On a pleasant late Friday afternoon in the summer of 1920, the best baseball players of the amateur city league gathered for a trophy presentation and an exhibition game. A temporary podium was placed atop the pitcher’s mound at the Powell Street Grounds (Oppenheimer Park) in Vancouver. A table draped in a Union Jack held three handsome trophies and a stack of boxes containing medals.

A team posed around the display in the fading light of the gloaming. Stuart Thomson, an English-born, Australian-raised commercial photographer who was a ubiquitous presence at notable events in the city, took a formal portrait with his trusty eight-by-ten Empire State, a view camera with a bellows.

The players wore dark, pinstriped flannels with the city’s name in a vertical stack on a white background along the placket. They also wore scuffed cleats, striped sanitary socks to the knees, and baseball caps weathered by dirt and sweat. One fellow, his shirt opened to his belly and his hand on hip, placed a workingman’s cap on his head at a jaunty angle.

This team was informally known as the Dockers. They were sponsored by the International Longshoremen’s Association and likely have come to the park at the end of a shift on the waterfront. They played an exhibition game against the league’s all-stars, which was called on account of darkness with the score tied at 3-3. There were more important games ahead for the city league champs.

One hundred years ago this weekend, the labour-sponsored Longshoremen battled another amateur team for the Vancouver championship. To history, the Longshoremen’s team is more notable today for the content of their roster than for their success on the baseball diamond.

At a time when professional baseball in the city, as well as throughout Canada and the United States, was segregated by race, the Longshoremen’s roster included a Black player (Ab Mortimer), a member of Squamish Nation (Eddie Nahanee), and a Kanaka, a person of Indigenous Hawaiian ancestry (Herbert “Jumbo” Nahu).

In 1920, the Longshoremen played in a league including the Asahi, a team of Japanese-Canadian players who have been honoured in this century for their athleticism and their role in bridging the racial divides of the 20th century. The story of their rivals, the multiethnic Longshoremen, has yet been told, though the roster encapsulates Vancouver’s history as a port city shared by several cultures and ethnic groups.

A colour line was drawn by organized baseball in the late 19th century, as star player Cap Anson led others in refusing to allow Blacks to play. The line was not codified so much as enforced by a gentleman’s agreement among owners. Whites and Blacks could compete in Mexico and Cuba, or in exhibition games played by barnstorming teams, but Black players were barred from the majors. The restriction would last until the great African-American athlete Jackie Robinson signed with the professional Montreal Royals in 1946, a season before he integrated the major leagues with the Brooklyn Dodgers. Another 12 seasons passed before the Boston Red Sox became the last team to integrate with the signing of Pumpsie Green in 1959.

(The Vancouver artist Bob Krieger, a Tyee contributor and a former editorial cartoonist for the Province newspaper, is painting portraits of each of the athletes to have integrated a major-league team. His work was shown at the Amp Studio in east Vancouver earlier this summer.)

The story of segregation in baseball is fraught with stories of athletes cruelly barred from play. Others tried to pass for white. In the demented hierarchy of Jim Crow baseball, Indigenous players were permitted, while any hint of African ancestry led to dismissal. Not surprisingly, several Black and mixed-race players tried to pass. The baseball historian Jay-Dell Mah of Nakusp, B.C., has researched the story of third baseman Dick Brookings, who was described in newspapers as being Cherokee. He played briefly for the professional Vancouver Beavers in 1909 before being run out of pro ball because of his race while playing for the Regina Bone Pilers in 1910.

Jimmy Claxton, born in the Vancouver Island coal mining community of Wellington, snuck across the colour barrier to pitch in two games for the professional Oakland Oaks before being released because of his African-American heritage.

The first Black player to suit up for a Vancouver professional team was California-born John Ritchey, a catcher who played for the Capilanos for two seasons beginning in 1951. Sports columnist Eric Whitehead of the Province gave credit for the signing to manager Bob Brown, whose “long career was steeped in the tradition that baseball was for whites only. It is a tribute to Ruby Robert that he has made a bow to the changing times and, in his 75th year, is going to give a coloured boy a break on his ball club.”

Vancouver had a thriving amateur baseball scene after the First World War with the champions of several rival leagues doing battle to claim city supremacy. Being outside of organized baseball meant amateur teams set their own rules on participation.

At least 25 players suited up for the Longshoremen in the 1920 season. Here are the stories of three of them.

Ab Mortimer

The best hitter in the City League in 1920 was Ebenezer Alexander Mortimer, known as Ab or Abe, a slugger who played first base and the outfield. At the Powell Street Grounds ceremony, Mortimer was presented a gold medal by Tisdalls, a sports goods store, a reward for the league’s best hitter. The Longshoreman had 18 hits, including two triples and two home runs, in 45 at-bats for a sizzling .400 average.

The six-foot-two, 210-pound Mortimer was a presence in amateur Vancouver baseball for decades. He played for several different teams in different leagues, while working as a teamster, longshoreman, sleeping-car porter and metal worker. He was born in New Westminster in 1889 to Lucretia Alexander and William Mortimer, a cook. His mother’s parents arrived in British Columbia from San Francisco in 1858. The Alexander family were prominent farmers in Central Saanich on Vancouver Island. Their ancestors include such prominent athletes as the lacrosse player Kevin Alexander, a member of the BC Sports Hall of Fame, and Doug Hudlin, an umpire who has been inducted into the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame.

Ab Mortimer was not the only athlete in his immediate family. An older brother, Oscar, fought successfully as a heavyweight boxer in the United States, where he suffered the indignity of being arrested in 1918 for violating Jim Crow laws by sitting in the white section of a Dallas streetcar.

After making the rounds of amateur baseball in Vancouver in the 1920s, he settled for a time in Alberta, playing for teams in Medicine Hat.

He signed up for duty in the Second World War after lying about his age (he was 51, but looked much younger), serving in Scotland with the Canadian Forestry Corps. While overseas, his family was informed he had been killed in a bombing raid after his identification was found in a ruin. He wrote home to say he was OK, but the letter never arrived. They only learned of his well-being when the corporal returned to Canada on leave. He had lost the papers later found in wreckage, leading to the confusion.

“So put it in the paper that I’m alive, will you?” he told a Vancouver Sun reporter. “That seems the only way I’ll ever get off the ghost list.”

His playing days over, Mortimer became an umpire. He became known for his entertaining call of balls and strikes. On a fourth ball, he was likely to cry: “Low. Take it and git,” dispatching the batter to first base.

He once told the sports reporter Archie McDonald that he had endured having had thrown at him a bottle, a cantaloupe, a watermelon, a blueberry pie and a bucket of cold water. He charged just $5 to work a game.

Late in life, he told reporters he had spent several seasons playing in the professional Negro leagues with the Kansas City Monarchs, though there is no evidence he was ever with the team. The claim likely reflects a desire to provide colourful material to reporters.

Mortimer was inducted into the Vancouver Baseball Hall of Fame at Capilano (now Nat Bailey) Stadium in 1967, two years before his death at Shaughnessy Hospital, which resulted from a stroke and a fall that cracked his hip.

Eddie Nahanee

Edward Gilbert Nahanee was born on the north shore of Burrard Inlet to a Squamish mother and a Kanaka father. He followed his father to work on the docks at age 14, loading logs and lumber for export. Nahanee was a star pitcher for the Longshoremen, though he was better known as a hurler for the Squamish Indian baseball team of the North Shore Baseball league.

He was a key player as the Indians won five consecutive league titles in the late 1920s under the guidance of the legendary Andy Paull. In 1929, they defeated championship teams from Point Grey, Vancouver and New Westminster before whitewashing the Victoria Capitals by 21-0 to claim the provincial senior B championship. A brother, Billy Nahanee, was also on the roster of the winning side.

After retiring from longshoreing in 1946, Nahanee became business agent for the Native Brotherhood of B.C. He spent three decades as an activist with the group, which advocated for First Nations workers and communities. “As a member of the Squamish Indian Band,” his family wrote in a 1989 obituary, “he spearheaded many battles to obtain justice on lands that were taken away (by) various governments.”

The family endured a terrible loss in 1945. Edward Nahanee Jr., a private first class with the U.S. Ninth Army in Northwestern Europe, was killed. The young man had tried to enlist in the Canadian forces soon after the outbreak of war only to be turned away when diagnosed with a heart condition. He moved in with his sister in Washington state and enlisted in the U.S. army.

The young man was the first among the Squamish Nation to be killed in the war. In 1949, more than four years after his death, his remains were returned to be buried at the Indian Mission Reserve Cemetery. A service was conducted at St. Paul’s Church after which a bugler played “The Last Post” and three volleys of rifle fire echoed across the inlet.

Jumbo Nahu

Herbert Nahu was repairing a road on the Western Front when his shovel struck a bomb, which exploded. Shrapnel tore into his neck near his larynx. Nahu’s war was over.

“Well nourished, muscular development good,” a medical officer wrote. “Medium height and heavily built.”

Nahu had difficulty swallowing, especially in cold or damp weather, and his voice was reduced to a whisper, but over time the effects of the injury lessened.

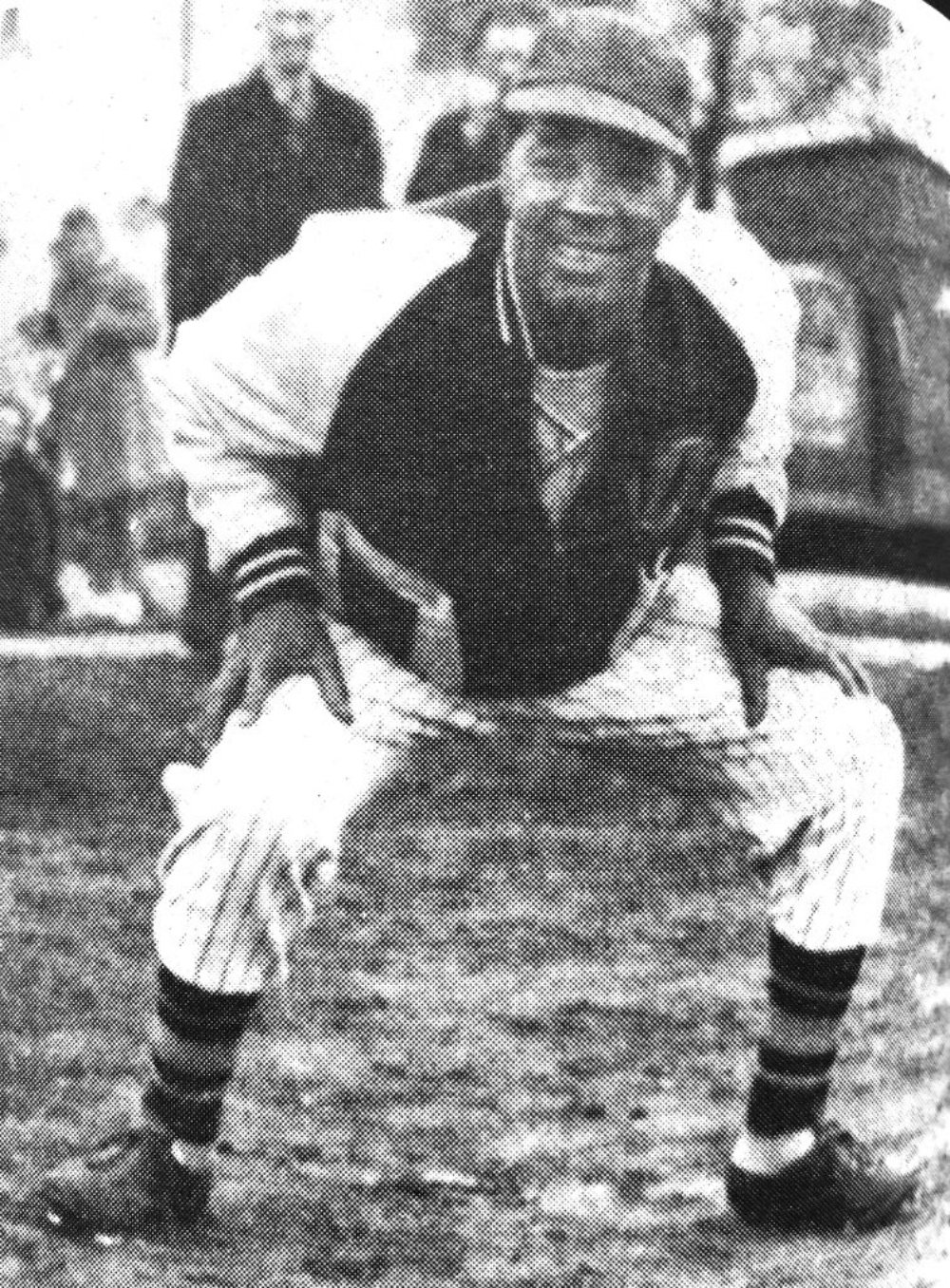

The five-foot-six, 190-pounder was a late addition to the Longshoremen’s baseball roster in 1920. He gave the lineup some needed clout. He also began piling on weight, playing shortstop and second base at a reported 247 pounds, thus gaining the nickname Jumbo.

On his death in 1957, at 65, he was described as one of the last survivors of Kanaka Row, a settlement in Moodyville (now North Vancouver) populated by people of Hawaiian ancestry. His family traced through roots to the House of Kamehameha, the Hawaiian royal family.

The family also endured a terrible tragedy. His little sister, Mary Clementine, was found murdered in a case that garnered banner headlines in the Vancouver newspapers. The Province offered a reward of $100 for information leading to a conviction, which they announced in a front-page box. The Vancouver World heralded the case with headlines taking up nearly the top half of page one. In the end, a vagrant was acquitted for lack of evidence and the case remained unsolved.

In later years, the murder was forgotten and the name Nahu became synonymous with sports excellence. Before going to war, Nahu had been a star swimmer.

On the first weekend in September, 1920, Nahu, Nahanee, Mortimer and the rest of the Longshoremen’s team faced a team featuring clerks employed by local haberdashers Archie Arnold and Charlie Quigley. The Arnold and Quigley team, nicknamed the Clothiers after the sponsors, had won the pennant for the rival commercial league.

It was a busy weekend for sports, as the Olympics were being held in Antwerp and the Mann Cup lacrosse showdown pitted Vancouver against New Westminster. In the end, Arnold and Quigley, known as A&Q, emerged victorious in a disputed series. They then went on to defeat Victoria for the provincial championship.

Incidentally, one of the A&Q players was a heavyset man named Tony Manson. Some newspaper stories described him as being Native. In fact, his birth name was Norman Frank Nahu. He was Jumbo’s older brother.

The I.L.A. team only lasted a few more seasons, as the union lost a violent strike in 1923 to be replaced by a company union. Their legacy is a baseball team which belied all the contemporary falsehoods about race. ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Labour + Industry

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: