Svend Robinson swears he didn’t plan this ahead of time. He’s showing me a letter he just received from a 75-year-old woman in Black Diamond, Alberta, urging him to do whatever he can to ensure that the federal NDP addresses climate change as the emergency it is. Enclosed with the letter is a handwritten cheque for $20.

“That for me is exciting,” says Robinson, who turned 67 this spring, “that there are people out there who feel that sense of urgency, and we are the political movement that’s got to respond to that.”

Robinson and I are sitting in a vacant storefront in north Burnaby. He gestures like a theatre director on an empty stage.

To our east, up on Burnaby Mountain, is the tank farm where the Trans Mountain pipeline just received the federal Liberal government’s approval to pump 890,000 barrels of bitumen each day from the oil sands.

To our north, down in Burrard Inlet, is where more than 30 oil tankers a month will carry their climate-destroying cargo out to the Pacific Ocean, assuming the project can surmount legal challenges from the Tsleil-Waututh and Squamish First Nations.*

This cavernous room, a former bicycle shop on Hastings Street painted teal green and filled with empty desks and stacks of chairs, will over the following months transform into the campaign headquarters for Robinson’s return to politics. When it comes to climate change, he says, the upcoming federal election in October “is our last chance to turn things around.”

Like many things Robinson says, there are several layers to this statement.

The personal — after 25 years as one of the country’s most progressive, effective and media-savvy NDP MPs, including becoming the first openly gay federal politician to win an election in Canadian history, Robinson resigned in 2004 after stealing — and then returning — a $21,500 diamond ring from an auction, an event he attributed to unaddressed mental health issues. This is his first attempt at a political comeback since 2006, and if he doesn’t succeed, it could be his last.

Then there is the political — Robinson believes the NDP’s steep fall from 95 to 44 seats in the 2015 federal election was due to the party abandoning its grassroots values in favour of “mushy” centrism, promising balanced budgets instead of justice for Canada’s most vulnerable and the environment that sustains us. With the rise of politicians like Bernie Sanders and Jeremy Corbyn — with whom he personally associated during his career — Robinson thinks it’s time for an insurgent political left to remake the NDP.

Robinson says his return to politics is driven by “a deep concern about the direction of my party, particularly after the last federal election. The direction that the party took then was, I think, disastrous. We paid the price for it.”

And also the planetary — Robinson, like many Canadians, was terrified by the United Nations report calculating humankind has only 11 years to halve global emissions before we’re locked into warming that may permanently flood the city of Richmond and lead to wildfire seasons many times worse than what we already experience. He thinks it should be the number one priority of Canada’s federal government to “rapidly transition away from fossil fuels.”

With his campaign barely even under way, Robinson has already called out Jagmeet Singh for supporting the fracking of natural gas, arguably helping to shift the NDP leader — as well as the party itself — towards a more aggressive position on fixing our climate crisis.

But in the 15 years he’s been absent from federal politics, a new generation of activists and politicians — ranging from Black Lives Matter and Idle No More to the unapologetic millennial socialism of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and truth-telling bluntness of Greta Thunberg — has redefined the tools, tactics and outlook of our political era.

“I have a lot of respect for the work he’s done over the years,” says Amita Kuttner, a 28-year-old Green Party candidate and astrophysicist running against Robinson this election in Burnaby North-Seymour, “and I also think it’s time for something new.”

Early master of media moments

It’s hard not to see similarities between Robinson’s political rise in the late 1970s and today’s ascension of Ocasio-Cortez in Washington, D.C. Like the 29-year-old congresswoman from the Bronx and Queens, a 25-year-old Robinson won the NDP nomination for Burnaby in 1977 by besting an older establishment candidate — in this case the 54-year-old president of Simon Fraser University, Dr. Pauline Jewett. He went on to win a seat in Parliament in the 1979 election. Robinson was a photogenic and articulate MP. He used his frequent media appearances to advance policies well to the left of the NDP leadership.

One of Robinson’s first moments of national attention came in July 1979. The RCMP was trying to locate and deport a 22-year-old Chilean student leader named Galindo Madrid. Convinced this would be a death sentence for Madrid, who’d fled Chile after criticizing the dictator Augusto Pinochet, Robinson defied RCMP orders by inviting Madrid to stay at his Burnaby home. It became a major news story that eventually led to Madrid becoming a Canadian citizen.

In saving Madrid from deportation and possible torture and execution, Robinson had discovered a way to force change without actually being in the governing political party: identify an injustice, create a dramatic moment around it that the media can’t ignore and build public pressure for a solution.

“Once you’ve studied his career, you see that there’s a bit of a formula for the way he works, and that was kind of the first example of that,” says Graeme Truelove, author of the 2013 book Svend Robinson: A Life in Politics. “I think he took that example and he was like, ‘If I could do that once, let’s see if I can do it again.’”

Over the next 25 years, Robinson joined Haida elders on a logging blockade in Haida Gwaii, advocated for the right to physician-assisted suicide of a woman named Sue Rodriguez, played a crucial behind-the-scenes role in creating the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, served 14 days in jail for taking part in a logging protest at Clayoquot Sound, heckled Ronald Reagan during the U.S. president’s speech to the House of Commons and was the only foreign politician to visit Kosovo during the early days of the NATO bombing campaign.

“It’s hard to reduce his achievements down to one or two things, but if it was going to be one I think it would be hard to argue anything other than his impact by coming out and being elected as the first openly gay MP,” Truelove says, a milestone that Robinson achieved in 1988. “That changed the rules of what’s possible.”

It helped excite the imagination of people like Paul Taylor, a young anti-poverty activist and Green New Deal advocate who recently won the NDP nomination in Parkdale-High Park in Toronto. “In addition to being a 37-year-old black dude, I’m also queer,” he says. “My mother told me about [Robinson] a long, long time ago. I was really young but I just thought it was the coolest thing.”

The charismatic radical

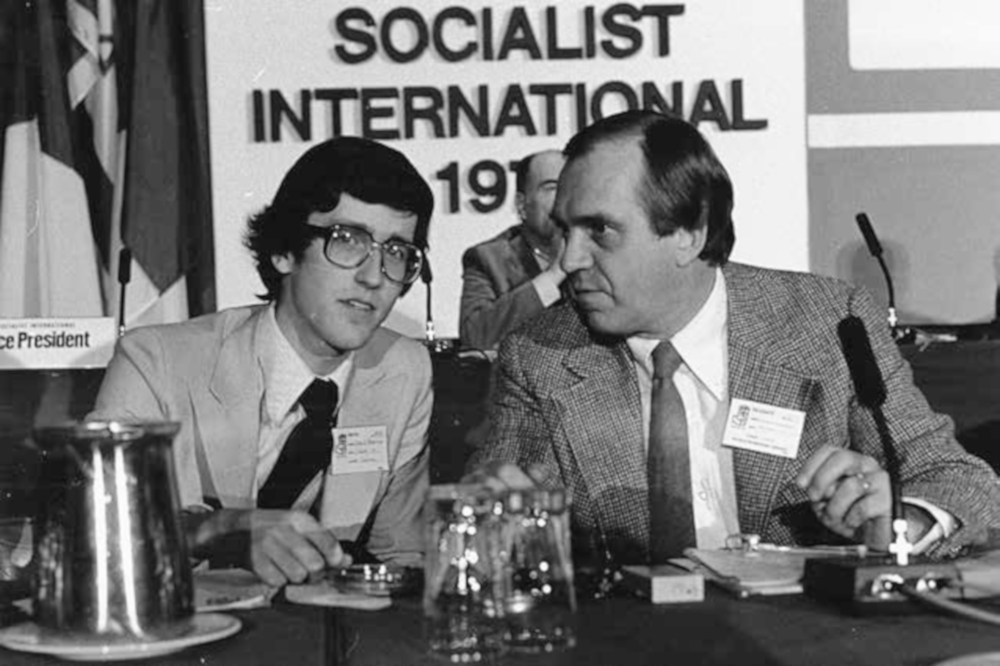

Robinson was about as left-wing a politician as they come. He listened to Bernie Sanders give speeches at Democratic Socialists of America gatherings, had several conversations with Jeremy Corbyn in London and met with Fidel Castro in Havana. The Cuban president jokingly referred to Robinson as “the last surviving socialist MP in Canada.” But the key to Robinson’s political longevity was how hard he worked for his constituents in Burnaby.

Derrick O’Keefe was in Grade 12 when he first met Robinson. He was working on an assignment for a high school journalism course and reached out to Robinson for an interview. To his surprise, the famous NDP MP met with him for almost an hour. “It gives you a little picture of what a workaholic he was and how responsive he was to everybody who contacted him,” says O’Keefe, who went on to co-found the media outlet Ricochet and run unsuccessfully for Vancouver city council with COPE in 2018. “He was probably unique in the history of Canadian politics in that he combines a very radical, explicitly socialist ideology with unrivalled politician skills.”

Robinson’s deep connection to the people he represented served multiple purposes. It provided him cover to advance causes and policies outside the realm of accepted debate. Robinson’s theory of change also rests on the idea that politicians should use their privileged position to amplify the voices of people typically ignored by the political, business and media establishment.

In 2001, Robinson and his good friend Libby Davies, at the time a second-term NDP MP from Vancouver-East, put their support behind something called the New Politics Initiative, an effort to disband the NDP and create a new party that would attempt to unite labour groups, anti-poverty activists, Indigenous leaders, environmental organizations and other progressive voices with actual office-seeking politicians. The initiative was voted down at an NDP convention in November 2001 but received 40 per cent support, a signal to Davies that a large faction of NDP members wanted “to see the party work in a different kind of way.”

Less than three years later, Robinson’s political career was over. On April 8, 2004, two weeks after he appeared on stage at Vancouver’s Orpheum Theatre with Noam Chomsky to celebrate his 25th year as an MP, Robinson walked into an auction near the airport, put a $21,500 diamond ring in his pocket, looked into a security camera, got into his car, returned to the auction to grab his phone, which he’d forgotten on a chair, and then drove home. “I realized immediately, ‘My God, what is this madness?’” he later told Truelove.

One of the people Robinson immediately reached out to was Davies. “He told me what had happened and came and saw me in my office. I remember it very well,” she says. Robinson contacted the auction house, spoke with RCMP and called a press conference, which Davies appeared at standing directly to his side. “I felt it was very important to support him,” she says. “What happened was shocking.”

Robinson explained to reporters he’d been under intense emotional stress. “Something just snapped in this moment of total, utter irrationality,” he said.

Robinson resigned his seat and ended up serving 100 hours of community service, along with a year of probation. He was later diagnosed with a form of bipolar disorder. In his biography of Robinson, Truelove explored other potential factors: a childhood spent with an alcoholic and abusive father, a near-fatal hiking accident on Gabriola Island in 1997 that possibly left Robinson with untreated PTSD, a punishing and unrelenting work schedule that left little time for self-care or reflection. “It was something that baffled me,” Truelove says. “I learned a lot about the complex things that went into that.”

‘Nobody’s even raised it’

This isn’t Robinson’s first attempt at a political comeback. In 2006, against the advice of then NDP leader Jack Layton, Robinson competed for a seat in Vancouver-Centre. Province columnist Don Martin wrote at the time that “the reinvented New Democrats have a very familiar ring,” and referred to Robinson as a “bipolarizing retread.”

Robinson lost to Liberal candidate Hedy Fry by over 8,000 votes. Now, after more than a decade working in Switzerland for the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, he says the theft is no longer something that should define him.

“I haven’t had any negative feedback on that all,” he explains. “I’ve knocked on hundreds of doors, nobody’s even asked about. It was 15 years ago, I’ve been doing humanitarian work since then, I was dealing with some pretty tough mental health issues at the time. Nobody’s even raised it; it’s not an issue.”

Robinson says voters are far more preoccupied with the existential threat posed by rising global temperatures and how political leaders plan to avert it. With the United Nations calling for a 45 per cent reduction in global emissions by 2030, “we’ve got to leave a lot of that oil and gas in the ground,” he says.

When Green candidate Paul Manly trounced the NDP in this spring’s Nanaimo-Ladysmith byelection, Robinson deemed it “a wake-up call” on Twitter. It was then that he zeroed in on Singh’s support of fracked LNG, saying, “He’s got to step up,” and, “We’ve got to be a lot bolder.”

Facing similar criticism from activists across the country, Singh in May said that “the future of Canada does not include fracking.” Later that month the NDP released a climate platform promising to spend $15 billion creating 300,000 jobs in the shift away from fossil fuels.

Svend Robinson wants to see even more money spent. “Is $15 billion enough? No.” And he acknowledges the platform itself makes no mention of winding down natural gas. “It’s not in the actual document,” he says, but at least now Singh is “on the record saying we oppose fracking.”

Assurances like that aren’t good enough for Kuttner, the Green candidate running against Robinson in Burnaby North-Seymour. “I feel like they’re kind of wavering on the fracking issue, which is problematic.” The Green Party climate plan promises to “Ban fracking. No exceptions.”

And where the NDP vows to develop greenhouse gas reduction targets in line with what is required to stabilize global temperature rise at 1.5 degrees Celsius, the Greens articulate such targets explicitly — a 60 per cent reduction in Canada’s emissions from 2005 levels by 2030.

But some NDP insiders warn Robinson’s climate-driven prescription for the party will only weaken its chances at the polls. “For the federal New Democratic Party to refute the policy decisions of the John Horgan government now in British Columbia, and to previously refute those of Rachel Notley’s NDP government in Alberta, it shows a party that does not understand power or politics,” says Bill Tieleman, the former BC NDP strategist and former regular columnist for The Tyee who provides lobbying and advice to labour unions and other groups.

“Oil and gas extraction, sale and exports are a huge part of our economy and the revenue governments derive from them, as well as the taxes of workers in those industries, is critical to funding our healthcare, education, public and social services,” notes Tieleman.

“Unionized construction and natural resource workers are increasingly left with few reasons to vote NDP — and yet they once were and still should be at the heart of the party.” Voters will be left to choose between a “pale green NDP” vying with a “real Green party.”

If the approach of Svend Robinson prevails,” Tieleman concludes, “that doesn’t leave many votes for an NDP which appears less like a Social Democratic party and more like a radical environmental group.”

‘Twitter with a vengeance’

Robinson has always been one or two steps ahead of the political mainstream. In some areas he’s now trying to catch up. The politician who once had no trouble attracting newspaper and TV attention is adjusting to a completely different era. “I have been a total Luddite. Until four months ago I was nowhere on social media,” he says. “I’ve now taken to Twitter with a vengeance. It does really give you the opportunity to respond contemporaneously as issues arise that didn’t exist previously.”

The political left is now linking questions of economic, racial and environmental justice that a generation ago many people considered separate. Politicians like Taylor — who is millennial, black, queer and socialist — is among those trying to import the intersectional vision of Ocasio-Cortez’s Green New Deal to Canada.

Recently endorsed by Naomi Klein, Taylor argues the housing crisis, climate change, soaring inequality and the ongoing impacts of colonialization on Indigenous peoples are deeply connected. “It’s a real opportunity to come up with that new deal that addresses all those things,” he says.

In a sense this is a continuation of the New Politics Initiative framework that Robinson and Davies were pushing nearly two decades ago. Yet it’s being most strongly enunciated by a millennial generation that came of age politically while Robinson was away in Europe. “I’m sure there are areas where he has blind spots or ways of doing things that are from an era prior to social media, prior to all the different social movements of the past 15 years,” O’Keefe says. “But the one thing about Svend is that he’s an incredible intellect and hard worker.”

Davies thinks the learning could go both ways. She sees candidates like Taylor bringing insurgent progressive energy to an NDP that’s been drifting towards the political centre. “I feel it’s important for people like me who’ve been around a while, you know, I’m the older generation now, to support these folks,” she says. If Robinson is elected in October, she adds, “he would be a great mentor.”

For now, however, it’s just Robinson and me sitting in an empty room in Burnaby. As our conversation comes to an end, I ask him to describe what this vacant storefront will look like closer to election day. “Hopefully it’ll be full of people, full of volunteers, full of grassroots activists on the phones, phoning people, getting the message out,” he says.

Robinson can see it all clearly. He speaks with the cautious bravado of a theatre director whose latest performance has yet to be cast and staged.

*Story corrected June 24 at 11 a.m. ![]()

Read more: Election 2019, Federal Politics, Elections, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: