes -- which isn't very far.

Others, like WHO and the European Centre for Disease Control, seem to be getting a bit more information but evidently can't publish any more than the Saudis will permit. Otherwise the Saudis might shut up completely, the way the Indonesians did over H5N1 cases back in 2008.

The Saudis aren't the world's only public-health hazard. Cuban doctors, returning from Haiti, evidently brought cholera home with them a couple of years ago. The government has barely admitted its existence, even though it's common knowledge among health agencies. The same strain has now shown up in Mexico, with sporadic cases exported to Venezuela, Chile and other Latin American countries.

For that matter, the UN itself continues to deny its responsibility for bringing cholera to Haiti in the bowels of Nepali peacekeepers in 2010. Since then almost 700,000 Haitians have been sickened with it, and over 8,500 have died.

Governments and international health agencies may fear epidemics and pandemics, but what they really dread is political embarrassment. To avoid that awful outcome, they will shrug off any number of deaths. As German physician and politician Rudolf Virchow observed long ago, "Medicine is a social science, and politics is nothing else but medicine on a large scale."

Sometimes it is medical malpractice on a very, very large scale. ![]()

Read more: Health

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: