Trans Mountain says it is in the process of wrapping up work to install its pipeline through a sacred Secwépemc site, bringing its expansion project one step closer to completion.

The pipe installation, which involved digging a 1.3-kilometre trench through an area with a known burial site, was allowed to proceed after years of back and forth between the company, the Stk’emlúpsemc te Secwépemc Nation and federal regulators.

The Canadian government bought the pipeline nearly six years ago and vowed to move ahead with its expansion, saying it was in the public interest. It is managed through a Crown corporation.

“It’s devastating to many people that this happened,” said Mike McKenzie, a Secwépemc knowledge keeper. “Canada had a serious obligation to the Stk’emlúpsemc te Secwépemc and all Canadians to uphold Secwépemc law in a good way, to embody reconciliation in their work.”

The pipeline expansion project, which is years behind schedule and nearly $30 billion over budget, was to be delivering heavy oil to the coast by the end of March. That’s now unlikely — and the delays are costing Canadians about $200 million a month in lost revenue, the Crown corporation says.

Pressure to complete the project has resulted in recent regulatory flip-flops, including a deviation allowing Trans Mountain to trench through Pípsell rather than drill beneath it, in part because of time constraints.

The Stk’emlúpsemc te Secwépemc Nation, which includes the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc and the Skeetchestn Indian Band, has opposed pipeline construction through Pípsell on several occasions, but consented to drilling under the site in order to minimize disturbances to the ground. The nation didn’t respond to The Tyee’s interview requests.

The Tyee also requested an interview with Trans Mountain, but the company declined. It has publicly stated that it will not provide media interviews as it is “fully focused on the completion of the pipeline.”

Instead, it responded to many of The Tyee’s questions with links to its website and that of the Canada Energy Regulator. It said that trenching through Pípsell is complete and work to backfill bore shafts used for drilling was expected to wrap up in late February.

Why is Pípsell significant to the Stk’emlúpsemc te Secwépemc?

For at least 10,000 years, Secwépemc people have moved about the region that is currently known as south-central B.C., travelling with the seasons to areas used for various cultural activities.

Among the sites used by the nation for millennia is Pípsell. Located at Jacko Lake, about 10 kilometres southwest of Kamloops, Pípsell is a refuge for deer, moose and a variety of other animals with cultural and spiritual significance, the Stk’emlúpsemc te Secwépemc Nation said in documents filed with the Canada Energy Regulator. Today, nation members continue to use the area for hunting, fishing and plant harvesting.

It is also a place of profound spiritual significance.

“The entire Pípsell area is a sacred site,” the regulator wrote, summarizing the nation’s position. It is a “cultural keystone place” critical to community identity and well-being, and protecting it is the nation’s legal and spiritual obligation.

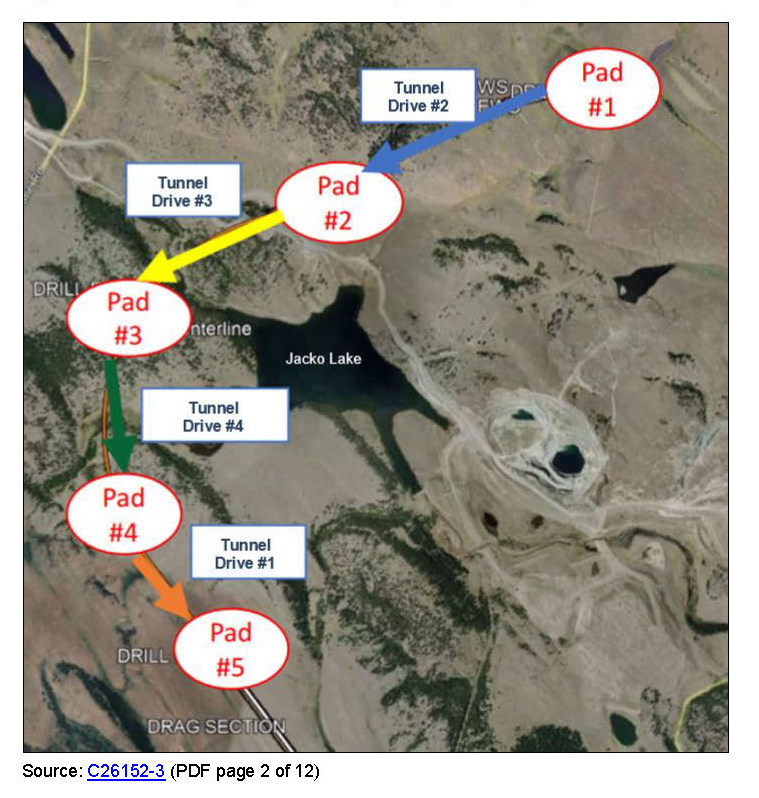

Among Pípsell’s most significant cultural features is a burial mound, believed to contain the remains of a Secwépemc ancestor. This mound is located within 10 metres of a pipeline drilling work site.

Given the area’s significance, Elders have been clear that Pípsell should not be touched, McKenzie said.

“There are burials all through there. My grandmother said that we have no way of knowing exactly where all of them are,” McKenzie said.

“She was talking about the whole place being a burial and prayer grounds,” he added.

It’s not the first time the Secwépemc have stood up to industrial development planned for Pípsell. Within the past decade, the nation successfully fought plans for an open-pit gold and copper mine in the area.

In a March 2017 decision submitted to B.C.’s Environmental Assessment Office, the Stk’emlúpsemc te Secwépemc Nation declined to give its consent for the Ajax mine, saying its proposed location at Pípsell “is in opposition to the SSN land use objective for this profoundly sacred, culturally important, and historically significant keystone site.”

“Our spiritual and religious connection to Pípsell, a sacred place, is irreplaceable,” the nation wrote. “We cannot transport our connection to Pípsell to another site. Pípsell is marked by our people, one of our central stseptekwll [oral histories] originates in the place itself, which makes this a sacred site for our people.”

That June, the nation designated the area a Secwépemc Nation Cultural Heritage Site.

In the end, the Ajax mine was not approved. In December 2017, the B.C. Environmental Assessment Office recommended against the project, in part due to impacts to Secwépemc cultural heritage. The EAO determined there were “serious impacts to rights related to the practice of cultural and spiritual customs, ceremonies and traditions” at Pípsell.

“We acknowledge the importance of the area to the culture of SSN and find, in these circumstances, these impacts unacceptable,” the province wrote in its decision.

The decision led the Elders to believe the site would be permanently protected, McKenzie said.

What is the Trans Mountain expansion project?

Under its previous owner, Texas-based Kinder Morgan, the Trans Mountain pipeline had been in operation since the 1950s, delivering both refined petroleum and crude oil from the Alberta oilsands to a terminal in Burnaby.

In 2013, the company applied to twin the pipeline. The second pipeline would carry “heavier oils,” it said, such as bitumen, and nearly triple the project’s capacity to 890,000 from 300,000 barrels a day.

While the expansion project was approved by the federal government in 2016, the decision was overturned in August 2018 by a Federal Court of Appeal, in part due to inadequate consultation with First Nations.

Just months later, Canada bought the pipeline for $4.5 billion and began moving ahead with its expansion despite B.C.’s opposition. At the time, the expansion was estimated to cost $5.4 billion.

In June 2019, the project was again approved, this time subject to 156 conditions. Since then, its costs have ballooned. It is now expected to cost about $34 billion to complete.

With the project now well over budget and behind schedule, the company has begun to cut corners. In a 2.3-kilometre stretch along the Fraser River between Hope and Chilliwack, it recently received approval to swap out planned pipe for pipe with a narrower width, citing “some of the most challenging terrain in North America for pipelines.”

The change required the company to use a supplier external to its approved list, which went against the company’s quality management plan and the conditions of its federal approval.

While the Canada Energy Regulator initially rejected Trans Mountain’s application for the revised plan, it changed course a month later in response to a followup request, The Tyee recently reported.

Why the change of plans at Pípsell?

Harder-than-expected geology, cost overruns and a time crunch have also been blamed for changes to pipeline construction through Secwépemc territory.

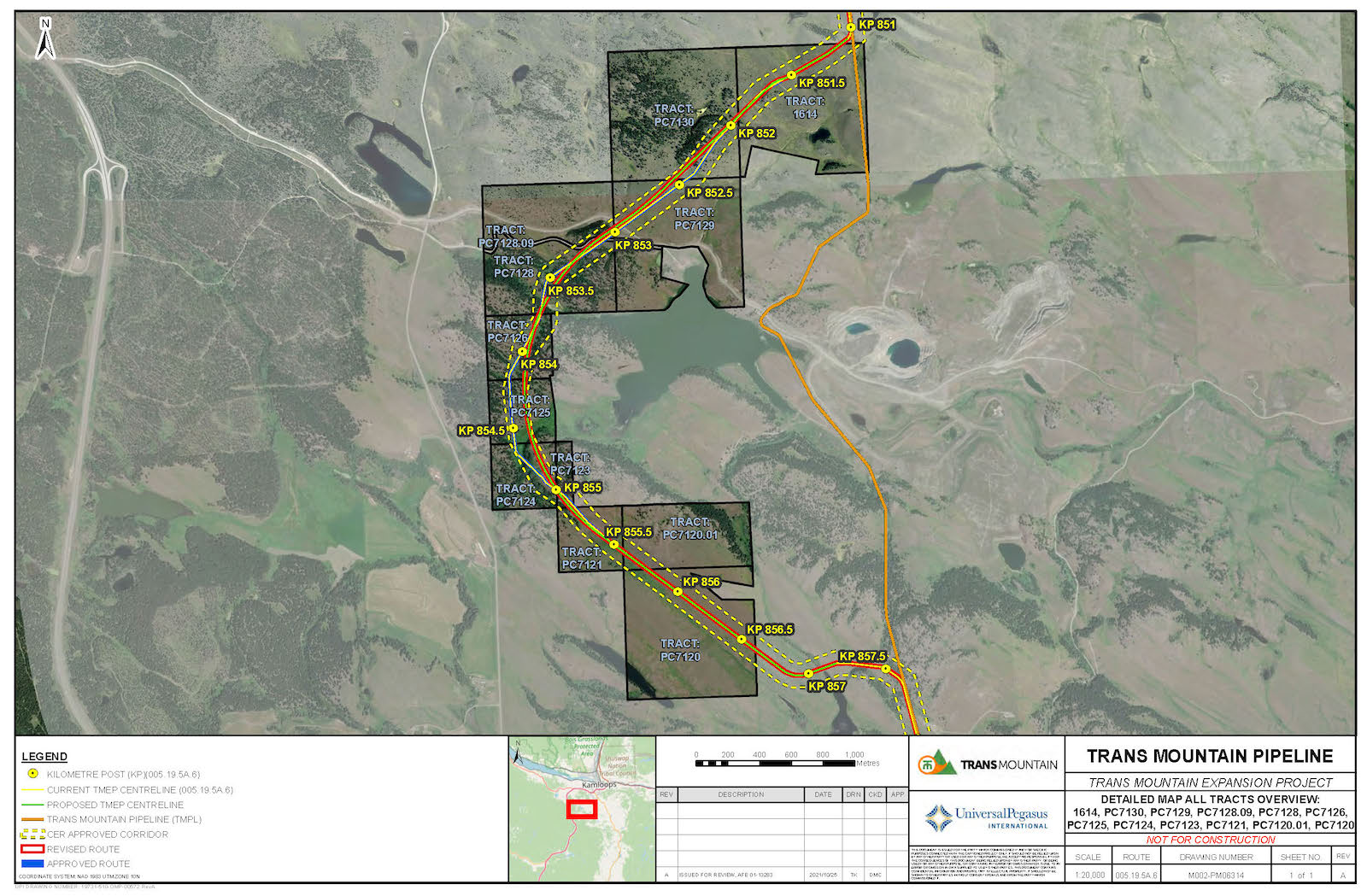

The section that passes through Pípsell is one of the few areas along the pipeline route where the expansion project diverges from the original pipeline route, arcing west around Jacko Lake rather than following the original pipe, which passed under an arm of the lake to the east. The company said the new route was meant to reduce environmental impacts.

On Sept. 5, 2019, after Trans Mountain submitted plans for the section of the pipeline route that would pass through the Pípsell area, Stk’emlúpsemc te Secwépemc submitted a statement opposing the proposed route. The nation suggested two alternative routes that would parallel the Coquihalla Highway.

Two months later, the nation withdrew its opposition, saying the company had addressed its concerns.

In February 2022, Trans Mountain applied for a deviation to its original plan. It said it had co-developed, along with the Stk’emlúpsemc te Secwépemc, plans to micro-tunnel, in a series of four sections, for 4.2 kilometres under the sacred area.

The Canada Energy Regulator approved the request weeks later and work got underway in mid-2022.

So, what’s the problem?

By early 2023, Trans Mountain’s micro-tunnelling was running into trouble.

Geotechnical studies had underestimated the hardness of the rock under Pípsell, slowing progress, the company wrote in an application to change its method. In addition, loose ground above the bedrock was causing “upward migration” of the drilling. The company said it spent an additional $32 million trying to resolve the issues before turning to the federal regulator in August 2023.

It requested permission to trench in one 1.3-kilometre section through Pípsell, saying micro-tunnelling was likely to fail and, even if it did succeed, could take more than 10 months to complete. That could cost more than $2 billion in lost revenue, the company said.

Stk’emlúpsemc te Secwépemc opposed the application, noting Pípsell’s profound spiritual and cultural significance to the nation.

But the Canada Energy Regulator approved the change in September, agreeing that micro-tunnelling could ultimately fail. It noted the company’s “extensive and prolonged efforts” to complete the drilling, and the project’s ever-growing price tag.

The regulator also pointed to a confidential benefits agreement, signed by Trans Mountain and Stk’emlúpsemc te Secwépemc, which acknowledged the possibility that trenchless construction could fail and set out financial compensation for any sections where trenching was necessary.

“Both Trans Mountain and SSN were aware from the outset that micro-tunnelling might prove to be infeasible, in which case other construction methods might be required,” the regulator wrote in approving the deviation.

Isn’t it risky to dig through a known Indigenous burial ground?

Joanne Hammond, an archeologist in the Kamloops area, described plans to trench near a burial mound as “ill advised, to say the least.”

“If you have a whole bunch of visible burial mounds, there’s a really good chance that there are some that are invisible as well,” she said. “I wouldn’t risk putting a pipeline, or putting anything, that close to a burial site.”

Hammond said that an archeological assessment for the Ajax mine had previously identified about 50 new sites in the area around Jacko Lake. Additional assessments leading up to pipeline construction identified even more, she added.

“It’s the kind of landscape where, if you look, you’re going to find it,” she said. “The whole landscape is considered a cultural landscape.”

Given high cultural sensitivity throughout the area, Hammond said, there are likely to be strict rules in place for any archeological discoveries.

In approving Trans Mountain’s request to trench through the area, the Canada Energy Regulator pointed to the company’s “robust” mitigation measures in the case it inadvertently unearthed Indigenous cultural heritage.

“These measures include dedicating the necessary time and resources to working with Indigenous monitors at the construction site, avoiding known cultural features and archeological sites, walking the route with SSN Knowledge Keepers prior to construction and following the robust processes and procedures described by Trans Mountain in the event of a chance find,” it wrote.

Chance-find procedures are contingency plans, established prior to construction, that lay out a process in the case that cultural or archeological heritage is unexpectedly unearthed. Immediate steps include stopping work, protecting the area and engaging with the First Nation to establish mitigation plans.

Trans Mountain did not respond to The Tyee’s questions about its chance-find procedures, mitigation measures or Indigenous cultural monitors, instead providing links to its website. In a 2021 handout, it recognized First Nations’ cultural, spiritual and social connection with the land and said mitigation plans are in place to “reduce potential impacts” to cultural heritage.

But in a September 2023 letter to the Canada Energy Regulator, the Indigenous Advisory and Monitoring Committee — a caucus representing the interests of First Nations along the pipeline route — said it didn’t share Trans Mountain’s confidence about its ability to mitigate damage to cultural sites.

“The potential for disturbance of sites of significance and for chance finds should more trench construction methods be authorized in the Pípsell (Jacko Lake) area is likely greater than is presently understood,” wrote IAMC chair Raymond Cardinal, adding that Trans Mountain had “vastly underestimated” the number of cultural sites along its route.

When cultural sites are discovered, they are most often documented and removed, Hammond said.

“In the case of a pipeline, where it can’t be moved, it almost always means excavating it,” she said. For an archeological discovery, B.C.’s Archeology Branch and the First Nation would be notified and negotiations between the archeologist, the First Nation and the company would commence. In order to remove the site, the company would have to apply for an alteration permit from the province. In the case of human remains, the RCMP and BC Coroners Service would also be notified.

Most likely, what would happen next is “systematic data recovery,” she said. The site would be dismantled in exchange for the archeological knowledge.

In the end, the decision to grant Trans Mountain’s deviation came down to time and money.

The company said flooding, wildfires and the COVID-19 pandemic were factors that delayed the project. It recently pushed its March 31 completion deadline to later this spring.

In its application to the Canada Energy Regulator, the company expressed concern about delaying its in-service date, referencing the monthly $200-million cost in lost revenues. In his response letter, Cardinal said that First Nations shouldn’t have to pay the price.

“Indigenous communities should not bear the consequences of inadequate planning or intervening circumstances,” Cardinal wrote. “These justifications do not account for the irreparable harm to SSN’s spiritual and cultural connections to the Pípsell (Jacko Lake) area.”

The Tyee asked Trans Mountain to respond to the criticism.

“We recognize the Pípsell area is of sacred importance to the Secwépemc People and are committed to remaining respectful of the spiritual and cultural significance of this land,” a spokesperson wrote in response. “We value our partnership with Stk’emlupsemc te Secwepemc Nation.”

The trenching is complete. Now what?

As the work wraps up, the public, and even Stk’emlúpsemc te Secwépemc Nation members, may never know what, if anything, it revealed.

Archeology is a necessarily secretive process. Cultural heritage sites are kept confidential to keep them safe from looting and vandalism. It’s likely that if any significant cultural heritage were discovered, that information would not be made widely available.

“I think the communication between the proponents and the bands is quite plentiful, so the people who are working there would know, but regular citizens wouldn’t have access to that information,” Hammond said.

McKenzie told The Tyee there are “confidential treasures” at Pípsell that the nation wants to keep secret. But as the work wrapped up, he added that he wasn’t aware of any discoveries and the focus now is on finding peace.

“It’s important we spoke up when we did. I did what I could,” he said. “I personally do not think it is fair that, including myself, many of our knowledge keepers and our families have had to navigate the challenges associated with these megaprojects.”

Trans Mountain said the pipeline is now 98 per cent complete. It is hoping to have it operational by the second quarter of this year. ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Energy, Rights + Justice

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: