The City of Vancouver recently released yet another report that advocates for a 12-kilometre subway to UBC: "The UBC Broadway Corridor: Unlocking the Economic Potential by KPMG LLP." The report is not so much a study as an argument, as it provides no detailed economic modeling to support its conclusion: that the building of an expensive underground system to UBC will be cost beneficial. Subways, it should be noted, cost a fortune -- up to 10 times more per km than a modest tram solution, and three times more than the more aggressive and speedier light rail version proposed by TransLink as one of their menu of acceptable options. Have a look here.

While touted in public reports as "the busiest bus corridor in North America,sys" this assertion disguises the fact that the peak hour Broadway transit ridership is, according to informed sources, well under 7,000 per peak hour out to UBC (sadly TransLink does not publish these figures, nor are current bus ridership numbers included in the KPMG report). It is commonly held that the ridership needed to justify a subway is in excess of 20,000 per peak hour. The "Unlocking" report indirectly alludes to this shortfall, responding with a development goal. The report suggests that should the subway be built, it would induce enough development around station areas to house 150,000 new residents -- all this along a corridor that, as defined in the report, includes less than 10 per cent of the city's total land area.

The report illustrates what sort of development might accompany this growth by citing local and distant examples. On the housing/commercial side, the projects at 41st and Cambie (the Oak Ridge Mall site) and the Marine Gateway project at Marine and Cambie are referenced. Both projects are characterized by residential towers above enclosed shopping mall type bases, and are of a density that is tens of times higher than their immediate surrounds.

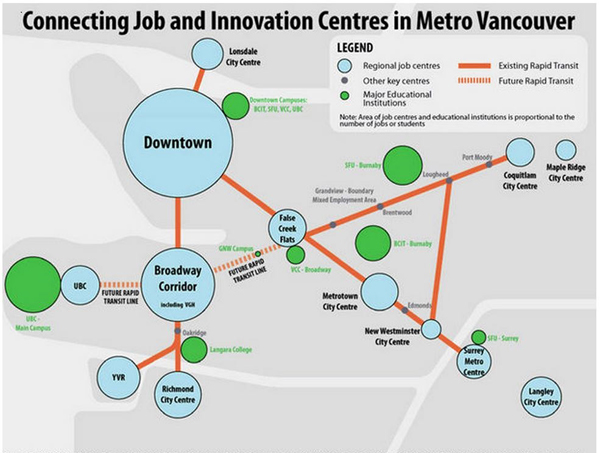

The first illustration one encounters in the report, on page three, is a diagrammatic map of the region at no particular scale. It indicates, as abstracted circles, what it describes as the Vancouver region's significant activity centres, and draws lines to indicate how the Broadway subway would be the missing link between them. There are many aspects of the report worthy of challenge, particularly the lack of detailed computations to support its economic development claims. The report includes some apparent contradictions, such as stating in one section that the corridor is growing faster than expected, and later on stating that growth on the corridor is impeded by inadequate transit. The report also states that TransLink recommended the subway option, which is not the case -- TransLink reviewed a number of options and found more than one acceptable, including more than one variation on the surface light rail strategy.

I will leave those comments for others to make. What is more important to me is how the study reveals what I feel is an oversimplified understanding of how cities operate, and how this oversimplification may have coloured the interpretation of what is, or is not, a reasonable way to spend three billion public dollars. In this case it is fair to say that map making is destiny. The KPMG map depicts the city as a series of significant nodal points -- points they suggest need only to be linked up, across a sort of no man's land of grey, to unlock huge economic development potential. Lost in this conversation is the sense that these grey areas have any significance, or that any other model of how a city functions might more accurately depict it.

Transit design is not my area of special expertise, but the design and function of sustainable cities is. And I know that this way of thinking about cities has produced disappointing results. Cities around the world have been harmed by the very human tendency to oversimplify something that is inherently complex. Regionally we see the results at the Metrotown project in Burnaby, which for all of its success as a transit, office, and commercial hub, does not (yet) succeed as a place, as a downtown, or as a neighbourhood.

There are similar examples elsewhere, in other parts of North America, such as the Empire State Plaza project in Albany, New York. Touted originally in similarly effusive economic development terms as those of the KPGM report, it is now universally viewed as a desolate manifestation of government excess -- abandoned and useless after the white shirted bureaucrats go home. Globally the failure of Brasilia, the planned "all at once" capital of Brazil, is also well known. All of these projects have similar characteristics: they were all imagined as if cities were made up of nodal points of great size and significance, distinguished by function, needing only the slender thread of an expensive transit system to make them hum.

Cities are complex organisms

Oh, if only cities were as simple as machines. The failure of Brasilia stands in marked contrast to the success of Curitiba, also in Brazil, where former mayor Jaime Lerner (an architect as it happens) chose not to think of the city as nodes, but rather as a fabric that could be stitched together along its main threads: he built a hugely successful and inexpensive bus system that served all of its urban corridors and that made him and his city world famous.

The failure of Brasilia also stands in marked contrast to the much more recent success of the Colombian city of Medellin, where relatively cheap transit, in the form of aerial cable cars and outdoor escalators, cured a dysfunctional city. Former Medellin mayor Sergio Fajardo (son of an architect and himself a mathematician) became famous for promoting a truly sustainable urban design strategy, a strategy later called "urban acupuncture." In his view the city was not like a machine, but was much more like a human body.

Fajardo consequently concluded that the ailments of his city could be "cured' through strategic and gentle interventions -- thus, the term urban acupuncture. During his two terms and the decade since much has changed. I provide only one indicator. The rate of death to violence within this once notorious drug capital has fallen by 90 per cent.

Vancouver's future: yours?

So what are the lessons to draw from this, and how might they affect our response to this latest proposal for an expensive piece of infrastructure along Broadway? As a professor at UBC, I have the good fortune to interact each year with many very smart young men and women. In one of our sustainable urban design studios we asked the students: what would the city of Vancouver look like in 2050 if it was sustainable?

Two maps depict the world of the city in very different ways. On the top the KPMG map shows Vancouver and its environs as a collection of bubbles linked by transit. Areas between are grey and suggest insignificance. On the bottom is a map produced in 2010 by UBC Landscape Architecture and Planning students, showing the city as layered systems of green infrastructure, connected centres, green jobs, and continuous habitat.

In our UBC sustainable design studio we imagined a city of 1.2 million, roughly twice what it is now. We asked the participants to also double job sites. We asked them to take lessons from other successful and sustainable cities, and apply them to Vancouver. They discovered that cities can be most accurately described, not as distinctly different nodes connected by transportation links, but as systems, systems that superimpose on each other.

These city systems are, in their most elemental form, jobs, movement, ecology, and community. If maps are destiny then these students illustrated a markedly different future than the one suggested in the KPGM report. When the city is viewed as interactive systems, a very different path toward sustainability is revealed. Rather than connecting more important nodes at the expense of the less important in-between places, everywhere in the body of the city is important and connected. Rather than one or two places for jobs, jobs are everywhere. Rather than ignoring the ecology of the city, ecology is everywhere, and rather than a city that has multiple million plus square-foot shopping/high rise tower megaprojects, strung along one corridor, you have actual neighbourhoods.

This then, it seems to me, is what is at stake at this juncture. Do we want a city of nodes, a proliferation of Metrotown-type shopping centres that simply cannot be healed into the existing fabric of the city? A sort of "podium world" linked via underground subway tubes, ignorant of the city around it? Or do we want something else? Something more like Broadway in Kitsilano as it now exists, only better? Something more like Commercial Drive as it now exists, only better? Something more like Main Street as it now exists, only better? Something more like Hastings Street in Sunrise as it now exists, only better? Something more like Fraser, Dunbar, 41st in Kerrisdale, as they now exist, only better?

What do we want? This is a very big decision. ![]()

Read more: Transportation, Urban Planning + Architecture

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: