The province is working to carve out new industrial zones for agricultural technology, saying the goal is better food security. But farmers, land-use experts and former NDP ministers are all raising concerns over the proposed location — on the arable soil of the Agricultural Land Reserve.

Last month, deputy minister of agriculture Wes Shoemaker was appointed head of a new effort to establish agri-industrial zones, “as recommended by” the BC NDP government’s Food Security Task Force, said an internal email obtained by The Tyee.

The recommendation, one of four in a new report titled “The Future of B.C.’s Food System,” is to convert up to 0.25 per cent of the Agricultural Land Reserve into agri-industrial zones.

Population growth and climate change may make agri-tech — which supports the production, processing and distribution of food — increasingly necessary. But proponents of the ALR warn about eliminating soil-based food production on 11,500 hectares of land. That’s the size of Vancouver.

The ALR was established in 1973 to protect B.C. farmland from overdevelopment. At a time when the province was losing as much as 6,000 hectares of land every year to urban sprawl, the NDP government under Dave Barrett placed the five per cent — or 4.7 million hectares — of the province that’s farmable into a reserve based on a soil-climate classification.

While the boundaries have shifted and the ALR is now home to swimming pools and pipelines in addition to blueberries and bison, it’s always been about food security, said former NDP environment minister Joan Sawicki, who was also one of the earliest employees of the Agricultural Land Commission charged with defending the reserve.

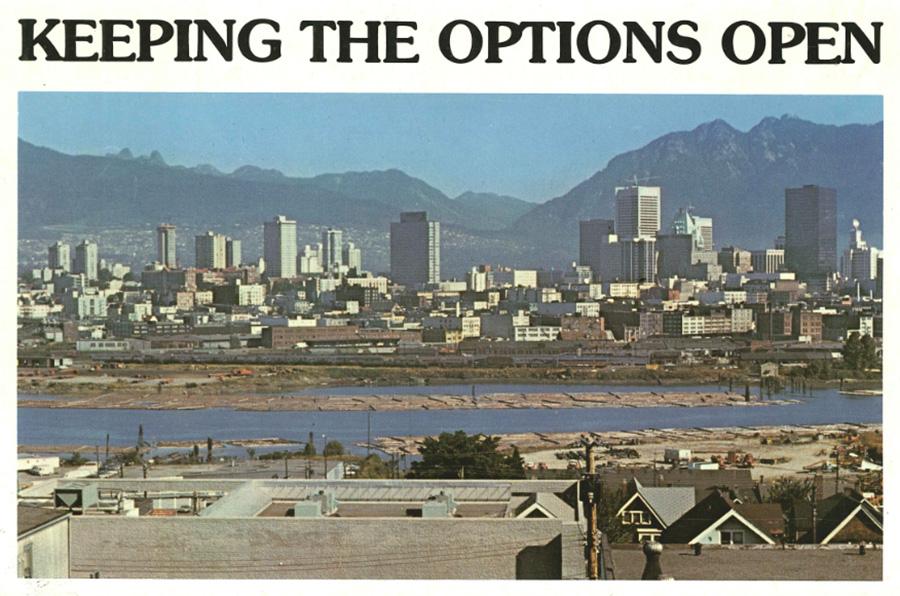

Sawicki said she remembers the first Land Commission brochure. Cover photos juxtaposed a farm in the foothills against industry along the Fraser River beneath the headline “Keeping the Options Open.” “That meant keeping the options open for food production, not only for now but for future generations,” Sawicki said.

Turning 11,500 hectares of soil into industrial warehousing closes that option, she said.

Sawicki co-signed an open letter, emailed on May 19 to premier John Horgan and Agriculture Minister Lana Popham, urging the government to redirect agri-tech outside the ALR. Signers, 23 in all, included land-use experts, soil scientists, farmers, academics and former ministers like herself.

Any plan to strengthen local food systems necessarily includes storage and processing facilities as well as farm innovation, as The Tyee has reported here and here. Still, at a time when COVID-19 is shining a light on the importance of local food production, some argue that it’s short-sighted to encroach on our limited store of farmland.

“It seems totally counterintuitive to start paving it over for an agri-tech industry that has to rely on a land base to create the food to support it,” Sawicki said.

An early act of the Agriculture Ministry of the BC NDP government was to repeal Bill 24 — which tried to divide the ALR into two zones based on soil class. The ministry has launched several initiatives to support local producers. The current government also commissioned a 2018 report focused on revitalizing the ALR and ALC, and bringing back an “agriculture first” approach to decision-making. “I'm having difficulty squaring the circle,” Sawicki said.

The government maintains that its core values are to protect farming and farmland. According to an emailed statement from Minister Popham, the mission of the new agri-tech secretariat is to help “build a safe, sustainable and resilient food system.” She added, “The secretariat will look at land-use opportunities in the province as a whole rather than at the ALR specifically.”

But keeping the ALR on the drawing board sets a bad precedent, said Sawicki.

Not only does it undermine the legislative mandate of the ALC and permanently cut up to 11,500 hectares from future food production, “it sends a message to land speculators everywhere that, once again, it is open season on B.C. farmland.”

Agri-tech and the future of food

The Food Security Task Force was formed in mid-2019 to provide recommendations for making B.C.’s agricultural sector more profitable, while protecting food production in the face of climate change.

The new report, released in January, suggests incorporating UN Sustainable Development Goals into agriculture; establishing an agri-tech “incubator-accelerator” as well as an agricultural research centre; and adopting a land-use strategy that creates agri-industrial zones inside the ALR.

Such zones could house indoor and vertical farms, processing facilities for added-value food products, and laboratories making cell-cultured proteins. Other spaces could study weather sensors, robots, pest management and food waste.

The challenges of population and climate change may require us to produce food in smaller spaces and with a lighter carbon footprint, the report says. Agri-tech could also mean big bucks: an estimated $25 million in revenue by 2025.

The federal government is banking on agri-tech, too. In 2017, Canada set a goal to reach $85 billion in agriculture, agri-food and seafood exports by 2025. That’s on top of $140 billion in domestic sales of homegrown and processed foods.

Proponents of the ALR don’t have a problem with agri-tech or industry per se; it just shouldn’t occur on land that we might need for future food production, said ALC chair Jennifer Dyson, who owns a water buffalo dairy farm on Vancouver Island.

A quarter of one per cent might not sound like much land, but when only five per cent of the province is farmable due to mountain topography, there has always been pressure. Nearly 50 years of urbanization since the ALR was formed — especially in Metro Vancouver, which happens to have the best farmland — has nibbled away at the reserve, despite the ALC mandate to protect it.

“We’re all vying for that same area,” Dyson said. “Those beautiful agricultural lands are also where most of the settlement exists.”

The task force cited a shortage of properly-zoned land and competition with other industries as two barriers for agri-tech outside the ALR. Dyson said inconsistent budgeting has hampered efforts to inventory land uses within the reserve, and that current baselines for existing farmland as well as industrial growth projections are both critical for decision-making.

“All the commission is saying is let’s do that due diligence,” Dyson said. “What are the bottlenecks for agri-tech or ag-industrial? What is agri-tech and ag-industrial? I think we need to define it.”

The dwindling ALR: ‘death by guppy bites’

Of course, this is not the first time ALR land has been targeted for development. There were the golf course wars of the late 1980s and the Six Mile Ranch battle a decade later. More recently, the Site C dam, “mega mansions,” breweries, cannabis and event spaces have all cropped up on fertile soil.

The ALR has always been controversial, but preserving farmland for food has also maintained strong public support over the lifetime of the reserve. It’s considered by some to be one of the most important pieces of provincial legislation to date, credited with preserving the character, health and livability of communities and acting as a boundary for urban growth.

“It’s begrudging to some and applauded by others,” Dyson said. “You couldn’t do it today. It truly was visionary.”

When the Land Commission Act passed in 1973, it superseded most other legislation. But over the years, agencies stopped engaging with the ALC, diluting the commission’s power to do its job of protecting food security.

The pressures that inspired the act in the first place are the same pressures that will always exist: the desire to snap up cheap farmland for growing communities or more lucrative purposes.

“We always say at the commission that it’s death by guppy bites,” Dyson said. “It’s this insatiable need for more land.”

But the more that farmland is developed, the less viable agriculture becomes. Adding a residence can double the value of land, which in Metro Vancouver already runs $150,000 to $350,000 per acre for a small plot.

“Unless I’m farming diamonds, it’s pretty hard to get that return on investment,” said Dyson.

The long view to food security

For retired orchardist and former ALC chair Richard Bullock, the biggest frustration about the new agri-industrial recommendation is having to rehash old arguments that he thought were settled.

After his tumultuous tenure with the ALC from 2010 to 2015 — which saw medical marijuana and the Site C dam approved on farmland as well as oil wells in need of clean up — he believed things were improving.

“I’m very disappointed that we’re having to deal with this,” Bullock said. “At this point in time, I thought that argument [about land availability] was over.

He said it all comes down to money, and the convenience of building on the valley floor versus up on the rocky hillsides where food can’t easily grow.

“I see all kinds of room that they could build on,” Bullock said, speaking from the porch of his Kelowna farmhouse. “But they’re going to have to run the sewers about six miles.”

His comments echo a speech that then-premier Mike Harcourt gave about the ALR in 1993. “We can’t keep putting pressure on our agricultural lands,” Harcourt said. “We’ve got to find ways of moving urban growth up not out... up in urban densities and up on to hillsides, not out into rich valley farmlands.”

Bullock said he’s not only looking out and up from his home orchard. He’s looking generations beyond his own lifetime — to a warmer era when B.C. farmland will likely be even more valuable.

The ALR has always been about securing food production beyond four-year government terms and short-term profits.

“I can push a building over and put a new one up, but I can’t pave over farmland and make any use of it after that. It’s gone,” Bullock said. “The most basic commodity that the world needs is food, to feed its people and its creatures. That land should be sacrosanct.” ![]()

Read more: Food, Environment, Urban Planning + Architecture

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: