Just off the corner of Renfrew and Grandview Highway in East Vancouver sits a dilapidated, two-storey restaurant with a rusting chain-link fence zigzagging around it. A faded yellow sign said the building was once the Ropongi Café, a restaurant with a billiards room on the top floor.

If you ask neighbours about the spot, they’ll tell you it’s been vacant for as long as they can remember. Guesses range from one to 20 years. They’ll tell you about squatters, graffiti and illegal dumping. But they’ll also whisper rumours of a fire, gang-style shootings and murder.

I grew up in the neighbourhood and the building has sat empty for as long as I can remember: boarded-up, crumbling and taking up much-valued real estate in a city deep in a housing crisis. I needed to know how a $3-million property, walking distance from a SkyTrain station, an elementary school, co-op housing and a community centre could sit empty in a city like Vancouver. Were rumours of murder true? Was the food any good?

I started knocking on doors, talking to neighbours, digging through newspaper archives and even filed a freedom of information request with the City of Vancouver to get the answers.

‘Will this property look like this forever???’

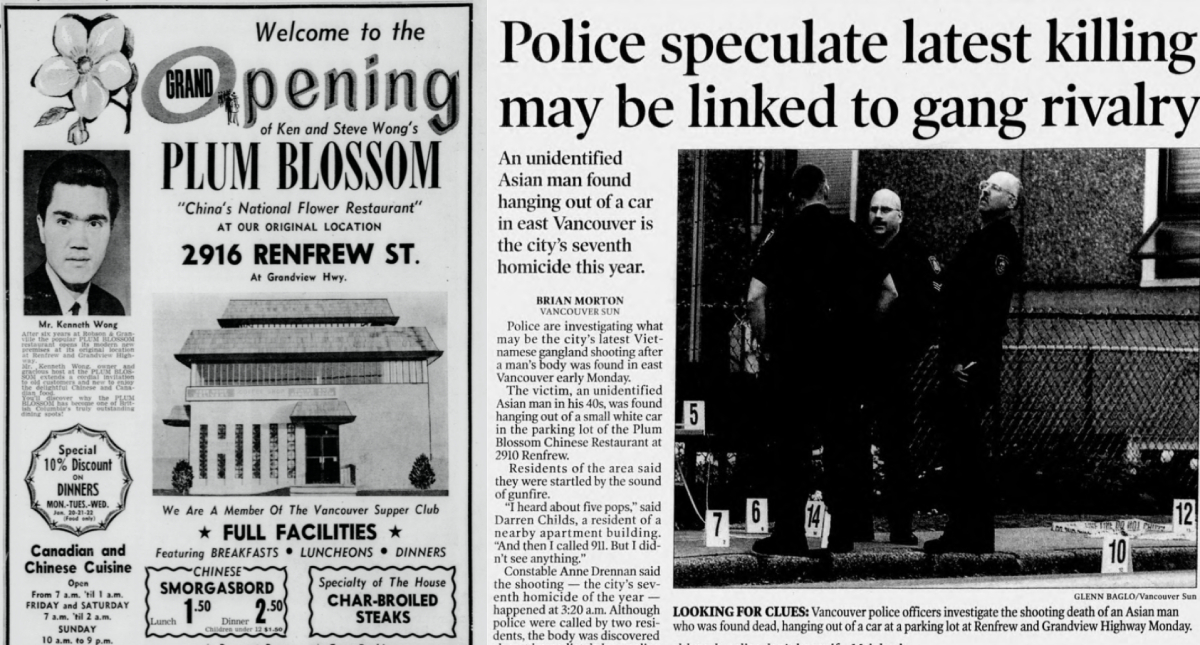

The building’s story starts on Jan. 17, 1969 with the grand opening of Ken and Steve Wong’s Plum Blossom Restaurant. An ad in the Province newspaper invited people to dine on a Chinese smorgasbord lunch for $1.50 or dinner for $2.50. The front-page story that day, “‘To Wake up the People,’ Czech Youths Vow to Die,” about the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia; Panasonic was advertising “the best black and white TV money could buy.”

Newspaper mentions of the restaurant in the ‘70s were mostly ads for Chinese food, or job postings for “experienced waitresses.” Then, the restaurant fades out of public records. Until the summer of 2000 with the headline, “Police speculate latest killing may be linked to gang rivalry.”

Turns out, the rumours were true. That May, a 40-year-old man was shot and killed in the parking lot of the Plum Blossom Restaurant.

The sound of gunfire woke Lori Egan up in the middle of the night. She remembers her husband Larry calling the police and a plain clothes officer telling them that they found a body. The victim was found hanging out of a small white car in the restaurant’s parking lot, which was Egan and her daughter’s shortcut to elementary school. Egan remembers having to cross the street to walk around the crime scene. “The body was still hanging out of the car,” Egan recalled. “The policeman walked with us kind of trying to block her [daughter from] seeing it.” Police alluded to gang-turf wars, but said the father of two was likely in the wrong place at the wrong time.

A title search shows that the restaurant changed owners in 1990 and again in 2004. The new owners started renovations and wanted to rename the restaurant Ropongi. Then in 2006, there was a fire in the building and Ropongi never opened. In 2007, new owners took over again.

The building has sat empty since that fire in 2006, over 14 years.

Neighbours complained. Squatters moved in and out. Other businesses nearby came and went.

In 2010, after years of ordering the owners to clean up the site and complaints from neighbours, the city declared it a nuisance building. The order describes the building as “so dilapidated or unclean as to be an offence to the community” adding it was “dangerous to public safety.” They ordered the owners to demolish the building — but nothing happened. So in 2011, the city told the owners if they didn’t demolish it, the city would. That was nine years ago.

The building “has sat unoccupied and in a state of mess and disrepair the entire time I have been living in this neighbourhood. The city advised me they were going to tear it down and the owner would have to pay for these charges. Nothing has happened,” wrote one complainant to the city in 2017. “Will this property look like this forever???”

So many empty lots, and many more complaints

Mitchell Reardon is drawn to unloved and overlooked spaces and has found ways to transform abandoned public spaces for events and gatherings. He’s a senior planner at the urban planning and design consultancy Happy City.

As part of Happy City’s Living Lab, Reardon teamed up with the University of Waterloo to look at how people’s well-being was impacted by the type of space they were in. They invited groups of people to take “psycho-physiological” walking tours’ through Vancouver’s West End. The team asked participants to take part in surveys, games, experiments and even measured their physical arousal with mobile bracelets. They found that people were less stressed in green spaces and happier in green and colourful spaces.

The lot at Renfrew and Grandview, according to Reardon, is likely having an impact on neighbours’ sense of safety, feelings of trust and sociability. While it’s way easier to transform unloved public spaces than private buildings, it’s not unheard of.

Granby Park, in Dublin, Ireland was a site that sat empty after developers pulled out and didn’t have the money to build. “In the end, a group of artists and neighbours worked with the developer to use the site temporarily,” wrote Reardon in an email, “and in doing so created what I still think was the best example of transforming an unloved space.”

The main tool the city has for compliance is the Standards of Maintenance Bylaw, the City of Vancouver told me in an email. “Through inspection and bylaw compliance by city inspectors, we can catch many issues early and work with the building owners and operators to address them.” Complaints from the public help them identify new or ongoing issues to hopefully, “avoid buildings being given a ‘nuisance’ status and can extend the life of many properties.”

The city says it takes a “proactive approach” to working with property owners and about six years ago, it created an interdepartmental work team that focuses on building inspections and bylaw compliance. Building inspectors, property use inspectors, legal services, fire inspectors, VPD officers and housing operations staff meet monthly to look at the most at-risk buildings in the city.

Since 2016, complaints about vacant buildings through the 311 number have increased 155 per cent from 84 to 214 in 2019. The city doesn’t keep track of the number of empty buildings or how long they’ve been empty.

Squatting in empty buildings might be the only option for people experiencing homelessness. Two-thousand two-hundred and twenty-three people were counted in the 2019 Vancouver Homeless Count; the highest it’s been since the count started in 2005. About 28 per cent of those counted were “unsheltered,” meaning they might be sleeping on the streets, or in alleys, doorways or parking lots.

“It was a bit scary,” when people would break into the building and come in and out, said Lori Egan. “But lately, it’s just an eyesore, I think what a shame, what a waste of space.” She and Larry have lived in an apartment behind the building for 38 years. They even ate at the Plum Blossom Restaurant.

The food was good, there was a big dining area, fish tanks and mirrors along the walls, Larry recalls. “Over the years it’s fallen into disrepair, and it’s unfortunate because it was nice for the neighbourhood to have that.”

Turns out, the current owner, James Ko, agrees with Larry and said he wants to open up a restaurant or other business again. At least, that was what he was planning to do when he bought it in 2007. I found Ko’s name and number on a “For Lease” sign going back through archived Google Earth images of the property.

When Ko bought the building, he said he completely redid the layout, gutted the inside and put the building up for lease. But no one was interested. Vandals would break in and steal things, break the windows or spray tags on the building. People would dump old furniture and mattresses on the site.

After the city declared the building a nuisance and threatened to tear it down, he says he started working more intensely on renovations. “Renovations cost a lot of money,” said Ko, who estimates he’s spent between $400,000 to $500,000.

A lot of work was put into redoing the inside of the building, he said, and so it might not seem like much from the outside. There was also red tape and, “a lot of bureaucracy to go through,” to get the permits he wanted to redo the building and put in an office upstairs.

“I am sorry to those people who have higher expectations of what they want to happen,” he said. So instead of a grand opening sign, there’s now a for sale sign on the lot. At this point, Ko’s skeptical if he can break even.

“I mean there comes down to a point whether you can afford to hold it, or you know, you have to let it go,” he said.

What’s next for the property is unknown. It could become another restaurant, office space or maybe with rezoning, housing. “Zoning forces you into certain kinds of boxes because it’s not like, do whatever you want here,” said Tsur Somerville, a UBC Sauder School of Business professor specializing in real estate finance.

Right now, the spot is zoned as C-1 Commercial, meaning specific businesses can be built there. With a land assembly, there could be rezoning for residential housing, Somerville speculates. But going through the rezoning process, “takes a lot of time, costs a lot of money and there’s no guarantee that it’s going to happen.”

While that might be frustrating to hear for most of the residents in the area, Mike Pepper has a different perspective. He’s lived in the small, blue, five-unit apartment building one house down from the empty building for eight years.

We stood in his grassy backyard by a picnic table under a giant cherry tree. Behind us was the lush greenery bordering Still Creek, masking the sounds and smells of busy Renfrew Street. Ducks lay eggs in the backyard and beavers come up from the creek at night, Pepper excitedly told me.

In front of us was the faded, pink brick wall of the former Plum Blossom Restaurant. Pepper heard about the murder in the parking lot and has seen squatters come in and out. But as a low-income renter, Pepper sees the building as protection from potential redevelopment of the entire block.

Pepper’s feelings speak to a fear that many people have of getting priced out or the thought that, “if that building goes down, mine might too,” said Reardon. Buildings like the empty Ropongi could actually be buffers that protect nearby spots from development.

“When that comes down, guess what’s happening to us?” Pepper said, pointing to the building; “We’re out.” So as long as it stays, “that’s the prettiest building in the world for me.”

What’s the mystery property in your community? We want to investigate it. Send details (and any photos) to [email protected] with the subject line “empty lot.” If we get enough suggestions, we’ll do a followup. ![]()

Read more: Local Economy, Housing

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: