Michael Byers is a professor of international law at the University of British Columbia whose interests extend beyond this planet. He is co-founder of the Outer Space Institute, a global network of scientists, policy experts, engineers, industry leaders and legal scholars working on problems related to humanity’s accelerating push into space.

The kinds of questions they grapple with range from how to manage fast-increasing numbers of satellites to dealing with space debris and how rockets leaving our planet pollute life back home.

Now seemed like a good time to check in with Byers about the OSI, as it hosts the first annual John S. MacDonald Outer Space Lecture on May 25 at UBC, featuring guest speaker Johann-Dietrich “Jan” Wörner, the former director general of the European Space Agency.

Note the middle initial, “S,” in the lecture title: this John MacDonald co-founded, in 1969, MacDonald, Dettwiler and Associates, Canada’s leading space company.

MDA, as it is known today, built the Canadarms for the Space Shuttle and the International Space Station, as well as the RadarSat series of synthetic aperture radar satellites that have patrolled Canada’s Arctic and maritime zones since 1995. MDA is currently building a next generation Canadarm for a multinational space station in orbit around the moon. MacDonald, as Byers mentions in our interview, was an early supporter of the OSI and its inquiries before his death at the age of 83 in December 2019.

Byers and I conducted our interview — a conversation about space that touched on the war in Ukraine, policing the heavens, and, of course, Elon Musk — by email. Three, two, one… launch.

The Tyee: What goes on at the Outer Space Institute?

Michael Byers: Innovative, transdisciplinary research that addresses grand challenges facing humanity in the use and exploration of space. There’s no other body like it anywhere. We break out of disciplinary silos. Often, we’ll bring 10 or 20 world-leading experts, all from different backgrounds, together for several days to discuss a cutting-edge problem. The format is flexible, open-ended. We aim to challenge assumptions that are often taken for granted in building public policy.

I think, for instance, you’ve been looking at what it will mean when we have tens of thousands of new satellites whizzing around Earth.

That’s a good example of what we do. Sometimes, the issues are already known, but the big picture is missing. In these situations, we try to put the pieces of the puzzle together. Last year, we considered the full range of impacts that “mega-constellations” of satellites could have on the environment. These include the cumulative effects of rocket launches depositing black carbon and other substances into the upper atmosphere, as well as, crucially, the changes to atmospheric chemistry that could result from having large numbers of satellites — potentially thousands each year — deorbiting and “burning up” at the end of their short five-to-six-year operational lifetimes.

We do not yet understand all of the processes involved, but we were able to conclude that the adoption of the “consumer electronic products” model for satellite systems imposes risks on all of humanity. One partial solution might be to limit the number of satellites that companies are allowed to launch, thereby incentivizing them to build higher-quality, longer-lasting satellites, rather than tens of thousands of low-cost, mass-produced, short-lived ones.

It seems as if Elon Musk is creating a lot of work for you?

Musk follows the Silicon Valley credo of “move fast and break things.” In addition to their future climate impacts, his thousands of satellites are already creating an existential threat to astronomy through light pollution and radio spectrum interference.

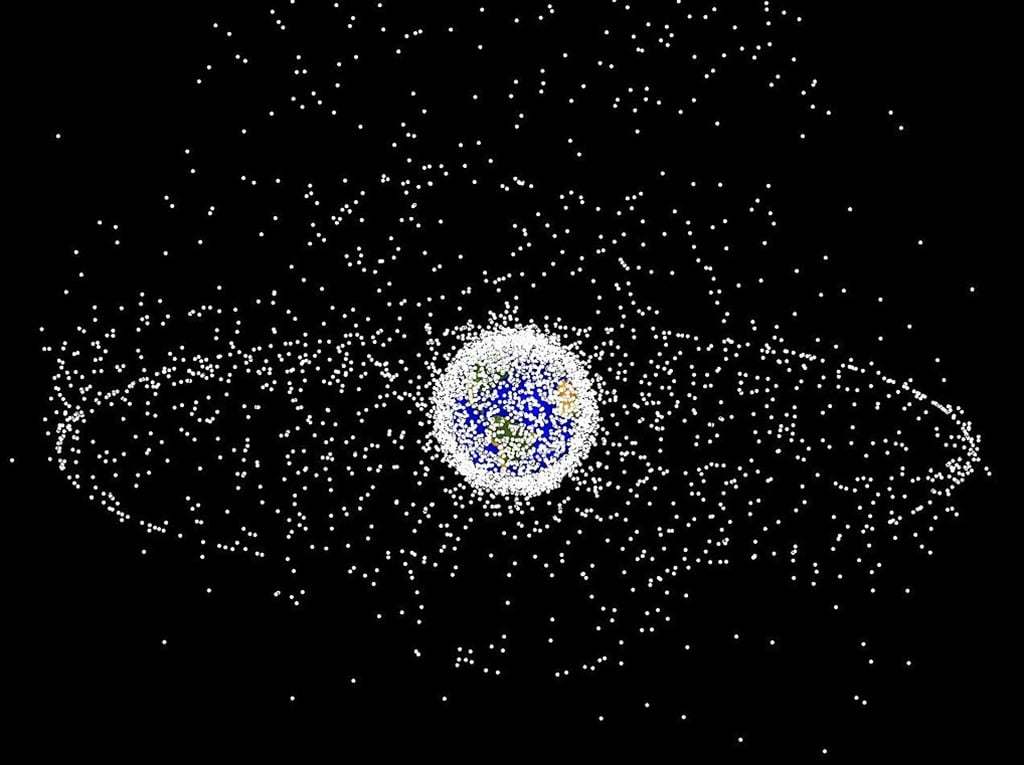

Musk is also contributing to a space debris crisis — in part because he views space as Too Big to Care. In December 2021, he assured the Financial Times that “tens of billions” of satellites could safely be placed in low Earth orbit. That’s a band around the Earth stretching from 100 to 2,000 kilometres above the planet’s surface.

“Space is just extremely enormous, and satellites are very tiny,” Musk said. Orbital shells as shallow as 10 metres could be employed, Musk said, in which case, “A couple of thousand satellites is nothing. It’s like, hey, here’s a couple of thousand of cars on Earth — it’s nothing.”

The comparison might seem to make sense at first glance, with some types of satellites having similar sizes to cars, at least without their solar panels. But cars barely move when compared with satellites, which orbit the Earth every 1.5 to two hours in low Earth orbit. Satellites thus sweep out a large volume each orbit, with lots of potential for collisions. Cars, moreover, are extremely manoeuvrable and can slow down when traffic becomes congested. Satellites can make only minor course corrections, barely changing speed.

Worst of all, there are literally millions of small, undetectable but still lethal pieces of debris and meteoroids to contend with. We know that some of these pieces will likely destroy or disable some of SpaceX’s Starlink satellites — indeed, we can calculate the statistical risk. We also know that that the resulting debris will create a risk of knock-on collisions. Indeed, we’ve already had one major satellite-satellite collision — at a time when low Earth orbit was far less congested than it is today.

Musk is supposed to be a genius. Is he wrong that space is Too Big to Care?

Too Big to Care is a widely held mentality, including among many extremely bright people, because it’s very difficult to understand how humanity interacts with something so foreign, intangible and immense. That’s why we needed to create the OSI — a network of experts from different disciplines who can identify problems and work out solutions together, and do so better than any single person, or any number of experts working in parallel.

It's also important to note that the Starlink satellites do have the potential to make some positive contributions, for example, dramatically improving internet connectivity in remote regions such as the Canadian Arctic.

Most recently, Musk delivered hundreds of portable Starlink ground stations to Kyiv that are now enabling the Ukrainian military to maintain broadband connectivity despite the Russians cutting ground-based cables and hacking or jamming satellites operated by other companies.

As social and natural scientists, we try to assess Musk’s activities objectively: many of them are foolhardy, even dangerous; and yet some of them are good.

Has Putin’s war on Ukraine affected developments in space?

The space governance regime is based on six decades of co-operation between Moscow and Washington that led, first to the creation of the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space in 1958, and then the International Space Station in the 1990s. It is there, on the ISS, that, thankfully, Russian cosmonauts and western astronauts still work side-by-side.

Russia also continues to co-operate with western states in the COSPAS-SARSAT program, which uses a network of more than 70 satellites for the detection and location of activated emergency beacons — on ships, planes, as well as handheld devices — and promptly sends this information to the relevant authority responsible for search and rescue in the territory or maritime zone from which the distress signal is received. If you have such a beacon in your backpack or sailboat, Russia might one day help to save your life.

However, we are seeing the suspension of co-operation on unnecessary or non-urgent matters. The launch of ExoMars, a Mars lander co-developed by Russia and the European Space Agency, has been postponed. Similarly, Russian rockets are no longer being used to support space launches from the European spaceport, located in French Guiana.

I’ve been reading that Ukraine’s military has been aided by other countries helping them to organize their efforts and locate targets. I assume satellites are involved.

The Ukraine War is raising difficult issues concerning the role of satellites in armed conflict, including civilian satellites.

Have SpaceX’s Starlink satellites become a legal target for the Russian military now that they’re being used to provide connectivity to the Ukrainian military?

Or does the fact that the very same satellites are being used to help remote communities in the Canadian Arctic and elsewhere provide them with legal protection? And what about RadarSat-2, which is owned by MDA, the company that John S. MacDonald co-founded, and is now generating high-resolution images for the Ukrainian military — even at night and through clouds? RadarSat-2 is, simultaneously, being used by climate scientists studying the melting of glaciers and the thickness and movement of sea-ice.

One can even ask whether satellites can ever constitute legal targets, at least for weapons such as ground-based missiles that depend on violent strikes, because of the inevitable creation of large amounts of space debris.

In September 2021, building upon growing awareness of the problem, the OSI organized an international open letter that called for the negotiation of a treaty banning the testing of such “kinetic” anti-satellite weapons. Three months later, the United Nations General Assembly created an “Open-Ended Working Group” to study this and other issues of space security. Then, in April 2022, the United States made a so-called “unilateral declaration” — binding itself, through a public statement intended to create a legal obligation, to never test such weapons itself.

In the last few weeks, several countries, including Canada, have made similar declarations. This is just another situation where we can see good developments mixed with bad ones: there’s progress on arms control in space while, at the same time, there’s a war in Ukraine that’s increasingly dependent on satellites.

Yikes. So when people talk about the situation in Ukraine blowing up into a new world war, it’s not far-fetched to imagine a new space war, too. What’s Canada’s role in heading off that kind of space warfare?

Canada’s ambassador to the United Nations, Bob Rae, was very supportive of our campaign for a treaty to prohibit the testing of kinetic ASAT weapons. A good number of former Canadian foreign and defence ministers signed our open letter, along with several retired Canadian astronauts.

But while Canada was the third country in space in 1962, with the launch of the Alouette-I science satellite, it’s not the major player it once was. If Lloyd Axworthy were foreign minister today, you could imagine him convening an international conference on anti-satellite weapons, just like he did for anti-personnel landmines in 1997. Perhaps the OSI can help get Canada back in the game, by raising public awareness of the opportunities and challenges facing humanity in space.

However, the OSI is globally oriented. We’re an international network. We’re publishing in international journals, speaking at international conferences, collaborating with experts from around the world, and interacting with foreign governments, international organizations, space companies and space agencies.

Having Jan Wörner deliver the John S. MacDonald Outer Space Lecture reflects that global orientation. Dr. Wörner led an international organization that supports a huge amount of cutting-edge space science. Like us, he’s committed to peace, the pursuit of knowledge and the sustainable development of space.

So tell us more about Jan Wörner.

Johann-Dietrich “Jan” Wörner was the director general of the European Space Agency, an international organization made up of 22 member states that runs its own spaceport, operates dozens of satellites dedicated to environmental science, explores and studies the solar system by sending robotic probes to other planets, and is a partner in the International Space Station. In short, ESA does lots of good things in space, including by demonstrating that countries can get more done, and have a greater positive impact, when they work together.

Dr. Wörner, as a long-time promoter of space collaboration, has had a huge influence internationally.

I should add that when he speaks next week, in the spirit of collaboration, this will not be a standard lecture. After a few initial questions from the moderator, the event will take the form of a Q&A between the audience and Dr. Wörner. We anticipate a wide range of questions, from the central role of satellites in climate change science, to the possibility of life on Mars.

It’s a shame John MacDonald won’t be there to be part of that discussion. He’d have loved it, I’m sure. He’d also be pleased that the lecture is sponsored by MDA.

John was an engineer, academic and entrepreneur — a pioneer in renewable energy as well as space tech. I first met him in 2005, shortly after a solar energy company that he’d co-founded, Day4 Energy, had one of the largest stock market launches in Canadian history.

John was a proud graduate of UBC and a faculty member from 1965 to 1973. Together with Vern Dettwiler, he built a world-leading, high-tech enterprise from scratch, starting in the basement of his home near the campus. John was also a gifted teacher, an inspirational employer and a proud Canadian. He was very encouraging when, in 2018, Aaron Boley and I told him about our plans to establish the Outer Space Institute. His example inspires our work.

If you are interested in attending the first annual John S. MacDonald Outer Space Lecture, delivered by Jan Wörner, here is the ticket information. ![]()

Read more: Science + Tech, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: