On a hot morning in the dog days of summer, Nav Kaushal is dancing on the picket line.

A portable speaker blasts bhangra — upbeat Punjabi tunes — mixed with the instrumental from Usher’s “Yeah!” Two security guards from a nearby hotel approach. One takes out an iPhone, squinting as an app measures just how loud the music is.

“Do you need us to turn it down?” Kaushal asks with a smile. “Are you going to get us in trouble?”

The security guard looks up. “You can actually turn it up a bit, if you want,” he responds.

This is day 51 of Unite Here Local 40’s strike against the Sheraton’s Airport Hotel in Richmond. And day one of new noise restrictions on the picket line.

Workers were so loud on earlier days the employer sought a court injunction to stop them.

It is the third time such an injunction has been filed against Unite Here Local 40, a union making noise in more ways than one.

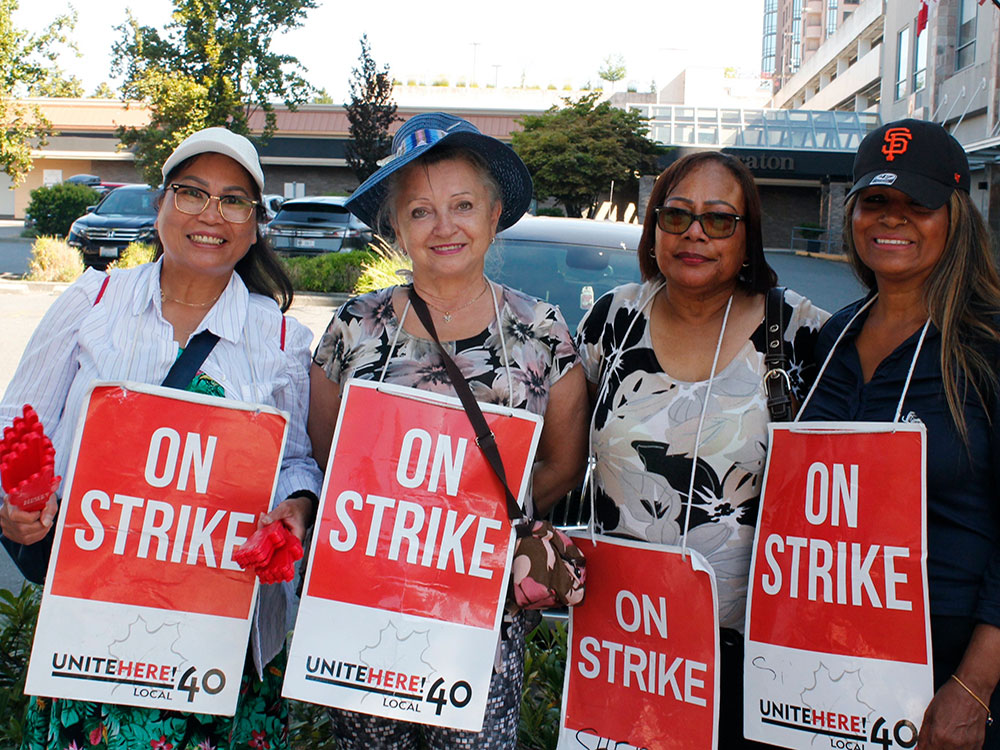

Local 40 represents roughly 5,500 workers across the province, most of them working in hospitality, food services and in airports. The vast majority are women, and many are people of colour.

Right now, many are also on strike. The union is representing striking staff at the Sheraton in Richmond. Another strike at the Radisson Blu hotel in Richmond has gone on for more than two years. The union represents workers at three downtown Vancouver hotels — the Hyatt Regency, Westin Bayshore and Pinnacle Harbourfront — who have also voted in favour of strike action last month. And in northern British Columbia, it has won historic wage increases for food service and housekeeping staff at work camps.

The union also made enemies. Employers have accused the union of twisting the truth about negotiations. One is even suing them for defamation, an allegation that hasn’t been tested in court.

In separate court filings, people who live near the Sheraton in Richmond say the union made so much noise it became intolerable.

The union’s members and supporters say its scrappy approach is part of a strategy to win better wages for workers in the hospitality industry, where some employers have moved to cut wages and benefits in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We have to reckon with this new moment where workers feel squeezed wherever they are, and they see their employers doing well,” said Michelle Travis, the union’s spokesperson. “Out of necessity, we have to seize that moment.”

Showdown at the Sheraton

The ruckus started around 7 a.m.

Every day, union members gathered on the south side of the Vancouver Airport Sheraton to start the day’s picket with a bang.

“You could feel the energy of frustrated workers,” said Felisha Perry, a striking banquet server at the hotel. “There were speakers. There were megaphones. There were drums. There were whistles. Anything loud, you name it, we probably had it on that picket line.”

About 200 workers at the hotel have been on strike since mid-June.

Shaelyn Arnould, a striking barista who sits on the union’s bargaining committee, says it comes down to wages. Workers haven’t seen a raise since 2020, when their last collective agreement expired. Bargaining was put off after the COVID-19 pandemic arrived.

Perry says the company’s last offer included no salary increases for the first three years of the contract, and then 12 per cent over the second three years.

But the union wants the hotel to commit to paying at least a living wage, which the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives calculated as being $24.08 an hour in Metro Vancouver in 2022. That wage is based on what it would take to support a household of four with two breadwinners and two children.

Right now, Perry says some of her colleagues make as little as $16.95 — 20 cents above the minimum wage. Their wages would need to increase almost 50 per cent to achieve the union goal.

“People my age, they want to get married, have a family, settle down, move out, get their own place,” said Perry, who is 26. “But it’s pretty much impossible.”

The ruckus on the picket lines is partially an expression of frustration — a song of anger.

But for some neighbours, it’s been a symphony from hell.

Last month, the company that owns the Sheraton went to court seeking an injunction against Unite Here Local 40 to stop the noise. The main complaints were not brought by the hotel itself but by a small number of residents, who said the din was intolerable.

One long-term resident of the Sheraton who uses a wheelchair said the noise had affected their ability to sleep. A couple with an autistic son said the noise had left their family “stressed, anxious, nervous and on-edge due the relentless loud noises created by the picketers.” The hotel hired security guards who used phone applications to take noise readings on the picket line, and found it was well above the municipal limit of 65 decibels.

Andrea Zwack, the lawyer representing the hotel’s owners, described the noise as “unbearable.” She noted in court there were only two other recent instances where an employer had asked for such an injunction during a strike. They each involved Unite Here Local 40, during separate hotel strikes during the pandemic. In both cases, the injunction was granted.

Zwack said she believed the union knew the noise was a nuisance.

“They tend to represent hotel workers, and this is what they do when they go on strike,” she said.

The union had planned to challenge the hotel’s noise measurements in court.

But Justice Nigel Kent told union lawyers it seemed clear they would likely lose, given the precedent set in 2019 when three downtown hotels obtained an injunction over a Unite Here campaign of creating extreme noise.

“All this is window dressing to allow you to get in front of me today to get the injunction that you hope is going to add another arrow in your quiver in this labour war that’s going on,” Kent said.

At 11:15 a.m. — the scheduled break for the court clerk — Kent advised the parties to find a resolution before they returned. When they met again, they had reached an agreement for the union to voluntarily keep their noise down to a legal limit.

Travis said the noise on the picket lines isn’t intended to be bothersome to people nearby.

“I think the employer would like to have a very depressing picket line where people have no energy and they feel discouraged and afraid to be there,” Travis said.

Not afraid to strike

The union is nothing if not busy.

Besides the Sheraton, its members at the Radisson Blu airport hotel in Richmond have been on strike for two years — the longest in Canada.

And it represents a number of staff who feed and house oil and gas workers at work camps in northern B.C. Workers at one camp recently voted to ratify a contract that included a raise of between 30 and 40 per cent in the first year; workers at another camp got a one-year contract including a 10-per-cent raise, according to the union.

Travis said there has been a “perfect storm” for the hospitality industry.

Business nosedived in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Arnould, who works as a barista in the Sheraton’s Starbucks, was laid off for 20 months. But many staff kept working throughout, she said, attending to travellers who were required by law to quarantine as well as refugees. Many were expecting — or hoping — for a pay increase in recognition of that.

“I’m in a two-bedroom apartment with three people and I’m still spending half my monthly income just on rent and utilities alone,” Arnould said. “So me, I’m looking at my future in this hotel, and how do I have one if I’m stuck in this older apartment for the rest of my life?”

Travis said many hotels in Metro Vancouver have moved to cut or suppress wages, even though the tourism industry has largely recovered. She says employers did the same thing in the wake of other travel slowdowns in 2001, after the 9/11 terror attacks, and in 2008 during the Great Recession.

“There’s this perfect storm where the industries we’re dealing with are doing very well. They’ve recovered, and workers haven’t,” Travis said.

For many, the situation is dire.

Kaushal, who has worked at the Sheraton for 19 years, said she’s finding it hard to pay bills. “I’m a single mom. My son also works here. And I have a daughter who is in Grade 12. So it’s a struggle because there’s two incomes of ours that are not full potential right now,” she said.

The union has a strike fund it uses to pay picketers. But recently, it’s issued public calls for donations. It wouldn’t say how much members receive in strike pay.

At the airport Sheraton in Richmond, Arnould said some lower-wage employees were actually making about as much from those strike fund payments as they would on the job.

But some have begun looking for other work.

At the Radisson Blu, where a strike has continued for two years, virtually all the workers on the picket line have taken jobs elsewhere to make ends meet.

Union members at that hotel say they stay on the picket line because they want to reclaim jobs that some of them worked for more than a decade before they were terminated. Others say they want to ensure a better wage standard at that hotel in the future.

But Sukhi Rai, the president of the consortium that owns the Radisson Blu in Richmond, has argued otherwise. He said in a previous interview with The Tyee that the union mislead the public when it said he had attempted to roll back wages at the hotel before the strike began in 2021.

Last month his company filed a defamation lawsuit against Unite Here Local 40. They say the union has falsely claimed the hotel discriminates on the base of race or sex and that it mistreats its employees.

Travis said the union plans to respond with an anti-SLAPP application, a defence that seeks to bar lawsuits that are filed for the purpose of silencing people or organizations.

She says the union doesn’t look for fights. But when it has them, it fights hard.

Unite Here Local 40 is a regular at the BC Labour Relations Board, where it tries to catch employers breaking laws. This summer it successfully proved the Radisson Blu, for example, had broken replacement workers laws during the strike at that hotel.

At the Sheraton, the union won the right to also picket two adjoining hotels, boosting its leverage over Larco Hospitality, which owns all three businesses. Since that picket began, the union says a number of airlines have stopped using those hotels to house their flight crews during overnight stays. The picket also means that other union workers — like mail delivery workers — aren’t reporting to those hotels.

The union also maintains a strong social media presence and communicates regularly with the media — something many unions don’t do.

“We want to shine a light on what’s happening,” Travis said. Travis, who previously worked at the union’s headquarters in New York, says she learned there the importance of media engagement and public pressure.

“Sometimes the media is only interested in the day you issue the strike vote and the day you reach the settlement. Sometimes the story in between there gets lost,” she continued.

The strike at the Sheraton drags on. Workers have been on the picket line for more than 60 days.

But Perry says they plan to see it through to the bitter end.

“If the people on the management side were making the wages we were making and working the jobs we were, they would see why people are so frustrated,” Perry said. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Labour + Industry

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: