Last year, then 36-year-old Paul Marlow decided it was time to move out of his mom’s house.

Marlow had lived in Vancouver for more than a decade after college. But he found life in the West Coast city untenable. He acquired more than $60,000 in debt and eventually moved back to his childhood home in 2020.

“Living in Vancouver paycheque to paycheque is impossible with what rent is and what you’re expected to do with your friends — go to Yaletown, and go out and do these things,” the budding entrepreneur and former athlete told The Tyee.

Facing the high cost of living in Vancouver, his prospects working as an SEO specialist and personal trainer, and the tending of his brands — websites focused on mental health and fashion — Marlow decided to broaden his horizons.

In March, he found the perfect location to make his goals come true on a budget.

“Bali just opened up,” Marlow said, noting the cost-effectiveness and climate of the Indonesian island as its most appealing qualities.

For three months, Marlow rented a peaceful one-bedroom villa with a swimming pool in Ubud, a town northeast of Denpasar, Bali’s capital city. A Balinese prepared and delivered healthy meals for him daily, and he often rode a scooter down the town’s narrow roads to a cozy café or co-working space where he connected with fellow migrants.

This all cost him less than $1,200 per month — a stark contrast with his Vancouver expenses, where he spent more than $2,000 each month in rent alone.

After his stint in Bali, Marlow stayed in Lombok — an island east of Bali — for one month, and made a pitstop over the summer in Vancouver. This month, Marlow plans to return to Southeast Asia — first to Bali and then Vietnam. “I want to be able to go around, to hit as many major cities and live there for three to four months at a time.”

Young Canadians like Marlow are taking advantage of the freedom and flexibility remote work offers and moving to lower-cost countries in Southeast Asia and Latin America, where they can afford the lifestyle they increasingly struggle to attain at home.

Across North America, younger generations aspire to live, work and play in hip, character-rich inner-city neighbourhoods where they can walk or cycle to amenities and services. They also seek out meaningful work that allows them to pursue other interests and have a good work-life balance.

But in the face of skyrocketing housing prices and stagnant wages, young Canadians are starting to lose hope about their prospects for the future and are buying into a new narrative of success based on freedom, flexibility and adventure — the three core tenets of digital nomadism.

Looks like I won’t be building my online business’s in my hometown https://t.co/YD5mfJnSSp

— Tall Paul 🦒 (@hitallpaul) June 19, 2022

Defined in 1997 by Tsugio Makimoto and David Manners, digital nomadism is a lifestyle “in which people are freed from constraints of time and location.”

It’s estimated that Canadians represent about four per cent of digital nomads worldwide, surpassed only by travellers from Russia and the United Kingdom — and the United States, which made up more than 50 per cent of digital nomads worldwide in 2020. According to a research brief produced by American workforce management platform MBO Partners, in 2021 there were 15.5 million Americans who identified as digital nomads, a 112-per-cent increase since 2019.

Enabled by digital technology and the privilege of mobility, digital nomads are usually self-employed and do freelance or contract work remotely, usually from a sunny and cost-effective destination. Last year, Statistics Canada estimated that about 40 per cent of jobs in Canada can be done remotely.

According to Beverly Yuen Thompson, an American sociologist and professor who studies contemporary subcultures, the adopters of this lifestyle tend to be young, white, single, middle-income, educated and from countries whose passports allow them to move around hassle-free.

“Digital nomads are very privileged white people from western countries,” she told The Tyee. “They’re positioned socially to be successful, but it’s a struggle even for them to make ends meet in their home countries.”

“They have all these ambitions and hopes about what they can achieve, but the reality is, you have a college degree, you have student debt, and now you can only get a job working in retail. It’s very discouraging, and not the dream that you thought of.”

The squeeze

Thirty-two-year-old Sasha Cooke completed an undergraduate degree in Latin American studies at the University of British Columbia in 2015 but struggled to find meaning in full-time employment after graduation.

For three years she “flip-flopped” between various jobs in Vancouver and Cortes Island. She took on project management, administration and service jobs until 2018, when she decided to go back to school and obtain a graphic design certificate so she could have the flexibility and autonomy she desired.

“I had tried 9-to-5 jobs a couple of times; it didn’t work for me,” Cooke said. “So I knew I had to go back to school for something. Design was a great fit for my interests and my skills.”

With student loans to pay off, Cooke worked long hours as a graphic designer to settle her debt as quickly as possible, but soon grew dissatisfied with the limitations of her position.

“It seems like an impossible dream to be able to afford a home, to be able to afford land as a young person,” Cooke said about her prospects in British Columbia. “You work all day, and if you’re living in Vancouver, forget it, 30 per cent of your income goes in rent.”

Unlike baby boomers, younger generations of Canadians are taking longer — and working harder — to attain middle-class success, says Paul Kershaw, an associate professor at UBC’s school of population and public health and founder of Generation Squeeze.

“They’re studying and working more to have less of the major things that define your standard of living,” he said, like a comfortable place to live.

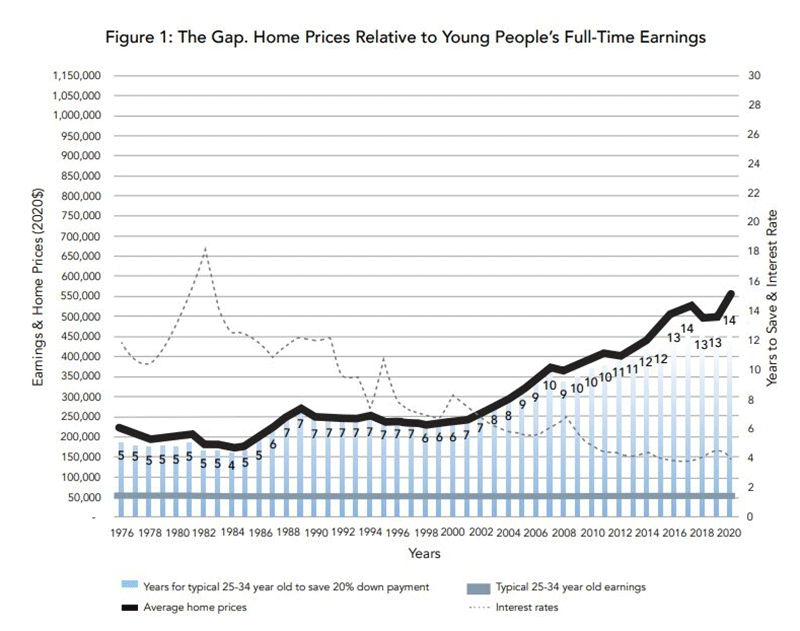

A report produced by Generation Squeeze in 2019 shows that while the income in constant dollars of Canadians under 40 has remained relatively unchanged since the late ’70s, housing prices have more than doubled. The gap between earnings and house prices is at its widest in Vancouver and Toronto.

One of the reasons wages have stagnated is the growing precarity of work, as employers increasingly outsource services to self-employed individuals and freelancers.

“Work is becoming more insecure,” said Nancy Worth, an assistant professor of geography and environmental management at the University of Waterloo. “Rather than full-time permanent benefits, precarious work is the opposite of that.”

This situation seems to be leading to a shift in the values held by Canadians under 40. Because many millennials have only experienced precarious work in their lifetime, Worth says, they’ve reframed precarity as flexibility.

“In some ways we can think about [freelance work] as aspirational,” she said. “There’s stories that we tell ourselves about why we do the work and what motivates us, and the story that each of us tells about our work, and how much or little it connects to who we are and our identity.”

Indeed, young Canadians increasingly aspire to a more meaningful life than a 9-to-5 job can offer, says Matthew Hayes, a professor of sociology at St. Thomas University.

“There are a growing number of people that don’t want that type of life because they’ve become accustomed to the footlooseness of an early adulthood that’s been stretched out by the liberalization of the family and of starting families,” he said.

“So people find themselves still deciding what it is they want to do into their 30s, and a digital nomad lifestyle is a way of claiming that precarity as something that one values and wants.”

Feeling “stuck,” Cooke relocated from Cortes Island in B.C. to Buenos Aires, Argentina, in January, and started living the life she’d yearned for since childhood.

“My dream was always to be a tango dancer,” she said. “So I decided to up and leave and pursue my dream of coming to Argentina and dancing tango.”

Not for everyone

For many, the pandemic’s work-from-home arrangements accelerated a growing trend, further opening up the possibility of “geoarbitrage.”

“Geoarbitrage is the idea that you can locate your day-to-day life in a place where you can basically get more,” Hayes explained, noting that what digital nomads can get isn’t limited to the consumption of material assets, increased leisurely time or work-life balance, but also the privilege that whiteness affords them in some countries.

“[White] people’s bodies may be coded as being more attractive, as appearing younger, more desirable.”

According to Thompson, white, able-bodied and cisgender migrants don’t have to account for factors such as racism and discrimination in their destination country.

“The rhetoric is, ‘anyone can do this,’ but that’s not true at all. They all have strong incomes or passports, they all come from families that can help them out, send them a plane ticket, get them out of trouble,” she said. “If you’re a nomad that’s not a white person, then it’s more complicated — and the rhetoric around that lifestyle doesn’t apply.”

Tired of “living to work” — as opposed to working to live — 37-year-old Adrienne Gross-Leibham, a Calgary personal trainer and digital marketer, took advantage of her remote job as an administrator at a yoga school and moved to Mexico a year ago.

Before 2020, she had been working up to 13 hours a day in a combination of contract gigs and activities: she was a personal trainer at two different gyms, worked the front desk at one of those gyms and did administrative work remotely for a yoga school.

During the pandemic, Gross-Leibham said she “started talking to more and more people that I knew personally in Canada who were leaving.” For her, the possibility of moving to Mexico meant she could support herself but work much less. Overworked and underpaid, she went for it.

“It wasn’t necessarily about having more money,” she said. “It was more like I could still have the same in-out of money flow, but do a lot better things with my free time…. [In Calgary] I had no choice but to work more than full time to make ends meet.”

Both Cooke and Gross-Leibham value the freedom and flexibility remote work has allowed them, especially now that they’re based out of a location where they can get more bang for their buck.

“Coming down here and being able to find something much more affordable, be able to work less and pursue my passion, is a no-brainer for me to stay down here,” Cooke said. In Buenos Aires, she only spends about 10 per cent of her income in rent, even though she now makes half of what she was making in Canada.

“I’m extremely grateful to have the choice to make this life decision.”

A butterfly flaps its wings

While migration affords white Canadians like Marlow, Cooke and Gross-Leibham the privilege of opting out of precarity, digital nomadism has consequences for the residents of the countries nomads relocate to — namely gentrification, displacement and an increased cost of living.

“Most people in the world can’t travel freely and have to work hard at it and prove they have resources and visas and passports,” Thompson said.

By choosing to live in the Global South, digital nomads gentrify neighbourhoods that have been tailored to suit their aspirations and their comparatively high incomes.

In July, the Los Angeles Times reported on the growing tensions between American expats and local residents in Mexico City, a situation that’s hardly unique.

“Corporate landlords know that there are certain spaces that are more desirable precisely because they offer the type of lifestyles that have become popular for certain social classes,” Hayes said.

“It’s very easy for lifestyle marketers to determine what our preferences are and what type of urban areas we would like to live in.”

Privileged migrants tend to be attracted to areas that Hayes characterizes as “meaningful” — walkable, amenity-filled central neighbourhoods with the added value of history and character — a preference that’s being exploited by international financial institutions in the Global South.

“The World Bank plays a really important role in encouraging Latin American governments to see these inner-city neighbourhoods as resources that can be ‘touristified,’” Hayes said. “And digital nomads are playing a role in the valorization of these places because they’re higher income consumers.”

Indeed in May, Cooke was paying $650 for a one-bedroom short-term rental unit in Buenos Aires’s iconic Palermo neighbourhood, where old colonial buildings mix with modern glass towers amidst lush urban parks and tree-lined streets just north of the city’s historical core.

But the ability of migrants like Cooke to pay a higher rate is driving rents up for locals. In July, one third of all short-term rentals in Buenos Aires were concentrated in Palermo. And in the rest of the city, the average rent for a two-bedroom unit has grown by 73 per cent since July 2021, as vacancy rates continue to decline and more housing is switched to short-term rentals. By contrast, a similar unit in Vancouver went up by 19 per cent over the same period.

“A part of me is aware [that] as a foreigner getting paid in dollars, you get to live super well,” Cooke said.

In Bali, on top of affordability, Marlow can enjoy the benefits of being surrounded by like-minded people. “I’ve met a couple people who right away, just after five minutes, are like ‘let’s chat about business and see how we can work with each other, because I need your service or you need my service,’” he said. “I definitely don’t find people that fall in the same line of work with me as well as the same line of mindset in Vancouver.”

But access to Marlow’s community is limited, especially for the locals, says Thompson.

“Digital nomads hang out in expat cafés that are exclusive. Local people can’t afford to enter those spaces. They hide behind a paywall, basically, that local people can’t access.”

Marlow acknowledges that for a Balinese his lifestyle would be nearly impossible to attain.

“I have a hard time at times with [inequality],” Marlow said, explaining that he knows locals can’t afford a cup of espresso every morning, as he does. “If we’re not here, we’re not giving them money at the same time — it’s a weird battle for me.”

Still, Marlow sees his displacement from Canada as less of an outcome of larger conditions and more a matter of personal shortcoming. He feels the decisions he made in his 20s blocked his prospects.

“I don’t want to make excuses that it’s too expensive for people who grew up [in Vancouver]. No, you should have worked a little harder earlier, you should have done your thing — and that’s what I wish I did, so I’m trying to make up for that now.”

Unaffordability follows the nomads

Despite their privilege abroad, young Canadians continue to experience precarious work conditions, as freelance work is unstable and relies on the capacity of the workers to fend for themselves.

Thompson says the freedom and flexibility digital nomadism promises is a delusion. “In the gig economy, you have the freedom to work 24 hours a day, that’s where the gig economy leads,” she said. “And it’s transferring all the risk to the worker, so the worker has all the risk, responsibility, resources [and] they’re not making a survivable wage.”

In Canada, one in 10 workers are part of the gig economy — and most of them make less than $5,000 per year.

While Marlow, Cooke and Gross-Leibham are all able to make ends meet abroad and feel like they’re living up to their aspirations in an upgraded lifestyle, they continue to lack the stability of a job that allows them to take sick days and plan for the future.

It’s “a little bit nerve-wracking,” Marlow says, explaining that his stable clients are startups based in Vancouver and they may not always provide a consistent source of income. This lack of stability is also one of the reasons he’d prefer to remain in a low-cost region.

“If [work] drops down, I want to be in a place where I’m not going to be taking another $3,000 on my line of credit just to be able to afford my rent and food,” Marlow said. “I’d rather just skim by here until I can make up for that.”

This is an advantage Gross-Leibham got to experience firsthand when the Calgary yoga school she had worked at for four years folded as she was moving to Mexico, leaving her briefly unemployed. But as more affluent migrants flood a region, this perk is likely to vanish as costs rise and less affluent, precariously employed migrants have to find another low-cost region.

Kershaw describes unaffordability as a contagion, following capital from places like Canada to new host countries. It keeps spreading because “those who are victims of it are searching for more affordability elsewhere.”

For this reason, the need to fix Canada’s “intergenerational injustice” is pressing, he said.

“Today’s younger population, in addition to facing lower earnings and higher housing costs, has to contribute more of their tax dollars to go towards old age security and medical care for the aging population,” Kershaw said. “This is a terrible intergenerational injustice going on — you’ve got an older demographic extracting an incredible amount of wealth from the housing system, leaving less affordability for their kids and grandchildren.”

In the meantime, Canadians abroad should be mindful about the role they play in reproducing global inequality.

“They think they’re very adventurous and that people back home are not like that and don’t understand them,” Thompson said. “As someone who is interested in the world and wants to travel, you should really want to connect with people and not just be exploiting this situation where you go to a place explicitly because you can be treated better.”

Advocating for the right to housing here and abroad can be a step in the right direction.

“Global forces are transforming cities,” Hayes said. “Urban social movements are pushing back.”

“How do we maintain access for lower- and middle-income people to decent housing in neighbourhoods that are meaningful to people is something that cities in the first world are discussing. The same discussions are taking place in other parts of the world.” ![]()

Read more: Travel, Labour + Industry, Science + Tech

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: