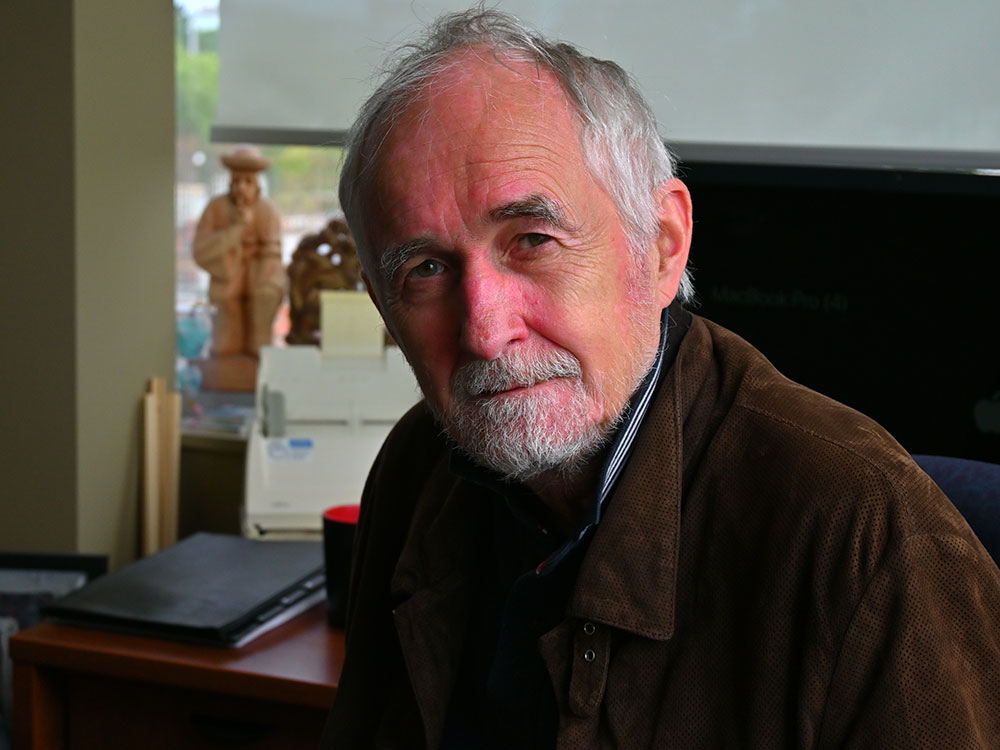

Michael Krausz is a big name in addiction psychiatry. Before settling in Vancouver in 2007 he worked in addiction research in Europe, facilitating addiction-related trials and acting as editor-in-chief for two European scientific journals, European Addiction Research and Suchttherapie.

He’s worked as the medical director of the Burnaby Centre for Mental Health and Addiction with Vancouver Coastal Health and is a member of the scientific advisory board of the Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse and the e-mental health steering committee for the Mental Health Commission of Canada. He teaches psychiatry at the University of British Columbia and is the Providence Health Care leadership chair for addiction research at the university.

Krausz’s work explores how substance use disorders and trauma feed into the toxic drug crisis, which, as of September 2023, has killed 1,629 people in British Columbia this year and 12,929 since a public health emergency was declared in April 2016.

Unregulated drug toxicity is now the leading cause of death in B.C. for people aged 10 to 59, according to the BC Coroners Service.

Krausz is highly critical of the B.C. government’s approach to the overdose crisis, particularly of its strategy to separate psychiatry and treatment, and its unwillingness to set aside political posturing to work together to find a solution.

The Tyee spoke with him to ask how he thinks B.C. could reduce the number of deaths from toxic drugs. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The Tyee: To start, can we get a definition for what substance use disorder is?

Michael Krausz: It’s shifted a lot over the last 30 years. It’s defined as a group of conditions which are based on the use of specialty psychotropic substances and coming with a certain degree of tolerance and dependence.

It comes with a large degree of complex and concurrent mental and physical disorders. That’s the reason I’m sitting here as a psychiatrist, dealing with that population and the treatment of the patient.

This is intentionally oversimplified, but if you had to choose one thing that is driving the number of deaths from toxic drugs right now in B.C., what would it be?

There are two main factors. First, this is a long-term issue that started in about 2014. It has a lot to do with the changing dynamics of drug markets and changing patterns of use. Second, even at the beginning of the crisis we had insufficient treatment systems and systems of response. Now it’s even less sufficient. The challenges are growing and are complex and the country doesn’t have the tools to deal with it or an appropriate response.

For example, opioid agonist therapy [prescribed opioids that prevent withdrawal symptoms and help patients reduce illicit use and improve quality of life] is very narrow and not based on evidence. Treatment options for people with primarily fentanyl use is extremely limited. Psychosocial care is extremely limited and not available for most patients. There is no specialized overdose care for adolescents or young adults or high-needs patients. I think it’s a misery.

What do you mean by “very narrow” in terms of opioid agonist therapies?

Canada has one-third of the treatment options Europe does and there’s limited medications too. And medications that are used very successfully in other countries are not used here. The capacity of specialty clinics is very small, like the Crosstown Clinic here in Vancouver. So patients have extremely limited coverage. How does that help bring down fatality numbers?

There’s a small minority of people who have effective and high standard quality treatment but they’re the most high-risk patients we have in the whole mental health field.

In 2021 the number of overdose fatalities was much higher than COVID-19 fatalities.

All the measures the government and other authorities were developing failed — otherwise the number of fatalities would have gone down. The government talks about toxic drug supply but not about themselves and their role in this mess.

What should government’s role be, then?

Well let’s look at the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. All levels of government acted and invested billions of dollars, not millions, to develop new medications. They developed a clinical research program immediately that was very supported and had academic oversight and high-level monitoring of the whole program. There was this really big effort to understand what was going on.

It can take us months or years to get access to data about overdose deaths.

In B.C. the focus is very much on safe supply and safe injection but not on treatment, psychosocial factors or outcomes. If you’re saying we want to prevent overdose fatalities and the numbers are still high, you have to ask, “What are we doing wrong?” And these numbers are absolutely historic. This is the biggest mortality crisis in the whole area of mental health and substance use.

I recently learned Canada had more overdose fatalities in a year than the whole European Union.

B.C. alone has more overdose deaths than Germany, which has 10 times as many citizens. Seven people are dying every single day — it was six per day last year. We have a catastrophe on hand and there’s no sense of crisis. From my perspective what the government is doing is relatively ineffective, to describe it mildly.

Your work has noted how one in five global deaths is related to substance use and 70 per cent of those are opioid related. Are these numbers because of increasingly potent and unpredictable substances like fentanyl and its analogues?

Drug markets are changing due to the availability, surprise and purity of certain substances and the expectations of drug users.

If you look at B.C. it’s nearly impossible to buy heroin on the street. Fentanyl is cheaper, has a higher level of purity and is produced in B.C. so it’s very available.

It’s been this way since 2019, when you saw the extremely high number of fatalities kick in. Fentanyl creates dependency in four weeks and there’s nothing on offer in terms of good, integrated opioid agonist therapy programs which are taking care of these patients in a pharmacological and psychosocial way and offering social support and helping them stabilize overall.

You know, like all of the good things that are happening for COVID-19 patients where the whole health-care system was reorganized to help them. With overdoses they’re just distributing high-potency psychotropic substances and not much else. For young people there’s nearly nothing in place. These harms are all public, it’s all known. And there’s no response. Ignorant.

I am extremely concerned. I think synergy is possible and helpful in solving some of the problems we have here in B.C. but people are more concerned about their specific power influence. Being right or wrong is much more important than saying “OK, how are we collectively going to bring down the numbers of over 2,000 fatalities per year because these numbers are unheard of?”

One of the biggest populations growing in fatalities is adolescents and young adults. In the U.S. you’re losing hundreds of thousands of lives.

Canada and the U.S. are world-leading. Some countries in the Baltic states in Europe have extremely high numbers of overdose cases but it’s interesting that globally, the majority of countries are still not comparable to us.

Your research notes how these numbers could be about to get a lot worse because of nitazenes, which are synthetic opioids that are more potent than fentanyl. What role are these overly potent substances playing?

Instead of focusing on a specific drug, let’s look at the situation around synthetic drugs, or built high-potency opiates. Heroin is synthetic because it’s not an organic substance — that’s opium.

Fentanyl producers are in regional labs and they’re exploring even higher-potency opiates to bring to the market, like nitazene (which is 25 times more potent than fentanyl), carfentanil (which is 100 times more potent) and other drugs that are extremely more dangerous than fentanyl.

More than five per cent of overdose deaths last year included carfentanil, according to the BC Coroners Service. Producers are mixing different substances, which make it impossible for users to handle and to dose.

Producers can always create new niche markets and target populations. They mix in benzodiazepines and create a mixture which is cheaper to produce.

So you’ve got a product that a user cannot handle safely that is highly potent and dangerous.

At the same time paramedics are having a harder time saving people’s lives because they don’t know what the drugs are. It’s becoming even more dangerous and the response is becoming more hopeless.

If producers are creating a product that is so dangerous, don’t you think they’d be worried they might kill everyone who uses the product?

That’s the reason I’m so concerned about adolescents and young adults — there’s always a population coming in and if it’s cheap, easy to access and you’re hooked in four weeks, then producers have no problem finding new customers.

We just did a study on primary fentanyl users [which is set to be published later this year] and to a large degree they said they would like to stop or reduce their use but they don’t know how. There’s no systems of support in place for that.

As these are high-potency opiates the withdrawal management would need to look quite different too and you have to adapt that. But there’s no support for the development of appropriate interventions. They’re planning detox centres for three, four, five years from now.

Imagine if we were only going to start on COVID-19 vaccinations years from now.

Can we talk about the psychosocial aspects of the overdose crisis? In The Lancet you talk about how there’s very little research done on how economic factors, societal factors and individual factors feed into this crisis. What do we know?

One thing is how two-thirds of intravenous drug users, regardless of the substance they are using, report early trauma like losing a parent, significant other, having serious physical or mental health conditions or having suicidal thoughts. Drug users are three times more likely to have trauma compared to the average population.

A really significant reason for starting substance use, especially high-risk substance use like injection or opioids, is related to the attempt to self-medicate.

Opiates are a very powerful antidepressant. For hundreds of years it was the only antidepressant and was regulated in Canada until the 1960s or ’70s.

Looking at our recent study on fentanyl users, the majority are living in unstable housing, living more or less in poverty, are marginalized and have no job. It’s a vicious cycle of poverty, homelessness, high-risk substance use and death.

There’s also a subgroup of users who are suicidal. Analysis of U.S. deaths show about 15 per cent of overdose cases were suicide or the user had suicidal ideations. Another study I did in Germany found 23 per cent of drug users in treatment had attempted suicide. That study just captured a single snapshot of people’s lives; the number of suicide attempts is going to be much higher across their entire lifetime.

Here in B.C. addiction psychiatry has become very marginalized because the government wants to move in a different direction. They don’t think mental health has anything to do with substance use disorder. I think that’s naive.

In most other countries the response and the treatment is always overseen and developed by a specialized psychiatrist.

How do specialized psychiatrists help people to navigate poverty, homelessness, trauma and serious mental and physical health conditions? What could a successful program look like?

This is a very complicated and complex question where I can only share a few summary ideas. Treatment programs for problems with this level of acuity, complexity and mortality need to be extremely accessible. Especially in the beginning of these developments, there is a real opportunity to turn things around. Systematic approach to prevention would be one important step to help youth to understand risk and find alternatives to respond to challenges.

To intervene as quick as possible, what we call early intervention, is something critical. A real scandal is how overdose survivors are treated, or more or less ignored in the U.S. as well as in Canada, as if society is ignoring that. In the U.S. less than 10 per cent of them had access to meaningful care.

High-risk substance use with an increased risk of overdose is a long-term condition, so you need a long-term treatment trajectory integrating all different approaches from rehabilitation to counselling. We need to use all measures to increase the chance of surviving, from psychosocial approaches to sophisticated pharmacotherapies, from outpatient settings to virtual care, and acute care solutions and supported housing.

So where do we go from here?

It’s a political responsibility. Let’s compare to COVID-19. Creating a vaccine, choosing a vaccine based on academic and scientific advice, implementing public health restrictions and choosing the most appropriate, best-trained and informed people to do it are all political decisions.

Saying the overdose crisis has nothing to do with psychiatry, that we need to distribute medication instead of developing comprehensive treatment programs and improving access and quality of care are also political decisions.

That’s a government response and you can measure it against its success and outcomes and correct or ignore it. That’s what’s happening right now. The government is ignoring it with almost no consequences.

We need programs of preventative education but it only works if we have programs in place. Then you can go to schools and say, “OK, if you’re hooked on this here’s where you can go, here’s how you can avoid risk. Here’s how you can manage your risk and here’s where you can go if you want treatment.”

We need programs that are engaging and helpful because retention rates in treatment programs in Canada are very low. People leave quickly because they’re not happy with what they get. ![]()

Read more: Health, Rights + Justice

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: