An extremely expensive decision for taxpayers looms near, and those making it are working with costs figures for light rail systems that seem inexplicably high, demanding closer scrutiny.

TransLink will soon be releasing its decision on a proposed transit technology for the Broadway Corridor. Two rounds of public consultation were completed for the study -- in the springs of 2010 and 2011. And now both the City of Vancouver and the University of British Columbia are already calling for a bored tunnel to accommodate a SkyTrain-like system along Broadway.

TransLink's discussion has revolved around the choice of system technology, with the options of improved bus service, a SkyTrain extension in a deep bore subway tube, a surface light rail line, as well as different combinations and iterations of each. Hired consultants Anthony Steadman and Associates estimated that the total capital cost of choosing a 12-km light rail system from Commercial-Broadway SkyTrain Station to UBC would be $1.1 billion. This compared to a $3-billion cost for a fully underground "SkyTrain" type system.

While the cost savings for a surface light rail system are clearly substantial, the advantage erodes when the "combination" systems are examined. "Combo 1" would have a subway extend from Commercial Drive station to Arbutus St., there to shift to a light rail system extending to UBC to the west and back via Granville Island and Science World to end downtown. This alternative has received the most formal and informal support in the city. However, at a cost of $2.4 billion, many logically question why you would want to have two different technologies on the same line when for a "mere" half billion more you could zip all the way to UBC underground and in less time.

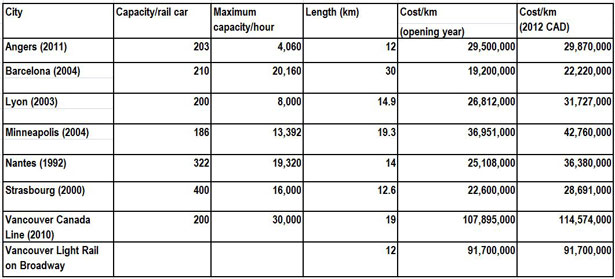

Lost so far in this conversation is an oddity. It appears that the assumed price for the light rail option is roughly three times higher than the actual costs incurred to construct similar systems in Europe and the U.S.

The cost per kilometre for the surface rail option also approaches the cost per kilometre for the recently completed Canada Line, a largely underground system. For a surface system to cost as much per kilometre as an underground system seems hard to fathom. Such a high cost for surface light rail seems even more inexplicable given the fact that the European systems navigate urban infrastructure which is much more complex to adjust for new light rail infrastructure -- all at a fraction of the cost per kilometre.

Absent a detailed explanation for this huge disparity, it would seem that a correspondingly low price tag should be realistic for the construction of a surface light rail system in Vancouver. Using figures from European examples allows us to speculate that a light rail system (exactly as pictured in consultation documents emanating from TransLink), could be built between the Commercial Drive station and UBC in the range of $360 million -- $740 million less than TransLink's estimate.

Curious about this discrepancy we investigated, as best as we could, using publicly available documents. In the interest of enhancing the conversation before this important decision is made, we share our results in this article.

How we got our figures

To make this comparison as fair and complete as possible, we provide cost and capacity comparisons between the current TransLink estimates and the actual construction costs for similar systems worldwide. We have also adjusted these figures to 2012 dollars. Finally we have ascertained the hourly capacity of these systems. This last point is important, as many knowledgeable voices have argued that only a SkyTrain type subway has the capacity to serve the Broadway corridor. This argument has convinced many that SkyTrain is the only reasonable option. However, many of the systems in our comparison exceed the capacity requirements for the corridor. In some cases they exceed capacity requirements quite substantially. In others they could easily exceed the capacity requirements for the Broadway corridor if more and longer cars were added and/or electrical systems were upgraded for more trains.

This question has a regional significance. Should a lower price tag be achieved, the savings could presumably be passed on to transit projects elsewhere in Vancouver and the Lower Mainland, improving access to zero greenhouse gas transit, helping our region meet its 2020 and 2050 GHG reduction targets (Greenhouse Gas Reduction Targets Act of 2007). The research conducted here is preliminary, seeking principally to provide a frame of reference for Vancouverites (and those elsewhere in the region and province) who take a keen interest in the future of public transit, and the long term sustainability of our region.

What do we mean by light rail?

The variety of terminologies used for light rail transportation projects can be confounding. Here, we are concerned specifically with transportation systems that are nearly identical to the light rail technology assumed by TransLink for its alternatives study. These run at-grade, on the street, in lanes that are separate from car traffic, and at a speed that is high enough for the express service. All of the systems we compare are double-track (two trains, running in opposite directions, operating simultaneously), and none run on former railroad lines. As there are plans to plant grass along segments of the tracks, we give some special consideration to similar applications elsewhere.

Why does the cost of Vancouver's system stand alone as the most expensive of the lot, in one case by a factor of four? The comparison systems do not sacrifice speed or capacity. They carry more than 20,000 passengers per hour on average, and could carry many more if frequency or car length was increased. They each use vehicles with level boarding, meaning passengers can disembark at a curbside stop, rather than at a raised platform. The stations are simple, like our existing bus stops. With the exception of Minneapolis, the systems have at least partial grass tracking.

A note on the Minneapolis system. The higher price for the Minneapolis LR system in comparison to the European examples is attributable to a 3-km tunnel bored through the ground under the airport. That infrastructure is not needed on Broadway; and still, the line was completed at less than half the cost per kilometre of assumed for a similar Vancouver system.

SkyTrain vs. light rail: How much is one minute worth

A favoured point of opposition to light rail is its lower speed when compared to a SkyTrain system. Here, we look to details of the UBC Line Study for answers. TransLink estimates that a trip by LRT from Commercial-Broadway Station to UBC would take 26 minutes, while a SkyTrain subway transit ride would take 20 minutes. If that is the case, what is the price of each minute saved?

With the SkyTrain priced at $3.2 billion, the SkyTrain will cost $25 million a year per minute saved, over an amortization period of 30 years.

That means that, for every one of the 50,005,000 riders expected in a year, taxpayers will pay $3.00 for each trip, or a total of $150 million annually, to save six minutes.

Capacity

A modern street-level tram system has, maybe surprisingly, the same or higher capacity than SkyTrain. By looking at the light rail model that was chosen for the temporary Olympic tram one can see why. These trams can be conjoined to be very long. Thus the only element limiting capacity is the length of blocks along the route. Even Vancouver's shorter blocks are 80 meters long (most on Broadway are twice that). An articulated Flexity tram under that length would provide an hourly capacity of up to 40,000 passengers per hour.

This is higher than the Canada line, the capacity of which is limited by its short stations and consequent two car maximum length per train. (See sidebar to see how we calculated comparable capacity in other cities.)

Why is the estimated cost for Broadway light rail so high?

Seeing projects that are even less expensive than those in our comparison, such as the recent light rail extension in Helsinki, emphasizes the need to ask questions about over-design and efficiency when we make choices to implement new transportation systems. If the high cost of this estimate derives from gold-plated requirements for completely rebuilding streets traversed, is this really required?

Portland recently added rail transit downtown with a bare minimum of street disruption. No major intersection reconstruction. No major utility changes. Bare bones platforms. Current cost estimates provide little in the way of detail to assess the portion of the budget attributable to rebuilding intersections, locating platforms, accommodation for ticket vending and platforms, etc.

But there's no time like the present to push for the better use of transit dollars, to the benefit of taxpayer wallets, commuters, and residents across the region. Our region has come to the verge of committing to surface rail too many times to be derailed yet again by unrealistic and potentially unfair cost and function comparisons with SkyTrain.

Here then is our request to TransLink, Vancouver City Hall, and other public transportation researchers in the Lower Mainland: Why is the estimated cost for Broadway light rail so high? Let's find out. The answer could be worth billions.

Read more: Transportation, Urban Planning + Architecture

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: