One afternoon late in July, during the province’s second heat wave and as wildfire smoke engulfed Vancouver, Anjali Appadurai was watering the garden crowding her tiny patio. This was going to be her “summer of flowers.”

But now the flowers’ petals were scorched brown from successive heat waves. Appadurai stood upright, breathing the hazy air into her asthmatic lungs. “Something big needs to happen,” she told herself. Her phone rang. It was two friends saying Jody Wilson-Raybould had given up her seat in the Vancouver Granville riding. They thought she should run.

Her answer was “an easy yes,” she recalls.

“Then I realized what I’d signed up for.”

Appadurai didn’t think she would ever run for office. As a longtime climate justice organizer, having watched elected leaders of wealthy countries thwart international negotiations to cut emissions, she decided she would act outside what she saw as an unjust political system.

As an activist, she was known for taking a bold and vocal stance against half measures crafted to broadly appeal by politicians all too expert at the “art of the possible.”

But this summer, what was possible felt different to her. As the pandemic and fires surged, the stakes grew increasingly apparent, and more and more voters seemed to be losing patience. She saw a new role for the elected. “I think there are more people willing to mesh the gears between movements and the electoral system,” she says.

She’s campaigning in a new-ish electoral riding straddling some of the wealthiest properties in B.C. along with a large contingent of young renters struggling to exist in the country’s least affordable city. Vancouver Granville was recently described as an election “bellwether” with voters liable to spring any direction after electing Wilson-Raybould, a Liberal-turned-Independent, in 2019.

She faces Liberal candidate Taleeb Noormohamed, who held a senior position in the federal government and benefits from name recognition by running against Wilson-Raybould in the last election, but drew criticism when his long record of profiting from house flipping surfaced early in this campaign. Other opponents include lawyer Kailin Che for the Conservatives, Coalition Against Bigotry co-founder Imtiaz Popat for the Greens, and computer engineer Damian Jewett for the People’s Party of Canada.

Appadurai’s campaign team quickly grew to 200 volunteers, many of them drawn from activist organizing. “I would sum it up as a beautiful beehive,” says Appadurai. One with digital instincts. The campaign is assembled daily via a Discord server, which she describes as “like Slack, but for gamers.”

In person, Appadurai gives off the confidence of someone who believes she can win but is not afraid to lose. “She looks you in the eyes,” says one supporter.

She is being closely watched by people who share her sense that electoral politics are changing in Canada. Some consider her personable activism (think Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in the United States) a vital asset as people hunger for an alternative to professionalized politicking.

Others do the demographic math in Vancouver Granville and say that in such middle-class areas, too many voters are invested in the status quo to embrace so progressive a candidate. If this is correct, it raises a bigger question. What is the best path for the New Democratic Party to take as Canada faces enormous challenges closing in like a stifling heat dome? Should it be more palatable to the middle, or should it use campaigns like this one to herald a more radical vision of change with the aim of bringing the culture along?

Appadurai was born in the state of Tamil Nadu in southern India. From an early age, she was aware of injustice. She remembers a childhood friend who herded her family’s goats, alone, before the age of six, and another child her age who ate from the garbage bins outside her house. Her family’s middle-class lifestyle meant that she did none of these things. “It just never ever, ever made sense to me,” says Appadurai. “And so I held on to that.”

Appadurai and her family emigrated to B.C.’s Fraser Valley when she was six-years-old. She marvels at her parents’ feat of moving two small children from what she describes as a “deeply collectivist culture,” where grandparents and cousins were always present, to a nuclear family structure in Canada. Her father — a high-ranking engineer in India — took a job at Future Shop to get by. It was worth it to her parents, who believed Canada could offer their children more, a dream held by many diaspora families, notes Appadurai. “There’s this sort of eternal cultural promise of better opportunities.”

Yet as she watched her parents manage to work their way back up the ladder, Appadurai was acutely aware of how tenuous her family’s good fortune was. “There’s this idea that we all have access to this upward class mobility,” she says, “but it’s not true at all.” Her family was one of the lucky ones.

In her Coquitlam high school, she started a global issues club that focused on anti-war campaigns. She laughs remembering bake sales where she and other earnest young members sold homemade gingerbread men with limbs broken off for symbolic effect. “Like, I don’t think kids today….” She laughs again. “It was very different back then.”

Justice, human rights, migrant rights — those were the issues for Appadurai. Why worry about nature when she knew people were suffering? “I had fallen into this very common trap I think for a lot of diaspora kids. You think that climate and the environment are kind of like luxury issues.” It took her a while to realize all were “so inextricably linked.”

At the College of the Atlantic in Maine, one of her professors worked with Greenpeace and was part of a coalition of leaders trying to influence the UN climate convention. Appadurai began joining her meetings. “I was hearing these developing country negotiators, their perspective on climate [and] I realized that it’s really an issue of survival and of colonialism, and of debt, and the legacy of capitalism across the world.”

For Appadurai, problems of housing, the drug supply crisis, the pandemic and climate change were all “failures of a common system, and it’s a deeply broken economic model.”

Ten years ago, Appadurai delivered a speech on behalf of the UN youth constituency at the closing of the UN climate conference in Durban, South Africa. “I speak for more than half of the world’s population. We are the silent majority,” she proclaimed. “There is real ambition in this room, but it is dismissed as radical, deemed not as politically possible.”

“Get it done,” she said. Then, stepping from the podium, she finished by yelling “Equity now!” Older delegates in chairs glanced behind them as a crowd of young activists stood and chanted her exhortation back to her.

The speech went viral. It was played in full on Democracy Now. The New York Times called it “remarkable” and Naomi Klein tweeted that she was a “hero.” But Appadurai insists that she crafted the speech in concert with a team of organizers. She had only found out she would be the one speaking it the day before. “It wasn’t me. It was a whole team effort.

“I was like, 'I’m being used for the right thing right now. And I feel that right now too.'” Now that she’s running for office, that speech is resurfacing. “It’s a full-circle moment,” she says.

Appadurai is inspired by the Sunrise Movement in the U.S., a group advocating for political action around climate change, and progressive candidates including Ocasio-Cortez, the outspokenly socialist member of Congress who backs sweeping Green New Deal legislation. Appadurai is also aware that Wilson-Raybould opted not to run again in Vancouver Granville, calling Parliament a “toxic and ineffective” place to work. Inuk MP Mumilaaq Qaqqaq left politics a month earlier, saying “I don’t belong here.”

“It’s hard when you see good people get into politics and then get treated very badly by the system,” says Appadurai. “The institution’s not ready for them.”

But she believes the more people from activist backgrounds seek election, the more women of colour will be supported as city councillors, MLAs and MPs. “And so we as social movements need to lift our people into these positions.”

Other New Democrats running in B.C. this election who fit that mould include Victoria incumbent Laurel Collins, co-founder of a non-profit that advocates against cities investing in fossil fuels; Vancouver South candidate Sean McQuillan, a Cree-Métis labour activist; and West Vancouver-Sunshine Coast-Sea to Sky Country candidate Avi Lewis, a longtime climate activist who helped frame the Leap Manifesto and the U.S. Green New Deal.

Leah Gazan, the incumbent NDP candidate running in Winnipeg Centre and a member of the Wood Mountain Lakota Nation in Saskatchewan, felt an urgency similar to Appadurai’s when she decided to run in the last election. “I do believe we’re at a critical juncture.” Climate change, growing inequality and the rise of white supremacy prompted her after being asked for at least 10 years to put her name forward. “We need strong voices fighting for human rights right now,” she says.

As a longtime frontline advocate, Gazan sees her campaign as directly connected to the movement that supports her. “It’s the movement that elected me, it was the movement that continues to fund me,” she says. “One of the reasons I ran was because I wanted to take the voices on the ground and bring them inside and have that relationship,” she said. “That’s how we push forward in the House of Commons.”

Appadurai is buoyed by similar support. “I’m not coming into this alone,” she says. “I have people from social movements behind me who are holding me accountable.”

If movement-born politicians are bringing energy to the NDP’s ranks, they also can create tensions. Appadurai has already gone against the grain of the federal party, calling out the provincial NDP for its practices logging old-growth forest in Fairy Creek. While NDP Leader Jagmeet Singh does not oppose the Coastal GasLink pipeline being built in B.C to carry fracked gas against the wishes of some Indigenous leaders, Appadurai is clear in her rejection. “My position on LNG is that it’s not a good investment for the future and is not in line with the NDP’s values.”

On the question of reconciliation with Indigenous nations, Appadurai is unequivocal that it would have to include some form of land back to nations, and it should be part of any plan to address the climate emergency.

Hannah Askew, Sierra Club BC executive director and a longtime colleague and supervisor of Appadurai's, is not surprised by Appadurai’s stances. She watched Appadurai push her own organization to build out a focus on international climate reparations. “She takes a principled stand in whatever context she’s in,” says Askew.

“That’s something that I’m really hungry for in our political process,” Askew adds. “I think people are inspired by that integrity, and that honesty, and I think sometimes our political system punishes that, and she’s just someone who’s not afraid to take those personal risks.

“I feel like in doing that, she’s actually helping restore some faith in the political process overall.”

It’s too easy to sum up the NDP as Canada’s left-wing party. Within that left-tilt lie distinct shades of ideology, and various political calculuses.

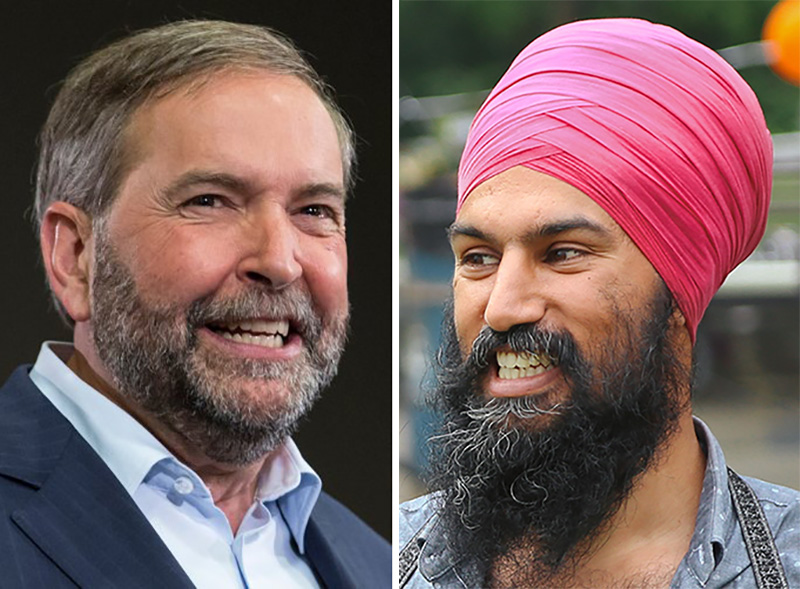

In 2015, Tom Mulcair campaigned as an NDP leader hewing his party towards the centre. Riding high in the polls, he pledged a balanced budget and other “reasonable”-sounding policies, assuming that would solidify his lead, but Trudeau stole it from him by running his Liberals to the left of the New Dems. After that dramatic electoral failure, the NDP paused to regroup.

“After the 2015 loss, people went away and thought long and hard about 'where to next,'” says Katherine Scott, senior researcher at the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. That Jagmeet Singh was elected leader in 2017 signals to Scott that the party wanted to reach out to new communities and constituents. The campaign Singh leads is a far cry from Mulcair’s, harkening to the party’s more progressive past. “This time around, the NDP are obviously on more historical turf,” Scott says.

That turf is exemplified by the NDP’s current platform focus on taxing the wealthy, and on their strong commitments around nationalizing long-term care homes, says Luke Savage, staff writer at Jacobin. “That’s language we haven’t heard from the leadership for quite some time.”

But there are also elements of the NDP’s platform that won’t satisfy more left-leaning voters, who might for example expect the party to build far more social housing faster. Given the urgency of the issue, says Savage, “10-year timelines just don’t make sense.”

And the party not only supports fracking and LNG development, but has been vague about whether it would cancel the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion.

The left-right tug of war within parties is par for the course, says Scott, but she notes that the NDP is unique in its position, balancing strong ties in the labour movement with its other constituents in social movements and progressive communities that are relatively new to politics.

“I actually think the tension can be healthy," she says. “I think that is, you know, fundamentally important in the context of democratic politics.”

The social movements aligned with any party can be “a tremendous source of strength,” but the challenge lies in channelling that force into pragmatic actions that governments can take. “The rhetoric may be revolution, but the tools are reform,” she says. That means encapsulating communities’ climate concerns into a plan to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, for example. “That’s what they’re grappling with all the time.”

Political scientist David Moscrop sees two ideological backgrounds within the federal NDP, one social democratic and the other socialist. The socialists are inclined to discuss worker ownership and nationalization, and the social democrats are more likely to adopt affordability policies like capping cell phone bills.

“There are fundamental contradictions bound up in that,” he says. “And I don’t think [the NDP has] entirely processed that.” It’s a divide that speaks to the ambiguity the party currently finds themselves in.

A key indicator was the party’s decision to remove the reference to socialism from its constitution in 2013. After that, Moscrop says, the party made a concerted effort towards pragmatism. “So their strategy, whether they admit it or not, relies on the Liberals tanking more than the NDP rising, and that’s the goal.”

Moscrop doesn’t see that happening anytime soon, and thinks chances are slim that even a more centrist NDP politics could catapult the party into power. Instead, he’d like to see the party embrace its chance to “set the agenda for fundamental social change.”

“My argument is that the NDP should be expressly socialist, because it would be much better to have a socialist party trying to set the national agenda, and change the way we’re having conversations, and aim for a long-term transformation, than becoming a Liberal-lite party that’s never actually going to form government.”

Savage says polling evidence suggests there is a broader appetite for strong left policies than the party traditionally adopts. “There’s no reason to be afraid of our own shadow,” he says.

In the age of the 24-hour news cycle, says Savage, who ran for the Ontario NDP in the 2014 provincial election, there is a great temptation for political parties’ communications strategists to “come up with language and make sure that it's kind of uniform across the board.”

But it has the paradoxical effect of turning people off. As political messaging becomes shinier and less authentic, people tend to “feel very disconnected from politics, they feel that it’s very removed from them. So they’re less likely to vote, they’re less likely to be engaged.”

One of the best ways to transcend that, says Savage, is for parties to maintain close ties to social movements. “One of the things that can be done to combat that trend is to have more people who come from movements who come from activist backgrounds, or maybe don’t, but just don’t come from the often fairly narrow set of backgrounds that have increasingly sourced political leadership at every level.”

On a recent warm and cloudy Friday morning, a handful of Appadurai’s supporters dot all four corners of Cambie and 12th, waving orange signs at the cars streaming by, and sometimes at one another.

Beth Carlson-Malena, a minister in a non-denominational church in the Mount Pleasant area, uses two hands to steady a banner sign that reads “Anjali 4 Van Gran,” billowing in the wind.

Carlson-Malena had never volunteered for a political campaign before, but when she learned about Appadurai’s climate justice background, it struck a chord. “I was like, oh, my goodness, I need to do more than just vote this time,” she says. “We need to actually work to get her name out there.” According to Carlson-Malena, many other first-time political volunteers felt similarly inspired to campaign for Appadurai.

Carlson-Malena has yet to be at a volunteer event that Appadurai didn’t attend. “She shows up to everything.” Just then Appadurai arrives at the street corner and greets her supporters warmly. Then she runs across the crosswalks to engage with supporters standing at each of the three other corners.

“I just didn’t realize that I would get to meet so many people who are really my neighbours who share similar values with me,” says Carlson-Malena. “No matter what happens, now we get to be connected.”

When asked what she’s working towards, Appadurai doesn’t list climate change, or housing affordability, or many of the issues often quoted at NDP speaking events. Instead, she talks about a different kind of public life, where politics isn’t reserved for the white and the powerful but becomes part of everyday living. She is inspired by Latin American movements like “buen vivir” that encourage participation in everyday politics. It’s something that’s sorely missing from our culture, she thinks.

“We don’t have spaces to gather and to create meaning out of life that’s not just from your nuclear family,” she says. “Where can we gather that’s not a mall?

“I see a stronger public life and strengthened public spaces and institutions and participation in politics — from all of us — and especially from people who are affected by the policies in question.”

Moving from corner to corner at Cambie and 12th, Appadurai mixes with her supporters, speaking with an elderly woman, crouching to smile into the eyes of a child holding his father’s hand, and laughing with a cluster of younger people radiating energy as they wave their signs. As cars flow by, one driver after another honks. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Federal Politics, Election 2021

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: