Work at British Columbia’s River Forecast Centre is a little like trench warfare, long stretches of waiting followed by heart-racing action.

As a fresh recruit at the forecast centre, Allan Chapman’s first big action occurred only months into the job. In October 2003, an atmospheric river or “pineapple express” slammed into the southwest coast hitting the Sea-to-Sky corridor, Whistler and Pemberton with ferocity.

Nearly 20 years later, his voice still catches when recalling what unfolded. Twelve hundred people were evacuated. Roads were washed out. Hundreds of homes were inundated with water. Four people were killed as their vehicles were swept off the road. And then, several weeks later, a gruesome find added to the death toll when another car was pulled from the once-raging waters of Rutherford Creek and a fifth body was recovered.

“I still get emotional thinking about it,” the retired hydrologist says.

Chapman believed that the River Forecast Centre was inadequately organized to deal with rapidly developing rain-caused floods, and he quickly instituted changes when he was named to head the River Forecast Centre the following year. Between 2004 and 2010 when he ran RFC operations, he issued many warnings for most regions of B.C. that flooding might occur. They included warnings for Vancouver Island, the South Coast and Fraser Valley, the Thompson and Skeena rivers, the community of Grand Forks, and elsewhere.

More than once, he would be commended for his proactive approach to public health and safety by then environment minister Barry Penner.

Among Chapman’s lasting accomplishments was to introduce a new three-stage warning system. Prior to that, the RFC was focused almost entirely on the Fraser and Thompson rivers. There was no hierarchy of warnings. Now, a system of warnings applied across the province.

The warning system remains to this day and consists of “high stream flow advisories,” “flood watches” and “flood warnings.” And Chapman readily discloses that it was not a new idea and was essentially “stolen from the Americans.”

The first advisory is effectively a warning to look out for what may be ahead — and may be likened to encountering a deer crossing sign on the highway. The latter is as serious as it gets. The flooding has begun. Get to high ground.

The newly implemented system of stepped-up warnings was designed to make the RFC’s work “more systematic and professional,” Chapman says, to provide timely warnings to provincial emergency officials so that tragedies like those in Pemberton in 2003 might be avoided or blunted.

The events near Pemberton pale to what has unfolded in southern British Columbia in recent weeks as at least four people were killed, multiple stretches of critical highways were blown out or buried under landslides, sewage and water treatment plants were overrun and shut down, rail lines were cut, houses were swept away or flooded, entire towns evacuated, farming operations heavily damaged with tens of thousands of chickens and hundreds of dairy cows killed, community natural gas supplies severed and dikes breached and blown open at key places. But in its day, what happened near Pemberton was a big deal and left an indelible impression on Chapman.

From the time he became head of the RFC, Chapman said it was his goal to see that no one died in a flood on his watch. He made it clear that if he saw trouble ahead he wouldn’t hesitate to issue the highest level warnings. And he had the full backing of the government department that would kick into gear immediately should such a warning be issued — the then Provincial Emergency Program, now Emergency Management BC.

At the time, the program’s director and manager were respectively Cam Filmer and Jim White. Both made it clear to Chapman that they expected to be woken in the middle of the night if there was a problem. Not calling them, Chapman understood, would be a mistake.

“If I was in charge of giving out Nobel prizes for B.C. public service, those two would get it. They absolutely knew what they needed to do. They knew what the role of PEP was, and they were absolutely committed to fulfilling that role at the highest level,” Chapman recalls.

Preventing avoidable injury or death and limiting damage to property and critical public infrastructure is supposed to be the raison d'être of both the forecast centre and Emergency Management BC. Which leaves Chapman troubled by what happened — or more to the point didn’t happen — at those critical frontline agencies as the rains began to fall with fury on Nov. 13, setting the stage for the unprecedented wave of destruction that descended on B.C.

“There was ample rain forecast information available by Thursday, Nov. 11, that should have triggered the first flood warning that day for the South Coast and for the Coldwater, Tulameen and Similkameen rivers,” Chapman says, emphasizing the words that day.

“Why did the first advisory from the RFC not happen until noon, Saturday? And even then, why was it a very general and lacklustre high streamflow advisory? The warning should have been a flood watch,” Chapman says. “Also, being a Saturday, you have to ask what happened with this information? Did the RFC contact EMBC [Emergency Management BC] directly by phone to relay the information and urgency? Was EMBC already engaged and active? Did EMBC become active with the RFC advisory?”

A ‘quite extraordinary’ amount of water

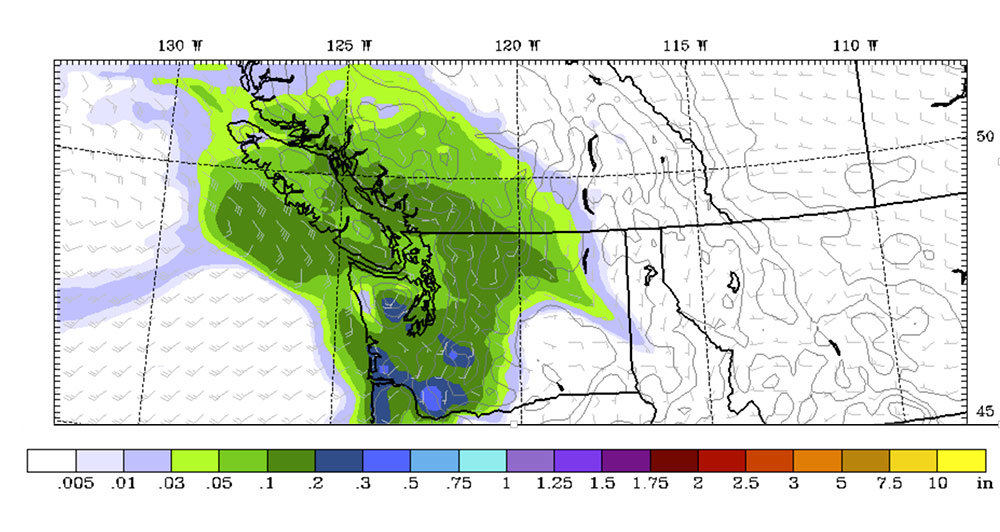

Such questions take on added weight when one considers the information that was available to RFC staff in the critical days leading up to the torrential rains. On any given day, the forecast centre’s five staff have a great deal of data at their fingertips. That information includes the GEM weather forecast model used by Environment Canada as well as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s MM5-NAM and GFS-WRF models. All three models provide detailed projections for 84-hour (3½-day) intervals, and all are generally reliable down to a 12-square-kilometre scale and are constantly updated.

Copious and highly precise hydrometric data for British Columbia and Washington state is also available to the RFC, through an extensive network of stream gauges that measure waterflows in key rivers and tributaries, measurements that are available to public servants at the click of a mouse.

Chapman says his review of the American weather and flood forecast information that was available to RFC staff on Nov. 11 clearly indicated that a major storm was coming. Rain would begin falling Friday, Nov. 10 and carry into Saturday. Then, sometime around 9 p.m. Saturday, “the firehose” would open.

The forecasts showed that by midnight Saturday the rain in the eastern Fraser Valley and east of the Coast Mountains would be falling steadily at a rate of 5 millimetres per hour and that seven hours later on Sunday morning it would be pounding down at rates more than 2 ½ times that. This was clearly not good news for the eastern Fraser Valley and for the communities of Princeton and Merritt.

The forecasts available on Thursday, Nov. 11 predicted that from early Sunday through to 4 a.m. Monday there would “consistently” be between 5 and 12 millimetres of rainfall every hour. That meant that somewhere around 180 millimetres of rain would fall on Sunday. Chapman understood that this was record or near-record 24-hour rainfall and used two words to describe what should have been apparent to anyone at the RFC. A “quite extraordinary” event lay ahead.

Warnings, missed and late

In Chapman’s opinion as a long-time professional hydrologist “there was ample rain forecast information available Thursday that should have triggered the first flood warnings” from the RFC for the South Coast and the Coldwater, Tulameen and Similkameen river systems. The RFC’s mandate, Chapman emphasized, is to forecast. Back casting may be an interesting abstract academic exercise. It’s of no use to people whose homes, livelihoods or, for that matter, whose lives may be at stake.

If the RFC believed that flooding was likely, it had a duty to say so.

Instead, the RFC’s first and mildest advisory came only at noon on Saturday. Not only was that advisory too late given what the forecasts were showing, Chapman said, but it was insufficient given the gravity of the situation. It would take more than a full day after that for the first second-level “flood watch” warning to be issued. But by then, Chapman said, it was too late.

Chapman has concerns about a slew of RFC advisories issued from that point on.

At 5:30 p.m. on Sunday, Nov. 14, the RFC issued flood advisories for the Tulameen River by the community of Princeton and the Coldwater River near Merritt. Chapman said the warning came “very, very late” considering that both rivers “were already well above flood stage,” exceeding 20-year and 50-year highs. “These are very big floods already at this time,” Chapman says. “Why was there such a delay in understanding what was going on with these rivers? What happened with this information? Was EMBC alerted directly, and were the affected communities alerted?”

Similarly, the first flood warning mentioning the Coquihalla Highway was at 6 p.m. Sunday. That warning, too, was “very, very late,” Chapman, said. By then, the available hydrometric data showed the Coquihalla River exceeding the 10-year return period and rising rapidly. “Again,” Chapman asks, “what happened with this information?”

The first flood warning for the Simalkameen River came at 5 a.m. on Monday, Nov. 15. “This is far, far too late,” Chapman says, noting that the river was by then exceeding one in 50-year returns and continuing to rise.

And then, six-and-a-half hours later a flood warning came for the Nicola, a high consequence river near Merritt. “Again, this is far too late to be helpful to the communities affected,” Chapman said, noting that the Nicola at that point was at a 50-year high and rising. “Three hours before this, as we know, the Merritt sewage plant was inundated. And 90 minutes before this advisory Merritt was evacuated.”

Neither ‘exceptional or alarming’?

Very little has been said publicly by either provincial emergency management or river forecast staff about their actions in the days leading up to the floods.

On Saturday, Nov. 20, the Globe and Mail published a detailed account of the devastation unleashed by the floods. The account notes that when the RFC “looked at its modelling for the days before the historic rain, the mere fact that an atmospheric river was on the way wasn’t considered exceptional or alarming.”

The newspaper then quoted from an email sent by Aimée Harper, a senior public affairs officer for Emergency Management BC. In the email, Harper said that no information before EMBC led it to believe that anything out of the ordinary was in the works.

“Leading up to the weekend of Nov. 13-14, 2021, there was no indication that this event was significantly different than the other heavy rainstorm/atmospheric river events that happened this fall season.”

Harper went on to write that “atmospheric rainfall events have a high degree of uncertainty and complexity, making accurate long-term forecasting difficult.” But Chapman notes that “the weather forecasts available on Nov. 11 clearly showed the very heavy and sustained rainfall across the South Coast and pushing over the Coast Mountains into the south Interior beginning Saturday and lasting until Monday. The weather forecasts didn’t change on Friday, Nov. 12 — they were locked in, and they proved to be accurate.”

The Globe and Mail’s account then noted that on Nov. 13, Environment and Climate Change Canada issued a specific warning about the incoming atmospheric river. “A significant atmospheric river event will bring copious amounts of rain and near-record temperatures to the B.C. south coast beginning late this afternoon,” the warning said. The warning came after several forecasts in previous days had told of incoming rain.

Despite this warning, the RFC’s models apparently showed that river levels would be only in the range of one-in-five-year events. In other words, nothing of consequence.

The account leaves Chapman with many questions. What river level models was the RFC using, because they failed to be even remotely close to the epic scale of what unfolded? Why, based on the wealth of forecast data available showing that a significant event was in the offing, did those models not show the potential for serious flooding? Why did Environment and Climate Change Canada only issue its first significant warning about the atmospheric river on Nov. 13, when its counterparts in the U.S. Pacific Northwest had by then issued multiple advisories and warnings dating back as early as Nov. 8?

All of this, Chapman says, cries out for “an external audit or investigation with external reviewers not tied to the B.C. government” to examine the information before key provincial agencies in the days leading up the heavy rains and the actions taken by various professional staff during the unfolding disaster. And a particular focus of that investigation should be the models being used by the RFC to gauge flood risk, models that grossly underestimated the severity of what was coming.

“The quantitative flood forecast tools the RFC is using appear to be wrong, and their use needs to be curtailed until an audit and an external professional review is completed,” Chapman said. “Most of the staff of the River Forecast Centre are professionals registered with Engineers and Geoscientists BC. I don’t think it is out of line to request Engineers and Geoscientists BC to investigate.”

The province ‘has a responsibility’ to tell communities

On six different occasions at a press conference on Monday, Nov. 15, as the scale of the flood’s devastation was setting in, Public Safety Minister Mike Farnworth pointed his finger elsewhere when reporters asked where the provincial government had been as rivers overtopped their banks, rain-saturated mountain slopes gave way, highways became impassable, homes and farms were destroyed, and the first runs on grocery stores and gas stations began.

“Every community is required to have a local emergency plan and deal with local emergency events,” Farnworth asserted.

Farnworth was either not asked or did not volunteer that the provincial government does, indeed, play a critical role at such times. Chapman, who listened closely to Farnworth’s comments, said he was troubled by what he heard.

“He said emergency response is done at the local level, which is untrue. It’s misleading. In my view, it seems to reflect a lack of knowledge as to how his ministry operates,” Chapman said.

For more than two decades, Chapman says, the RFC has been tasked with providing “critical early forecast information” to Emergency Management BC, which is housed in Farnworth’s ministry. EMBC “then has a responsibility to communicate emergency risk to the communities.”

“And then,” Chapman adds, “EMBC is also tasked with providing communities with access to materials, staff and equipment that is needed at the local level to respond to emergencies. In terms of floods, that has typically been sandbag material, machinery like excavators to remove debris or carry material such as rock to shore up eroding banks or dikes.”

Another key action that EMBC performs upon being notified by the RFC of a pending flood is to establish a Provincial Regional Emergency Operation Centre, or PREOC, and regional Emergency Operations Centres, or EOCs, where they are needed. The PREOC and EOC then co-ordinate efforts across government and with local communities so that they can be as effective as possible in their responses, Chapman says.

Imagine, he says, that early warnings had been issued proactively on Thursday, Nov. 11 by the RFC. Imagine that EMBC had become engaged immediately and started the critical work of assisting vulnerable communities to get their emergency response in place and to be prepared for what was coming. As one example, that would have given farmers a lot of time to get their cows out of harm’s way, sparing them the heart-wrenching losses played out over and over again in the Sumas Prairie area.

The PREOC and EOCs also provide vulnerable communities with access to staff from key provincial ministries. In the case of what unfolded in the Fraser Valley where so much devastation occurred, this would include staff from the provincial ministries of health, agriculture, transportation and highways, public safety and others. “All of the critical ministries that have a role in emergency and flood response are supposed to be engaged at the PREOC level,” Chapman said.

All of this, Chapman emphasized, is made possible by early warnings of an imminent disaster; warnings that come from the provincial government.

Underscoring the importance of the provincial government’s role in emergency response, the Union of BC Municipalities, which provides a common voice for local governments, has passed numerous resolutions calling on the province to provide physical and human resources to support emergency response efforts. At least nine such resolutions have been passed since 2013.

In addition, at the UBCM’s most recent annual convention, a resolution was endorsed calling on the UBCM executive to lobby the B.C. government to provide “accurate and more timely community-based information” that could be shared with local governments and their residents “during declared local and provincial states of emergency.”

Waving the flag early

Chapman says the contrast between what happened in Washington state and what happened in B.C. in the days leading up to the floods is stark.

In Washington, the first general warning was issued by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration on Nov. 8. In B.C., the first such warning was five days later.

NOAA issued its first flood watch warning on Wednesday, Nov. 10. BC issued its first on Sunday, Nov. 14.

NOAA then issued the highest-level flood warnings on multiple rivers beginning on Thursday, Nov. 11. The first such warning in B.C. was three days later.

“In my view, the RFC was two to three days late issuing flood watches and flood warnings. The weather forecast data available as of noon Thursday, Nov. 11 clearly showed potentially record amounts of rainfall in the eastern Fraser Valley and Fraser Canyon, and pushing east of the Coast Mountains into Merritt and Princeton headwaters. The delay in warnings until Saturday and Sunday from the RFC created many problems, including public safety and infrastructure risk,” Chapman says.

During Chapman’s time at the RFC, a total of five people worked for the agency including himself, with a supervisor who had responsibility for another department bringing the total complement of staff to 5.5. Eleven years later, that staffing level remains unchanged. The situation is far different in neighbouring Alberta and Washington and Oregon states.

In 2010, those discrepancies were noted in a report: penned by Jim Mattison, a former senior-ranking provincial government employee turned consultant. For years, Mattison had been B.C.’s top water official. As water comptroller for the province, he had intimate knowledge of the workings of the River Forecast Centre and other water-focused departments within the provincial Environment Ministry (the RFC was subsequently transferred to the Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development).

Mattison’s report noted that Alberta, with a landmass almost 300,000 square kilometres smaller than B.C., had 24 people working at its river forecast centre. In the U.S. Pacific Northwest region, with a landmass 200,000 square kilometres smaller than B.C., the corresponding employment level was 16 staff.

Mattison was clear about what he felt was needed.

“The number of working forecasters in the RFC needs to be increased from the current 2 to at least 6 and preferably more,” Mattison wrote. “The forecasters need to be supported by at least 3 more staff with complementary skills in river forecast technology, meteorology, engineering and computer disciplines.” Mattison’s staffing recommendations would bring the total complement of staff in the River Forecast Centre to at least 12, which he said is “the bare minimum needed to meet the criteria of adequate and timely forecasts in a time of changing climate and rapid growth.”

On the issue of the RFCs forecast models, Mattison’s report was particularly critical. In an observation that provides some much-needed context to the claims made to the Globe and Mail that the RFC’s models weren’t showing much to be alarmed about, Mattison said:

“On some rivers, models have been set up by the [RFC] but because of the short response times of the basins during rainfall flood events, limited input data available and the uncertainties in the rainfall forecasts, the models are limited in their ability to provide accurate flow forecasts. They are therefore used to provide assessments for internal use rather than specific forecasts of flows and river levels for public dissemination.”

In other words, they might have some limited use in-house when disasters weren’t imminent, but be of little or no use at all as the mother of all storms approached.

We’ve been here before

When the Nooksack River in northern Washington state overtopped its banks and its floodwaters began to spill north toward the international border on Nov. 13, it amplified problems in the Sumas Prairie area near Abbotsford.

In the following days, mayhem ruled as local residents tried to save their farming operations, the City of Abbotsford issued an evacuation order for the Sumas Prairie region, and the city officials confronted the dangerous prospect of its Barrowtown pump station being knocked out of commission, which would only make the severity of the flooding worse.

Thirteen years earlier, Chapman was heading the RFC when it looked like the Nooksack would overtop and send water Abbotsford’s way, a not unusual event. Work emails that he saved from that time offer a glimpse into what proactive action looks like.

At 11:11 on Jan. 6, 2009, he emailed Cam Filmer, director of the then Provincial Emergency Program, or PEP, to say that a “flood advisory” from NOAA was in effect for the Nooksack, and that it had not yet elevated the risk to a flood watch but might.

He ended the email by asking Filmer whether PEP would be “activating a higher level” of warning or would wait.

It took Filmer six minutes to reply. Filmer said the PEP was “activating to a higher level” and that “full inter-agency/local government conference calls” would happen that same day.

The next day at 7:50 in the morning, Chapman notified a slew of senior officials including Glen Davidson, B.C.’s top water official and water comptroller; Neil Peters, head of the Ministry of Environment’s flood control section and inspector of dikes; Cam Filmer and others “that the Nooksack River at Cedarville went to flood stage overnight” and that it was “rising quickly.”

“There has been record rainfall recorded in the Cascades, and the Northwest River Forecast Center in Portland is forecasting record flood peaks in some areas in northern Washington. There may be implications for flooding into B.C. from the Nooksack today and tomorrow,” Chapman warned.

Because of Filmer’s rapid response to the earlier lower-level warning, emergency co-ordination between PEP and the City of Abbotsford was already underway and a City of Abbotsford official was enroute to Everson, Washington to monitor the river’s climbing water levels in person.

By 12:49 p.m. that same day, Neil Peters requested $5,000 in funds through PEP so that a rapid hydraulic modelling assessment could be done of the Nooksack’s potential overflow. This would assist emergency planners in figuring out who might be most in harm’s way. It would later be estimated that it would take approximately 20 hours for the Nooksack water to reach the Sumas Prairie area.

A little less than an hour later, Peters emailed the list to say that “updated information” he had received from officials working for Whatcom County’s river and flood division in Washington state was that the Nooksack’s overflow was likely to be minimal. Nevertheless, Peters preached caution. This was no time to relax.

“Water levels can also increase due to channel changes at the overflow sites, during the flood event. Hence it is important to continue to monitor the situation until the river levels have subsided,” Peters said.

Over the next couple of days, City of Abbotsford officials and Ministry of Environment officials would both travel to the border area to keep a watchful eye on incoming water. It was going to be a close call.

On Jan. 8 at 10:40 a.m., Art Kastelein, the City of Abbotsford’s manager of drainage and special projects, reported that water was at the underside of the Boundary bridge over the Sumas River. Water was also flowing over the road about 800 metres west of the bridge to a depth of 100 millimetres where it covered a stretch of road 100 metres long.

But the flooding never got much worse.

Shortly after Kastelein’s email, Peters sent an email providing updated information from Whatcom County. The Nooksack’s levels were starting to drop, and while overflow into B.C. was occurring, it was anticipated to stop soon.

“By then,” Chapman says, “Neil was driving out to the border and overflow area to assess conditions himself. Neil subsequently reported by phone shortly after that the Nooksack overflow into B.C. had stopped.”

All of this happened, Chapman says, in response to what turned out to be a minor overflow into B.C. And that’s the key point. A threat was there. It didn’t go unnoticed. It was treated seriously from the start. The provincial government stepped in to assist the vulnerable community of Abbotsford. City and provincial officials alike actually put boots on the ground to assess the risk. And they were ready to act together in the event that things got bad.

If actions like that happened this time out, both Emergency Management BC and the River Forecast Centre aren’t saying. EMBC declined to answer questions filed on Nov. 19 about information it may have received from the RFC and whether the RFC forewarned it on one or more occasions about what lay ahead. It also would not answer questions about when it may have set up its first regional emergency operations centres.

The RFC, meanwhile, declined to answer questions filed with it the same day. Questions included why it issued warnings so much later than its U.S. counterpart, what it may have done with information available from its U.S. counterpart, and when it alerted EMBC about severe flooding risks in Abbotsford, Merritt, Princeton and other areas.

In the face of silence, the flood of questions is certain to grow.

This piece is co-published by The Tyee and the B.C. office of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, where Ben Parfitt is a resource policy analyst. ![]()

Read more: BC Politics, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: