On Richmond’s Alexandra Road, on the side of a building that houses an izakaya and a Korean fried chicken restaurant, I found a stretch of Himalayan blackberry, its canes crawling out from the cement like tentacles. Of course I had to try one. It was sour, and didn’t even taste like fried chicken.

But it revived idyllic summer memories as a child, hunting blackberries on family visits to Pender Island, folding the base of my T-shirt into a kangaroo pouch to carry my harvest. In Vancouver where I grew up, my family lived near the Langara Trail. Walking it in the heat of late August meant popping fruit into my mouth every few steps.

Lately I seem to see blackberries all over, which confirmed, I assumed, their ancient claim to this corner of the Pacific Northwest. There it was in parking lots, by the side of roads, under the SkyTrain, along the old Arbutus train corridor and behind New Westminster’s Starlight Casino, where a trail had been plugged by an aggressive thicket.

But when I looked online, I was surprised to learn the Himalayan blackberry is an invasive species. One that doesn’t even hail from the Himalayas. Rather, it’s from Armenia — where it gets its Latin name, Rubus armeniacus — and northern Iran.

So how did it get here?

As I traced the berry’s journey, I found myself flipping through the history of colonization, and into the stories of an American eugenicist, pooping gulls, ravenous deer and an ancient ice cream.

And beyond the moment when the Himalayan first touched down on West Coast soil, there lay an even older history of berries that have been enjoyed here by people and animals since glacial ice retreated from the land.

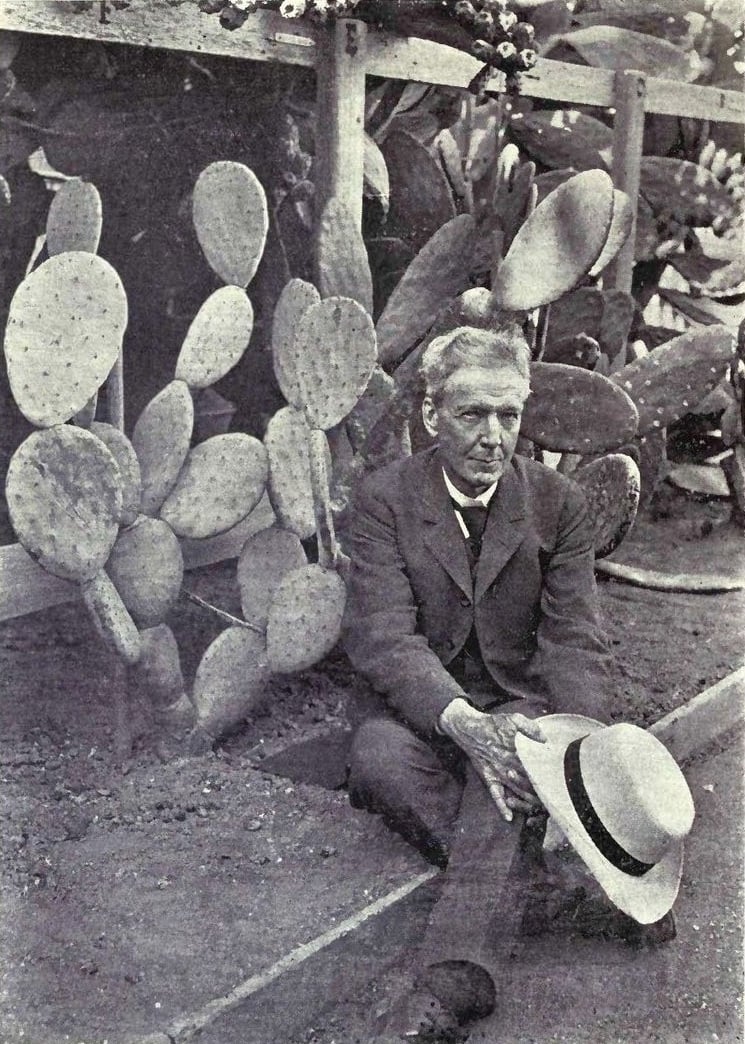

The arrival of the Himalayan blackberry in North America is widely assigned to an American horticulturalist named Luther Burbank. Born in 1849, he received little more than a high school education but was known for experimental plant breeding that tried to “take the rough spots out of nature.” He developed a spineless cactus, the stoneless Elberta peach, and the Russet Burbank potato, North America’s most widely grown species.

Burbank also believed that people should be bred to create “the finest race ever known,” and viewed the U.S. as the perfect garden for experimentation. He was a member of the Immigration Restriction League’s eugenics committee, which offered pseudoscientific criteria for which “better” races should be let in.

Burbank was based in Santa Rosa, Calif. and wanted to feed America’s growing middle-class fresh fruits and vegetables — nothing from a can. He created new varieties that would be tasty and tough enough to withstand rail shipment. His crops made him a household name and led to friendships with giants like Thomas Edison and Henry Ford. He was even painted posthumously by Frida Kahlo, who used his corpse as a reference.

Burbank was always eager to get his hands on new species and avidly traded seeds with collectors from around the world. As the story goes, one day in the mail he received the blackberry. He assumed the Rubus armeniacus came from India since that was where the package came from. So he called the blackberry the Himalaya Giant and introduced it around 1885. Burbank noticed that the plant did well in temperate climates. He targeted customers in the Pacific Northwest with a flyer in 1894.

The Armenian transplant, unlike other berries that appear annually, have stems with a two-year life cycle. In the first year, the prickled stems, called canes, emerge. They arch or trail along the ground up to 12 metres long and up to three metres high, even higher if there’s a tree or a Korean restaurant to rely on. In the second year the canes don’t grow any more, and instead produce side shoots from which flowers and fruits grow.

The Himalayan doesn’t like shade and can’t invade deep forests, but otherwise it’s a tenacious survivor. Seeds can last in the soil for several years. Root fragments that aren’t removed can sprout new plants. Underground runners at a metre deep can stretch over 10 metres and pop up from the soil with new shoots called suckers. If the tip of a first-year cane touches the ground, it roots, and an offspring plant is born.

Its cunning growth, threatening barbs and bold limbs remind me of fantastical fiction, like something from H.P. Lovecraft or the red weed from The War of the Worlds. It is charged with the crime of outcompeting other species of plants key to ecosystems. In the riparian zones of creeks and streams, for example, it crowds out native plants with deep roots, increasing erosion and flooding.

Here in August, “almost every bird and most people are eating blackberries,” said UBC forestry professor Peter Arcese. “I hate to say it, but you can imagine a rain of seed coming down from the birds.”

So the Himalayan really didn’t need Burbank’s mail orders to help it spread. With a fruit enticing to both humans and animals, the plant’s invasion of the West quickly took root.

“Europeans are great at bringing their own backyards wherever they go in the world, and that’s been a real problem,” said Nancy Turner, the noted ethnobotanist and professor emeritus at the University of Victoria’s School of Environmental Studies. Immigrants to Canada “thought they were doing a good deed by bringing these different plants and species and introducing agriculture in the European sense. It’s a natural thing. We like the food we’re raised on.”

Of course, the Europeans didn’t arrive to terra nullius, but stepped into the gardens of Indigenous peoples who had advanced systems of cultivating landscapes, from controlled burns to harvesting parts of plants while replanting others.

In the garden of Turner’s home on Protection Island are berries native to these lands you won’t find in a supermarket. She’s collaborated with Indigenous elders and cultural specialists for more than 40 years to document and retain their traditional knowledge of plants and habitats. Turner was gifted a nickname in the Tahltan language, Jjie Eghaden, which means “berry woman.”

The Himalayan might not be a B.C. native, but it has relatives from here that belong to the same rose family. Turner speaks of them intimately. The trailing blackberry, “tangyer and tastier than the Himalayan.” The red raspberry, “closely related to the one that grows wild in Europe.” The black cap raspberry, whose bushes are “very prickly” but are “very productive.” Thimbleberries, with big leaves like a maple tree, are, “bright red and juicy and fall off quite quickly when they’re ripe.” The salmonberry has “different colours depending on genetic variations, from gold to deep ruby red, almost black.”

In open woods, high elevations and peat bogs, you can find native berries in the genus Vaccinium, said Turner, such as blueberries, huckleberries and cranberries. Beyond that are more still: the salalberries of the heather family, and the currants and gooseberries of the Grossulariaceae family.

Aside from eating them as is, Indigenous people found myriad ways to prepare berries. One of them was drying them into cakes for winter, which if prepped and kept well, could be reconstituted in water overnight. “Everyone says it’s like having fresh berries again,” said Turner.

They also made fruit leather. Mary Thomas, a late Secwepemc Elder who was also an ethnobotanist, shared a memory with Turner.

“She talked about berry picking all the time, and how her granny would make this really special kind of fruit leather that was a mixture of black cap raspberry and blueberry, and she’d store it in a cotton sack. If the kids were really good, granny would bring out the bag and they knew they were in for a treat.”

One recipe intrigued settlers so much that they came up with their own name for it: Indian ice cream. It comes from the soapberry, an ancient plant that was one of the first to follow lichens and mosses after the ice sheets retreated from the West Coast.

“They fizz up just like soap!” said Denise Sparrow of the Musqueam Nation, who runs Salishan Catering. She has a soapberry liqueur in the works that requires 30 days to make, she said.

Soapberries contains saponin, a natural detergent, and produce a foam when squeezed. A number of different Indigenous peoples discovered that when the berry is whipped with water it turns into a stiff froth, like that of meringue.

Soapberries are sour, so they’re often used with other berries for colour and flavour. Saskatoon berries coloured the treat lavender, huckleberries added purple, and raspberries, a sweeter addition, made it red.

Artifacts like picking baskets for children, bark whisks and ornate wooden spoons tell of the special connection that people had with the berry and the culture that developed around it.

“All this shows the complexity of the knowledge that kept thousands of years of people well-fed and nourished,” said Turner.

With European contact, the passing of knowledge was violently interrupted.

“The impact of colonization was separation from the land. That was one of the main, fundamental pillars,” said ethnobotanist Leigh Joseph, whose ancestral name is Styawat. “There would be an Indian Agent on the reserve who people had to get a pass from to go and harvest. They’d be completely in the hands of that person.”

Then there were residential schools, which disrupted young Indigenous peoples’ connection with how the land nourished their ancestors physically, culturally, emotionally and spiritually. They would be denied access to “food that holds their identity and our way of understanding health, strength and wellness,” said Joseph.

Both of Joseph’s paternal grandparents attended residential school. Only in recent years has research begun to document how malnutrition in the schools has led to poor long-term health outcomes for Indigenous people.

For her generation, to be able to live from the land again is a “political act,” Joseph said. “Returning to harvesting and rebuilding my relationship with these plants is a really powerful and profound way to practice that healing.”

Joseph is Sḵwx̱wú7mesh, and one berry that has special meaning for her people is the salmonberry.

“Salmonberries mark the salmon run. It’s one of the first spring foods, and there was a joy associated with that time. The berries are the prized part, but there’s also the flowers and the shoots — my dad taught me that. He used to eat a lot of them.”

Called stsá7tskaý (pronounced saskay), Joseph’s father would pick the spring shoots while they were still easy to bend, like licorice. He’d peel them on the spot and eat them fresh as he played in the forest.

On Haida Gwaii off the northern Pacific coast, however, the arrival of what now seems a commonplace animal made a big change.

“In the old days, our ancestors made orchards out of wild trees so that they were in close proximity to the village for easy access, and the same with root plants and berry bushes,” said Kii’iljuus Barbara Wilson, an educator and plant expert of the Haida Nation. “A clan would always have berry patches on the side of a hill.”

Then, because settlers wanted something to hunt, they introduced the deer.

“Our world is very quiet because of the deer eating everything,” said Wilson, who is 77. “It’s very difficult to find berries now, and we suffer, but also the birds suffer. I’m a great-grandmother now. The thought that my great-granddaughter will never see the things I’ve experienced is quite sad.”

The Sitka black-tailed deer were brought over in at least six batches between 1878 and 1925. The mild winters and lack of predators allowed the deer to spread and increase so invasively that many plants used by the Haida for generations were decimated, such as the slow-growing devil’s club, which has many medicinal uses.

Climate change has also begun to affect berries. They’re threatened by the fluctuation in weather — “two years ago, we had such cold weather that a lot of the canes died,” said Wilson — and the decline of their pollinators. Over the past century, the bumblebee population has declined by almost half in North America.

“Berries have their own insect pollinators that they need to produce fruit,” explains Nancy Turner. “If there’s a mismatch, the berries won’t be as productive.”

Where humans go, the Himalayan follows.

Pooping animals play a role in spreading the berry’s seeds, said professor Arcese, but settlers are to blame for where they land and thrive.

Arcese used to work on Mandarte Island near Sidney Island, which was historically cultivated by the Tsawout and Tseycum peoples and once home to a number of plant species now extinct. After settlers arrived and created open garbage dumps nearby, the seagull population grew. More birds produced more feces and more nitrogen, which led to more blackberries. Arcese estimates that 20 per cent of the island is now covered in blackberry.

“It’s human disturbance that gives them the niche,” said Arcese. “It’s the human population growing and developing, flattening and building new landscapes. Those seeds wouldn’t germinate without habitat. Once they’re there, they dominate.”

Philip Pires, who’s owned Big Phil’s Rubbish Removal for 17 years, knows this better than most. Both the province and municipalities have called on him to clear blackberry from roads and property. In 2016, governments in Metro Vancouver spent almost $350,000 managing the plant.

“We’ve seen it all,” said Pires. “It doesn’t hold back.” This month, Pires was called by an Abbotsford homeowner to remove the blackberry engulfing the property and he found a trailer hidden in the plant’s clutches. “The owner didn’t even know it was there.”

To slay the plant, Pires’s Excalibur is a “secret” piece of expensive equipment that removes the plant in large chunks. He uses welding gloves to defend against the barbs, though they sometimes still pierce through.

In the work of decolonizing the landscape, it helps to know what does and doesn’t belong. In B.C., Green Teams educates young people on just that. The Vancouver and Victoria region teams go on outings to plant native trees like Garry oaks and bushes like salmonberries, while removing invasives like the Himalayan, which volunteers are often surprised to learn are troublemakers.

“They think everything’s green, so everything must be healthy,” said Lyda Salatian, who started the non-profit in 2011.

The volunteers might not have Big Phil’s expensive secret weapon, but they’ve learned how to dig out the Himalayan’s root crowns. They even compete to see who can unearth the biggest and weigh them at the end of a cleanup.

Earlier this year, volunteers at Colwood’s Perimeter Park removed blackberry that had engulfed a set of benches dedicated to loved ones. That’s how ruthlessly its prickly vines can advance.

“Invasive species,” said Joseph, “are a metaphor for imbalance and understanding the history of colonial impact and fast change.”

Still, Leigh Joseph tells me that no plant should be thought of as “inherently bad.” Rather, we should look at whether it’s a good fit in a particular environment. The Himalayan, for example, needs to be watched where it might overrun native species. But its foothold here is permanent. Life continues, like a twisting vine.

Growing up, Joseph told me, she visited her great aunt and uncle, who are Snuneymuxw, on their land along the Nanaimo River. To accompany the salmon that they caught and smoked on their property, her great aunt would make blackberry juice — “so, so delicious!” — from the Himalayan.

I think about the early settlers bringing in deer to shoot, and plants they wanted to eat. I think about the bees confused by what they’re finding, and the gulls gorging themselves on the dumps. I think about the people who lived here before the Europeans who learned from the land, and how we’re all learning to do so again.

This berry is a tasty teacher. ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: