There’s an eerie quiet as Stephanie Vaillancourt drives around Yellowknife this week. The pretty northern city on the shore of Great Slave Lake is normally a busy gateway to the Northwest Territories for government workers, miners, doctors and nurses, scientists, journalists and tourists.

Last week, 95 per cent of the city’s population left as multiple wildfires menaced the capital city of 22,000 people.

Vaillancourt is one of 1,600 people who stayed behind. The commercial fisher was initially worried about leaving her inventory of fish to spoil, and confident she could leave by boat if the worst happened.

But after a few days with “a lot of time on your hands,” Vaillancourt joined a crew of volunteers working to build firebreaks around the town. Her team has focused on cutting trees to make a clear path for water lines.

“It’s definitely quiet. It has a bit of an ‘end of the world’ feeling, like a sort of apocalyptic movie where everybody’s gone,” said Vaillancourt.

But there’s also a feeling of community, and people pulling together to protect their town.

“It’s just been a great moment of watching all these people coming together for a common goal.”

From 1,000 kilometres away in Edmonton, Paul Kelly and his family are waiting to hear when they can return to their home. Kelly, along with his wife, daughter and a co-worker who needed a ride, left Yellowknife at 3 a.m. on Aug. 17, the morning after the evacuation of the entire city had been ordered.

On their 15-hour journey to Edmonton, Kelly passed through the town of Enterprise, a small town that had been decimated by a wildfire just days earlier.

“At the time it was kind of hard to process because you’re driving and trying to think of where you need to go, but you’re thinking, ‘This is so weird to see,’” Kelly said of the town he remembers surrounded by green forest with homes and small businesses lining the highway. Now, entire parts are simply gone, and the forest floor is scorched and black.

“It’s not something you think is going to happen in your lifetime or to you.”

Canadian communities are increasingly experiencing fast-moving wildfires that lead to entire cities and towns being displaced, often with little advance warning.

In 2016, a fire tore through the northern Alberta oil town of Fort McMurray. While an initial evacuation order covered several neighbourhoods, the order was extended to the entire city of 66,000 just a few hours later as the fire blocked a key road out of the town. Video taken by residents fleeing the town showed trees fully engulfed in flame on the sides of the highway as ash rained from the sky; two people died in a car crash during the evacuation.

In 2021, a wildfire levelled the town of Lytton, B.C., in just hours with no warning, leaving residents to knock on neighbours’ doors to tell them to get out, then watch as their entire town burned. Two people died in the fire.

A horrifying example of just how fast fire can move when conditions are right happened this month in Lahaina, Hawaii, when residents had no warning and many did not escape a fast-moving grass fire that whipped across their municipality. The death toll is currently at 115, but will likely rise as the town continues to be searched.

Yellowknife residents got more advance notice of the need to evacuate. While the city’s mayor told the public on Aug. 15 that the fire was not a danger to the city, an evacuation order for the entire town was made on the evening of Aug. 16 as the fire travelled five kilometres closer to the city. The closest fire was still 15 kilometres away, but Yellowknife has just one road leading out of the city. (At a Monday update, wildfire information officer Mike Westwick said the fire remains 15 kilometres from the city, thanks to the efforts of firefighters.)

Residents were told they needed to be out of the city by noon on Aug. 18. In the days after the evacuation order was issued, a long line of cars and trucks inched along the highway and lines to fly out snaked around a high school. The Canadian Armed Forces arrived to help get people out, and the federal government contracted extra aircraft.

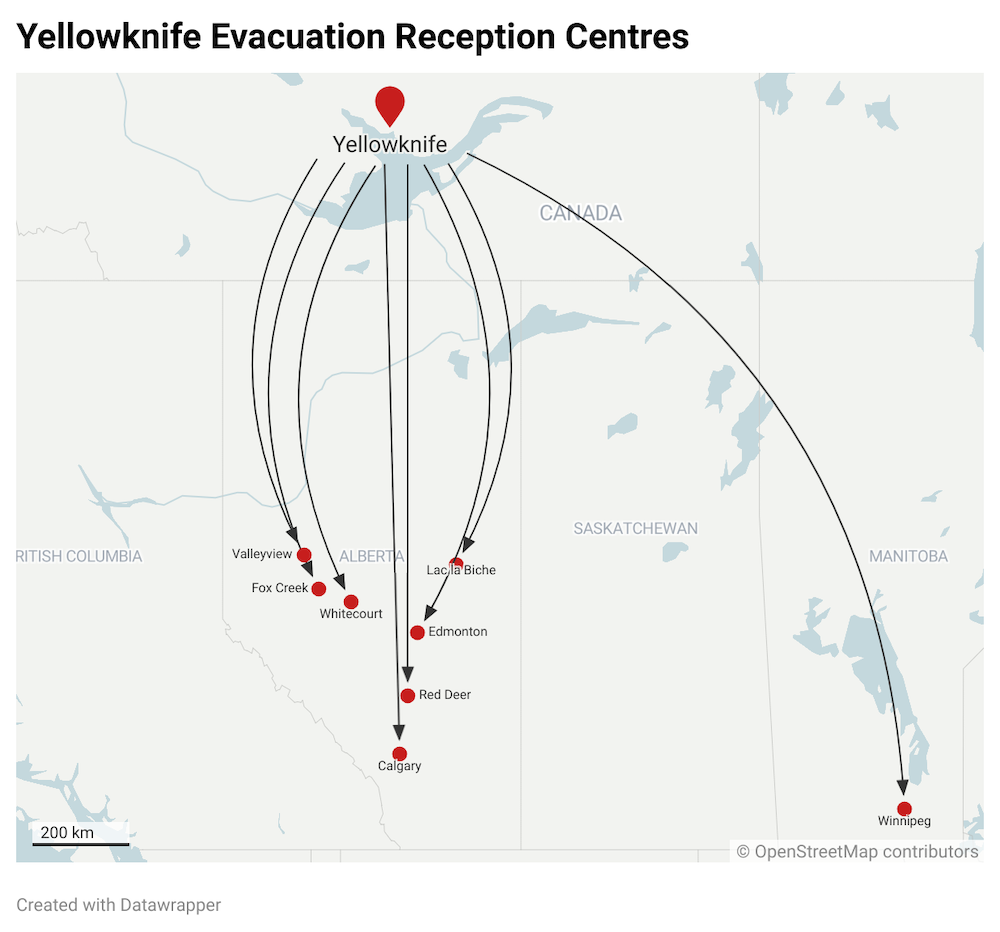

Prisoners had to be relocated to Alberta and fragile patients were transferred hundreds of kilometres to other hospitals. Yellowknife residents are now scattered across Western Canada in several communities across Alberta all the way to Winnipeg, with some hospital patients also landing in Vancouver. Others have travelled further to stay with family or friends.

Residents are being told to register at evacuation centres that have been set up in several towns in Alberta as well as Winnipeg, and have been told they are eligible to receive $750 through the Evacuee Income Disruption Support program if their employment has been interrupted for at least seven days. The territorial government is still scrambling to respond to requests for more extensive financial assistance.

There are concerns about the impact of the evacuation on vulnerable people: Dené actor Melaw Nakehk’o wrote on Twitter that she was concerned about the state of an Elder she found in a Calgary hotel room who had waited in line for 20 hours for a flight out of Yellowknife. (Nakehk’o did not respond to a request for an interview.) Premier Caroline Cochrane told CTV News about searching through Yellowknife the day before the evacuation deadline for any homeless people who may have been left behind. And health-care workers have also warned about overdose risk for people who use drugs or are in recovery.

Yellowknife’s remote location and limited road access make the territorial capital particularly vulnerable to wildfire, said John Clague, a professor of Earth sciences at Simon Fraser University.

“Yellowknife’s a great example of a threatened community because there is only one road,” he said.

“In a lot of these communities that are threatened by wildfires, there is only one road. And if the fire severs that road, you have all these people that are essentially trapped.”

Author John Vaillant spent several years researching wildfires for his recent book Fire Weather: A True Story from a Hotter World, using Fort McMurray as one case study. Vaillant has been urging community leaders, residents and government officials to realize that because of the changing climate, fires in the 21st century behave differently than in the past: they burn more intensely, and can move much more quickly. Defences like building fireguards and setting up sprinkler systems don’t always work: sometimes the only way to protect people is to move them out.

“This isn't gonna go away,” said Clague. “I don't know that every year is gonna be as bad as this one — this one is off scale in terms of the amount of forestland that's been burned and the cost of dealing with these fires is off the scale too.

“But on average, probabilistically, we're going to see more and more of this. There needs to be way more discussion in communities that are particularly at risk.”

Fires in the boreal forest

At a press conference on Monday, Westwick said it could be weeks before Yellowknife residents are allowed to return to their homes, because firefighting work continues. Smaller communities in the territory are also threatened and have been evacuated: around 63 per cent of the territory’s total population is currently displaced.

“The forest that we're dealing with is extremely powerful,” Westwick said.

“That is fire in the environment in the boreal forest, where fire wants to exist, and we're trying to push back against that. And that's tough, because that fire wants to be there.”

While some rain did fall through the weekend, the area is now expecting another stretch of hot, dry weather, meaning the fight to slow the path of the fires will continue.

The boreal is a 2.7-million-square-kilometre forest that stretches across northern Canada from the Yukon to Newfoundland, and the fire season in the boreal has been intense and destructive this year. Earlier in the summer, smoke from fires burning in northern Quebec blanketed cities like New York and Washington, D.C., a wake-up call that wildfires don’t just affect remote communities.

Ellen Whitman, a forest fire research scientist with Natural Resources Canada, said the fires that currently threaten Yellowknife have been burning since June, creeping closer and closer to populated areas.

“Yellowknife is kind of surrounded on all sides of fires at the moment,” Whitman said.

“In terms of the growth over time, the fire has had pretty extreme weather conditions that it’s been burning under.”

Those weather conditions include a drought that has left forest fuel, like branches and dead trees, extremely dry and ready to burn. At times, wind has fanned the flames and pushed the fire. And while there has been a disinformation trend to blame increasing wildfires on arson, not climate change, Whitman says there is no doubt that warming temperatures are playing a big role in 2023’s terrible wildfire season.

When temperatures rise, Whitman explained, forest fuel — the dry wood, brush and other flammable matter lying on the forest floor — becomes dryer, making it more likely to burn. Warmer air can hold more moisture, but it can also draw moisture out of material like dead wood.

“In Canada, we've already experienced [one] degree of warming and in places like the north, it's warming substantially faster,” Whitman said. “There's a lot of variability, but we haven't had an increase in rain throughout Canada across the landscape to compensate for that.”

Fires in the boreal often grow to be very large because northern forests are more likely to be uninterrupted by roads and towns, and fires are less likely to be spotted immediately in remote locations.

A rainbow in the smoke

It’s easy to feel defeated in the face of dire warnings and huge fires. But Vaillancourt and Kelly are focused on the future of their community.

Out on the firebreak, crews are celebrating the small wins, like the cooler, wetter weather that arrived on the weekend, or the break in wildfire smoke that brought blue skies and even a rainbow.

“We’re not out of trouble yet, but it’s one more thing — it’s like yes, we scored one more point,” Vaillancourt said of the short-lived rain. “We’re just trying to win as many battles as we can to win this war.”

She wants people to know how important it is to “firesmart” their homes, referring to work residents can do to move flammable materials away from the sides of their homes and replace landscaping and building features with fire-resistant material. Under FireSmart BC programs, communities also remove fuel from forested areas near homes and businesses.

Kelly said he and his family love living in Yellowknife: it’s a community full of people from every walk of life and all over the world.

“Even now in Yellowknife, there are tons of people who have volunteered, people working as essential workers or contractors,”

“I’m very certain if you polled people from Yellowknife and asked them to come back to do any job… I’m quite sure the vast majority of the people would sign up without hesitation.”

With files from Amanda Follett Hosgood and Jacob Boon. ![]()

Read more: Politics, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: