In 2018, Talin Vartanian, a longtime CBC Radio producer then working on The Sunday Edition, organized an advisory session for temporary employees alongside two producers whom she had taken under her wing as temps.

Vartanian, who had worked for CBC in precarious roles for 20 years before securing permanent employment, knew that temp work at the public broadcaster was a persistent issue many suffered through in silence for decades. So with a few representatives — and some refreshments — from the Canadian Media Guild present, about 80 people gathered in a large, glass-walled meeting room on the third floor of CBC’s downtown Toronto headquarters.

Arman Aghbali remembers being somewhat skeptical that day. In his four years as a temp at CBC, he had navigated his employment situation largely on his own. While he had occasional interactions with union representatives, he didn’t feel as though he’d developed any meaningful connection with the Canadian Media Guild, or CMG.

Aghbali says he immediately sensed that there was “a fundamental misunderstanding about the situation.” A union representative opened the meeting by recounting their own experience as a temp when it was the norm to “stack the contracts” they received until reaching 18 months of continuous employment in a single position, at which point the corporation, under the collective agreement, was mandated to make their position permanent.

But the same conditions didn’t apply to Aghbali and many other temps like him. In fact, they rarely received formal written contracts, as CBC is not required to provide contracts to temps hired for fewer than 13 weeks. Emotions ran high, Aghbali recalls, as he and other temp workers began to voice their experiences. “I was basically just told, ‘Here’s a week, here’s five days, here’s two months.’”

In his four years of temp work, he remembers signing two contracts. Most often, a manager, scheduler or senior producer would ask him to come in for a shift, and he would fill out a time card to log his hours at the end of the week. Given the lack of consistent paperwork and constantly changing positions, he and many of his peers found it challenging to compile and present their employment history in any coherent manner to advocate for a permanent job. The information session, says Aghbali, “felt very out of touch,” because many of the union representatives had built their careers at a time when they regularly received contracts.

The session spurred conversations and a growing sense of solidarity among the current generation of temp workers. “There was just a sudden moment of reckoning, where everyone suddenly realized things are so much different than they had been,” Aghbali remembers. “That was the moment where I feel like a lot of us committed to keep an eye on this and alleviate things where we could.”

They kept talking, and soon after, they started organizing. Though they had some union support, it was clear to many of the temps that day that they would have to advocate for themselves. They wanted to be nimble and focused on their advocacy without tying themselves explicitly to CMG’s bureaucratic structure.

But in an institution that employs thousands, it was difficult to predict how much change could really be made by a loosely organized collective of past and present precarious workers. However, with the collective agreement between CBC and CMG set to be renegotiated this year, there has never been a better time for them to try.

Over 2,000 temps across the country

On any given day, CBC employs over 2,000 temporary and contract workers across Canada. Informally known as “temps,” they are shifted week by week, month by month, year after year, to produce hundreds of interviews and articles.

In return, these temps — who comprise over a quarter of the public broadcaster’s total workforce — are compensated the same as any other employee, with one notable exception. Most are always looking over the edge into unemployment, with no guarantee of ever securing a permanent job.

I was one such temp in summer 2021. After interning for CBC’s As It Happens, I worked as an associate producer for several weeks, filling in for team members who had taken time off. It was during this time when a co-worker suggested I attend a Know Your Rights session for temps, to help me navigate my time at the institution.

And so, one evening in June 2022, I logged onto Google Meet after work and listened as representatives from CMG, the union that represents CBC’s English-language employees, talked to us about our rights as temp workers — from securing health benefits to refusing work when offered — and counselled us about our respective situations. Some were concerned about losing or not getting health benefits if they didn’t work continuously for long enough. Some described never being onboarded properly, and the fatigue of having to prove themselves every time they filled in at a new program. One recounted how switching units had caused them to lose the chance to be converted into a permanent employee.

All sounded exhausted, and seemed to ask the implicit question: How long did they have to keep fighting to prove they belonged at CBC — and that they deserved as much job security and respect as everyone else?

I was torn. There I was, bright-eyed and eager to work alongside journalists I had admired and respected for most of my life. I took pride in being a part of CBC and furthering its mission of serving Canadians. And I know how much its work had meant to my family, who immigrated to Canada in the 1990s. But hearing those stories from my co-workers gave me pause. My experience had been positive thus far, but now I had to consider whether I would still feel the same way after months or years of precarious work.

Demoralized

In 2019, Simon Houpt wrote in the Globe and Mail that current and former non-permanent employees at CBC were “passionate about the broadcaster and its mission, but demoralized over their treatment.” Many of the issues described then persist today: lack of job security still leads to anxiety and poor mental health, poor or insufficient feedback contributes to a constant state of self-doubt over whether one is good enough for the job, and insufficient recognition and appreciation reinforce a feeling of being undervalued.

“I didn’t feel supported by the union at all,” one former temporary employee says. “I felt like they don’t see casuals as their responsibility, even though they make up a huge chunk of CBC’s staff.”

Since that revelatory 2018 information session, a growing number of current and former temp workers have been advocating for CBC to improve its relationship with its most vulnerable employees. Aghbali, whose eyes were opened at the meeting, had been a temp since the summer of 2015. He was one of the lucky ones. After working on the now-defunct “trending” desk for digital news, Day 6, Podcast Playlist and Metro Morning, he finally secured a permanent position at Tapestry in late 2019.

But this is not the norm for temps, and Julian Uzielli knows it. Uzielli temped at CBC for three years before securing a permanent position as an associate producer at Podcast Playlist in 2018, a few weeks before the momentous session Aghbali attended. While he was no longer a temp himself, most of the co-workers he was close to still were, so he still felt personally invested in the issue. He describes that day as a watershed moment. “For many of us, it was the first time we heard our peers express the same frustrations we had,” he says. Suddenly, they weren’t suffering alone anymore. “Everybody was galvanized by that.”

It was clear to Uzielli and several others in the room that something had to be done. It was a small group, with only a core team of five to 10 people when they began. While they didn’t quite know where to start, they were all passionate about securing better supports and working conditions for temps. But they also knew that many temps, concerned that their career prospects could be harmed, were reluctant to advocate for themselves. So Uzielli — now “safe” with his new permanent job — decided to step up and take on the cause alongside Aghbali and a few others. In July 2019, Uzielli was elected director for new members (now director for new members and precarious workers) for CBC’s Toronto branch of the union, in which capacity he would formally advocate for the interests of temporary workers.

For him, the fight was as personal as it was political. After graduating from Western University with a master of journalism degree in May 2015, he was asked by his former supervisor at CBC, where he’d completed an internship, whether he could pick up some work. It was a two-week contract. That summer, he applied for a permanent position at CBC Radio’s The Current. He didn’t get the role, but was offered more temporary work to backfill for absent permanent staff, which he took on that September. He was told from the beginning not to expect a full-time job out of it.

The two- to three-month contracts kept coming. Before long, Uzielli found himself at the 15-month mark. One more contract and he would reach 18 months of continuous work in a single role and, per the collective agreement, be converted to the status of permanent employee. Instead, Uzielli recalls, “One day, my boss holds me back after the story meeting and says, ‘I’m so sorry, but we can’t keep you. It’s not your performance. It’s nothing to do with you personally. This is coming from above. I’m not allowed to keep you.’”

“That should not happen,” says Catherine Gregory, the senior director and chief of staff for CBC News, Current Affairs and Local, after being presented with the situation. “Someone should not get close to their 18 months and then be told they’re no longer needed, just because there’s a fear that they will convert. That is not right. And it doesn’t meet our sense of spirit of our collective agreement.”

Gregory acknowledged the importance of allies for temporary employees, whether that be the union or other allies within the organization. And while some cases do become formal grievances, she says there “aren’t many” that they address at the national grievance committee.

Uzielli says that the lack of formal grievances isn’t representative of the experiences temps have. Many people forgo the process, anxious that they won’t get work during the grievance process, or simply because the action isn’t explained thoroughly to them. While a colleague recommended that he approach the union about his situation, Uzielli didn’t want to “rock the boat” and didn’t file a grievance.

“My assumption was,” he says, “if I push back on this in any way, that’s going to endanger my career. So, it’s much better for me if I just smile and nod and grit my teeth.”

Collective action

The situation took its toll on Uzielli. He has struggled with clinical depression for most of his life, and the additional stress caused by his job and employment status pushed him to the brink of a mental-health crisis. Less than a year after beginning work at CBC, he found himself on antidepressants. Ultimately, as frustrated as he was with the development, he felt that he had to accept the situation and move on if he was going to continue to work for the public broadcaster. His former manager introduced him to other show and department heads, and over the next several months he looked for work across a series of other radio shows, including As It Happens and Tapestry, before landing his permanent role at Podcast Playlist.

Upset by how he and his colleagues were treated as temps, Uzielli felt a responsibility to become a vocal member of the grassroots temp collective, especially given the security he now felt he had as a permanent employee. In its early days, Uzielli and other leaders of the collective emphasized educating temporary workers about their labour rights and collaborating with the union to host regular Know Your Rights sessions. Organizers rarely interacted with the union as temps, if at all. As a result, they were largely unaware of their rights and benefits as employees until several months or even years into their time at CBC.

Through the information sessions, the group tried to become better attuned to the current needs of temps, and dedicated time to answering questions about individual situations.

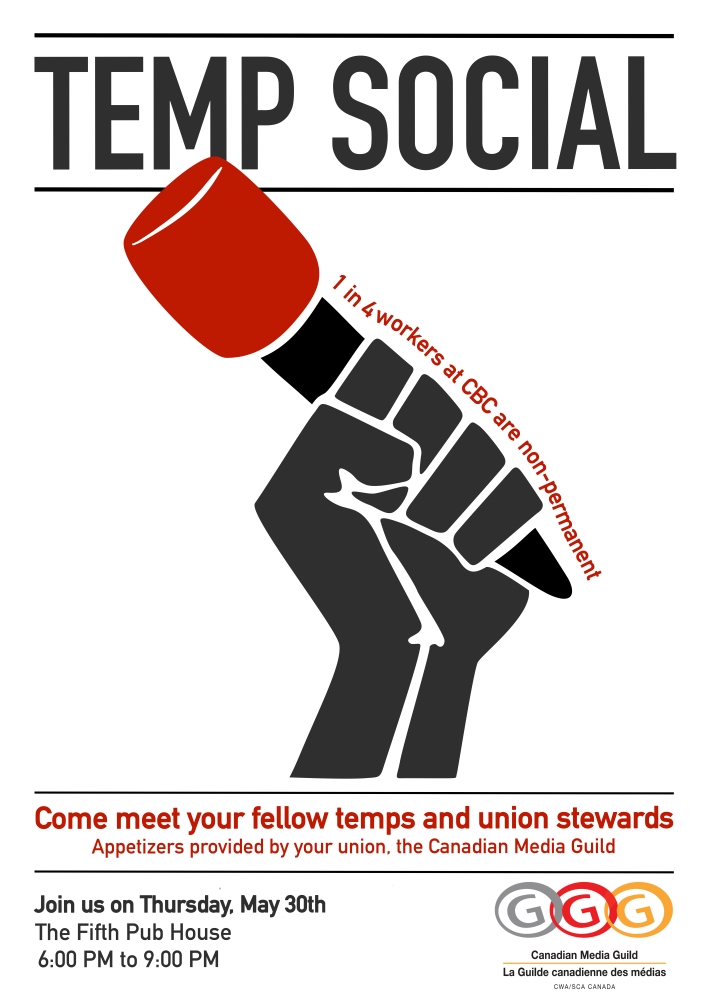

Though the sessions became increasingly popular among temp workers, it was evident to Uzielli that there were some who did not support their initiative. One time, he says, the collective pasted posters on the bulletin boards in the Toronto headquarters to advertise an upcoming Know Your Rights temp social at a nearby pub. But the posters right outside the management offices kept being removed.

“I was just really angry about that,” Uzielli says. “You’re gonna treat us like shit, and then also try and stop us from doing something about it?”

The organizers kept replacing the posters at that spot — putting up more each time — until the event.

The temp collective continued their work throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. In March 2020, those working fewer than 13 consecutive weeks were not eligible for sick leave and benefits, receiving a premium on their earnings instead. The leaders of the collective, wanting change, independently started a petition to institute paid sick days for temps. The petition started getting “tons of signatures” right away, says Uzielli. Within the day, he received a phone call from Kim Trynacity, at the time the CBC branch president of CMG, telling him that CBC had agreed to provide sick days. “It worked,” he says, and so the collective agreed to take the petition down. “We were emboldened to do that kind of stuff.”

In another initiative, Uzielli and a colleague put together a presentation outlining for managers and senior and executive producers what it was like to work as a temp, including factors such as the stress of scheduling and the uneasiness associated with upsetting managers and hosts. They also provided recommendations for hiring and managing temps.

One tangible takeaway was discouraging the practice of giving several workers short-term contracts to “try them out,” as Uzielli and his colleague put it, and instead offering longer-term or permanent work. They also stressed the importance of proper onboarding processes and being as transparent as possible about how much future work temp employees should expect. The anonymous quotes they peppered their seminar with received positive feedback from managers.

Uzielli says, “Some of my own bosses or former bosses would say, ‘This is really eye-opening for me. Thank you for doing this.’”

‘Your life is really pared down to the absolute basics’

The current situation with temp work, Uzielli says, is fundamentally untenable and only serves to hurt CBC in the long term: “It’s creating a crisis of morale.”

In a 2020 open letter co-authored by Uzielli and other members of the temp collective (then formally identified as CMG Toronto Temp Committee) they stated, “Temps are younger and more diverse than their colleagues. They are the very people the corporation needs to retain and promote. But far too often smart, diverse and talented journalists leave CBC in disgust and frustration after years spent spinning their wheels, waiting for job security that never materializes.”

One of those journalists was Meghan (not her real name). Meghan took a job as an online reporter for CBC News in 2015 and, because her hours changed so frequently as a temp, she found it challenging to make plans outside of work. Meghan had previously worked in a permanent position for a regional office at CBC before moving to Toronto to complete a graduate program. After graduation, she worked for one of her professors, but needed more income to make rent in the city. Knowing that the public broadcaster had casual employees around the country, she reached out to her former colleagues and asked about temporary work. “They just basically said, ‘Sure — come in tomorrow,’” she says. “It was very, very quick.”

She recalls feeling excited to work at CBC Toronto headquarters and being “very idealistic” about it, at least early on. She began to pick up shifts quickly, and gradually moved from working part-time to full-time hours. “It wasn’t immediately my only source of income, but then the shifts just kept coming,” she says. “And they always said nice things, more or less.”

Her managers never promised her anything permanent, but she kept getting offered more shifts, which were reliable but not guaranteed. Meghan says she didn’t sign a single contract. Instead, because her hours changed so frequently, she had to wait to see the next two-week schedule to know whether she would have work, and when. Occasionally, a permanent employee would go on leave — that’s when she could feel at ease, knowing she had a full month’s work ahead.

“At first it was fine, but after a while that starts to get stressful,” she says. “And then the shifts were all over the place.”

Working for the main 24-7 news desk, there were shifts around the clock: the early morning shift, the regular day shift, the evening shift and the overnight shift (which no one wanted). It was exhausting. Meghan’s schedule changed so frequently.

“Your life is really pared down to the absolute basics,” she says. “My social life took a real hit. I wasn’t really exercising all that well because you’re just so exhausted.”

After two years, she found herself conflicted. Receiving next to no contact from the union, the only people she felt supported by were other casuals. She started to consider applying to jobs in other fields while retaining her belief in having a place in journalism. Then, when she interviewed for a full-time position, she was told that she had underperformed. She began to realize her heart wasn’t in it anymore. “I just felt like, ‘I don’t think they really respect me enough to give me this job.’”

It wasn’t long before Meghan left for a job in communications. It meant making about $25,000 more a year, and after several years of experience and some specialization, she now makes “close to double” what she earned as a temp at CBC. While there were bright spots in her time at CBC, “There were a lot of things that, ultimately, just broke my heart,” she says. “It’s sad. I hope it’s not like that anymore.”

‘CBC is a vocation’

According to CMG president Carmel Smyth, in 2022 there were up to 1,000 temporary workers across the country working 100,000 hours a month at CBC — providing about as much labour as 625 full-time employees. Similarly, at Radio-Canada in Quebec, more than 1,100 temporary workers work an average of 83,000 hours a month, according to Smyth, who described the situation in a June 2022 CMG blog post as a “two-tiered system where so many are treated unfairly.”

In 2014, ICI Précaires, a collective of about 120 Radio-Canada employees, penned an open letter to denounce how their cause was being forgotten once again amid company layoffs. “I pay my union dues, but have no job security,” they wrote in French. They added they have no insurance and no pension fund. They complained that employees were described as “young” and “up and coming” — even at 40 years old. They were told they had to grit their teeth, that the precariousness was only temporary. And they believed it.

“Two castes eventually emerge,” the letter continued. “Permanent employees who fought for their rights, of course. And me, us, the precarious workers, their children, again and again on the side of the road.”

One CBC employee from Montreal says that many temps feel “jaded,” adding that the lack of stability motivates many casuals to want to leave. But she also recognizes why many decide to stay. “Journalists are weird,” she says. “We’ll do anything for the story, even if it’s not a great situation for our lives.”

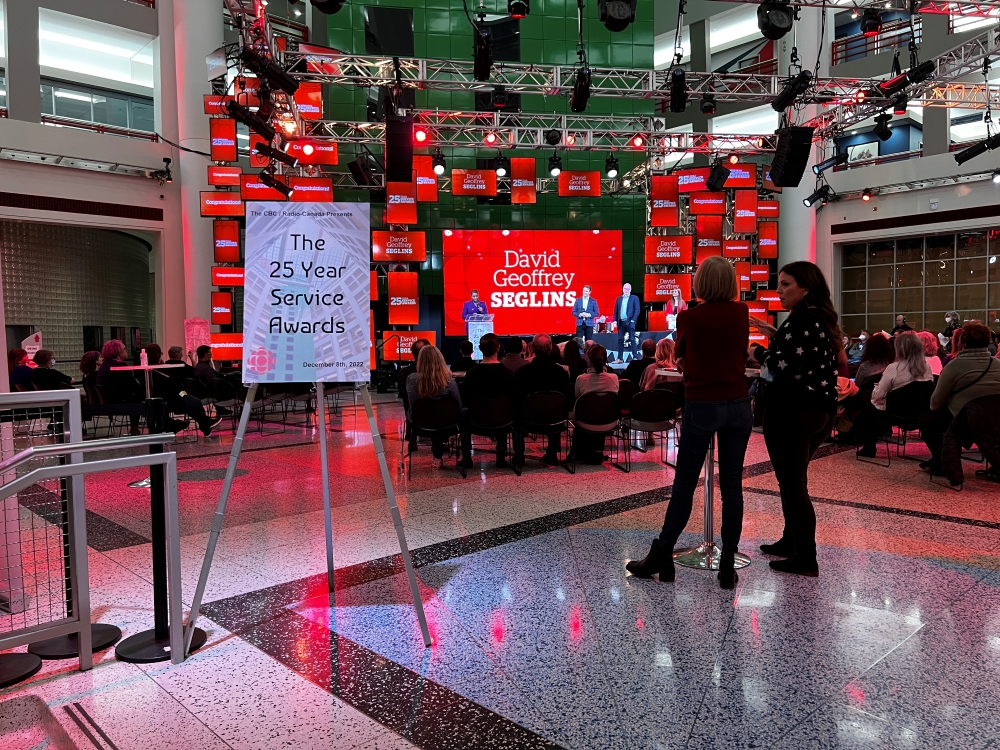

Temporary employees who have worked at CBC for years have also been excluded from service awards and the validation that comes with them. On Dec. 8, 2022, the CMG expressed its disappointment over a lack of recognition for the commitment of temps. That day, CBC honoured employees who had worked for the broadcaster for 25 years. The celebration of their service was rightfully grand. At the Toronto headquarters, the main atrium in the centre of the building was filled with seats. Employees were called onto the stage while CBC editor-in-chief Brodie Fenlon and another senior staff member read a brief biography of each one and mentioned their best work at the corporation.

There was pride and joy in the building that day, but many temps and their allies felt they deserved the same recognition.

In June 2022, CMG had held its own Long Service Awards for 12 of the longest serving CBC temps, many of whom have been temporary for over a decade. They created profiles for each on digital cards showcasing their service to CBC and how their personal lives were affected by work precarity. Among the recipients was Alex Cormier, a father of three from Ottawa who had worked in various technical roles for CBC News over 12 years. Similarly, Edmonton-based Mae Anderson had been working as a French Services contract employee since 2010. Some award recipients raised concerns over issues including financial stability, lack of parental leave and retirement options.

In a post on CMG’s website following the award ceremony, one recipient was quoted as saying, “I was a temp for years; with the union’s help several years ago I became permanent part time. It’s been better since. But this awareness and recognition of temporary workers is long overdue.”

Another added, “CBC is a vocation. In years of working here, I’ve never found any other job I’d like to do. No one does what CBC does. I love it. But after 30 years it’s wearing thin.”

Fear of reprisal

The financial and emotional toll of the precarity of temp work is evident. Less obvious are the harmful effects on those who are already marginalized within the workplace. In the wake of the Jian Ghomeshi scandal in 2014, CBC hired employment lawyer Janice Rubin to conduct a third-party workplace investigation. One of her findings, published in her 2015 summary report, was that younger, non-permanent employees were concerned about establishing their careers, and “were particularly vulnerable which made them unwilling to complain or ‘rock the boat.’”

As an example, Rubin cited a case in which one of Ghomeshi’s relationships was with a young woman in a junior role who — unlike Ghomeshi — was not a permanent employee. In the final recommendation of her report, Rubin reiterated the costs of being “professionally insecure” that many young employees had described and suggested the creation of a joint committee between CBC and CMG to address the issue.

The two parties already have an official committee on the temp issue. Yet, Uzielli says, it’s a reactive group that focuses more on enforcing existing rules than developing ways to improve the status quo. It has no authority, he says, to investigate problems or offer alternative solutions beyond those outlined in the collective agreement.

The hesitation to speak up for fear of reprisal is not confined to the Ghomeshi case. Meghan, for example, outlined a time when a more senior — and permanent — reporter took a story she had published six months before and republished it under his own byline. It was “very nerve-wracking to say anything to your bosses when you know that they could just not call you again,” she says, but she felt that she had to in this case. They asked her not to say anything public about it and promised it would get sorted out internally. Over the next few weeks, she followed up with her manager three times, but was brushed off.

Soon, she was given several shifts in the coveted daytime working hours and a month’s paid vacation. It was what she wanted, but the timing was suspicious. Meghan asked a colleague about it, and when she gave the reporter’s name, the colleague commiserated, telling her that the staff member had been known to have issues with younger female journalists in the past. She never filed a formal grievance, but the way it was handled still upsets her today.

The only racialized person in the room

For racialized reporters, there’s also the added dimension of feeling a need to report on diverse stories while only being casually employed. Samantha (not her real name), a reporter for CBC News in Western Canada, is the only non-white journalist on her team. For a long time, she says, “It felt like I could only report on diverse stories, and those were the only stories that they wanted because they have to fill this diversity quota.” But chasing diversity and building relationships with communities not traditionally represented in media was important to Samantha, so even though she felt she had tried to cover diverse communities in her stories, she also felt like she wasn’t doing enough.

“On top of that, I am a young journalist who is still trying to figure things out,” she continues. “It all comes down to that point of feeling like I have to prove myself every single day, and it can be really exhausting.”

Uzielli recognizes the compound issues many racialized part-timers face. “Temps face all kinds of systemic barriers at work, big and small,” he says. “That’s hard enough for anybody. But if you compound that with the challenges that racialized people, or other kinds of minorities, are already facing, it’s going to show preference to the people who have more ability to get by.”

There are times when Samantha’s identity as the only racialized person in the room becomes more pronounced. One time, she says, there was a stabbing at a school in a more diverse part of town that was often stereotyped as the “ghetto.” Her colleagues rushed to break the story; meanwhile, realizing the scene was her old high school, she began frantically texting family and friends, all the while listening to negative stereotypes about the area from her peers. For everyone else, it was just another task to complete; for her, it was personal. The victim, it turned out, was a friend of her niece (who survived the attack).

Another time, Samantha pitched a story about the local Filipino diaspora marking the 50th anniversary of the declaration of martial law in the Philippines. She knew how important this event was — she had grown up with her parents telling her stories from that period of oppression in the Philippines. Despite her knowledge, she was only asked to cut some clips together for it.

“You’re always having to plead your case,” she says, “having to help people understand that these things are actually important. They don’t have the lens to see it themselves.”

Uzielli says he’s heard many people recount stories like Samantha’s. When temps are in a precarious situation, he says, the priority is maintaining employment over telling the best stories. “If you have a concern about the way your senior producer is framing your story, but you also know that your contract ends next week,” Uzielli says, “maybe you just keep your mouth shut at the story meeting and let them do what they’re going to do.”

This happens even more often, he says, with members from marginalized groups, such as racial and gender minorities, who tend to feel self-conscious about pitching stories about their own communities due to a suspicion that they will be perceived as being biased.

Data gathered by CBC in a 2021 survey of temp workers supports the increased intersectionality that many temps must also reconcile alongside their employment status. Sujata Berry, a former colleague of Uzielli’s at The Current, authored the report and led the internal CBC Temp Project — which, she says “aims to find solutions to improve the working lives of CBC’s temp workers.”

She says that 64.4 per cent of temps surveyed were 35 or younger, compared to just 21.4 per cent of overall staff. Furthermore, the report found that temps are almost twice as racially diverse as permanent workers (35 per cent compared to 19.5 per cent identified as non-white, respectively), with a higher proportion of temps also identifying as LGBTQIA2S+ and persons with disabilities. Over half of those surveyed worked full time.

Despite their years of service, some are denied permanent work. As one survey respondent wrote: “Because of the precarity of my work, I cannot get a loan at the bank or a mortgage, and I must save for a visit to the dentist, or my prescriptions. I work between 180 and 210 days a year here and have for more than five years, yet there’s no indication I will ever have a full-time job.”

“When I talk about my time as a temp, I say CBC is like a bad boyfriend,” wrote another. “They only call when they need you. They don’t think about your needs, but they expect you to show up and be grateful every time they snap their fingers.”

Making progress

Berry is now a producer for CBC Radio One’s White Coat, Black Art, but she began as a temp at CBC 30 years ago this May. She concluded her report with 10 recommendations to better support temporary employees.

This included building stronger mental-health supports, the creation of an ombudsperson position for temps, conceiving solutions for more stable work and developing better connections to job opportunities. Some recommendations, such as an internal job board for short-term assignments and the creation of a website with resources for temps, have already been implemented.

Uzielli says he was “really encouraged” when he heard about the project. It was the first time he felt that management had recognized that this was a problem that needed to be investigated. “I thought Sujata Berry did a really good job,” he says. “It’s a complex, long-standing problem. She tried to be as fair as she could.”

For CBC’s part, Catherine Gregory says that they’ve found some success with the Temp Project, particularly in terms of matching temps with mentors and managers. Gregory also encourages temps to apply for full-time positions, recognizing that a “vast majority” of CBC’s hiring for permanent positions comes from the pool of temporary workers. As of December 2022, Gregory says, there were more than 80 vacancies across the country, but many of the positions received few qualified applications.

Gregory also acknowledged that CBC could improve the timelines for hiring temps. Instead of offering work a few weeks at a time, she says, they’re trying to move to longer contracts, recognizing that gaps in work are likely to arise in the future. This way, she says, “There’s less onus on the temps to always be looking for their next gig.”

Meanwhile, the issue festers. More and more, CMG has been publicly criticizing CBC for its reliance on temps and looks to be primed for a clash with the corporation. The current collective agreement between CBC and CMG will expire on March 31, 2024, which means that renegotiations begin this year. Gregory is less resolute when asked about what CBC’s commitments might be to temps when the talks get underway.

“I can’t tell you yet,” she says. “I am aware that the CMG is interested in this ongoing discussion, and that we hope to be able to engage them in the work that we are doing.”

“There’s definitely more eagerness on both sides to get some progress on this issue, and to make the lives of temps better and more stable and articulate a clear path toward permanent work at the CBC,” says Berry.

Uzielli thinks these talks will be key. “In order for this situation to change,” he says, “the collective agreement needs to change.” Precarious work at CBC was the most contentious issue during the last round of negotiations, and almost resulted in the talks breaking down. Yet, unfortunately for temps, the 2019–24 agreement contained no improvements for them, according to Uzielli. Gregory says that while the language around temporary work in the 2019 collective agreement did not change significantly, CBC and CMG did clarify several aspects, particularly around conversions for those working in the same role for 18 months. The Globe and Mail reported that this also included provisions to convert 41 employees into full-time, permanent roles.

Gregory also noted that since many temps voluntarily work part time due to academic programs or other commitments, it is difficult to state exactly how many want full-time employment. Moreover, some employees choose to remain as temps for the flexibility it provides. A 2020 employment report from CBC stated that while 209 temporary and casual employees in 2019 became permanent in 2020, 25 permanent staff conversely became temporary in that same time frame.

In an email, a spokesperson for CMG drew attention to the guild’s ongoing efforts to fight for jobs and recognition for temporary workers. Uzielli’s message to management is far less equivocal: “By treating people this way for years at a time,” he says, “you’re destroying the morale of the very people that you’re going to be relying on to take this organization forward in the future.”

“The temp system is inherently exclusive and inequitable,” he continues. “It is, by definition, a second class of employee. And how can you claim to care about being inclusive when you are systematically excluding a quarter of your employees, and been doing so for decades?”

Finding solutions

The temp collective continues its work to this day. Last fall, it endorsed three candidates in the election of national CBC branch executives at CMG. All three won, including branch president Naomi Robinson.

In 2023, Arman Aghbali assumed the role of director for new members and precarious workers at CBC’s Toronto branch of the union, the position Uzielli held from 2019 to 2020. The CBC Temp Project relaunched in January 2023, with an expanded range of initiatives to support and develop temporary employees. Berry, who resumed as the project lead in January 2023 for six months, acknowledged the structural challenges at play, but seemed committed to finding solutions.

“The fact of the matter is, we will need a cast of characters — whether they’re permanent or whether they’re temporary — to fill these job vacancies on a temporary basis. The question is, can we do it better?” she says. “We can.”

Uzielli has since taken some steps back from advocacy and has passed on much of his former responsibility to other members. In late 2022 he was promoted from associate producer to producer on Podcast Playlist. When we spoke in late fall, he and his partner were expecting their first child and he subsequently took a few months of parental leave — something he likely would not have been eligible for in his early days as a temp.

“It was a difficult experience, but I don’t blame any one person for it,” he says, taking a moment to reflect on that time. “It’s a system that has evolved into the way it is just through inertia, and it’s hard to turn that ship around.

“I am frustrated,” he continues, “but I know there are people working in good faith to try and make a difference on both sides.” ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Labour + Industry, Media

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: