A large warehouse sits next to the banks of the Fraser River in Delta, and it’s as grey and ordinary as the others surrounding it. Behind its front door is a melee of bright lights, piles of boxes, a small crew and a model. All is ready for today’s photoshoot.

After some last moments of preparation, the model walks onto the set and disrobes to reveal two double-D breasts. She stands confidently in front of the camera. Those breasts, however, are not hers. In fact, they’re detachable.

The model is wearing breast forms: prostheses that imitate real breasts. They’re often used by women who’ve had their breasts surgically removed due to breast cancer. Here, at The Breast Form Store, these prostheses are sold and shipped to customers all over the world. But the company caters to a different kind of customer.

The store’s mission today is to serve the global trans and cross-dressing communities. The store’s operations are spearheaded by the Perry family, for whom topless, breast form photoshoots are just another day at the office.

No family secrets

The year is 1993. The classic television comedy Cheers has ended its 11-year run. Basketball legend Michael Jordan is about to retire. Whitney Houston’s “I Will Always Love You” is at the top of the charts. And the World Wide Web is still new.

Victor and Eleanor Perry are seated at the dinner table in their townhouse in Steveston, B.C. Their two children, Tamar and Oren, are listening to the conversation. They’re old enough to hear this. Tamar is 22, and Oren is 15. There are no secrets in this family.

Eleanor has been working at Chrysalis Vancouver, a mastectomy store at the corner of Hastings and Granville Streets, for three years. At Chrysalis, the owners told Eleanor that men might call and ask to be fitted for breast forms. It was up to her to decide if she wanted to help them.

Victor had reservations at first. Eleanor would be working long hours by herself, and Victor was fearful for her safety. He called the police to ask for guidance, but after expressing his concerns to the officer, he heard a small chuckle. After a slight pause, the officer answered calmly.

“Think about it, sir. These people are not going to be interested in attacking your wife.”

At the time, Victor was satisfied with his response. If the police officer wasn’t worried, why should he be?

Looking back, he recognizes the danger of such perceptions. The officer’s response perpetuated some of the biggest and most enduring myths about gender. Trans people can be attracted to any gender. More importantly, they’re not dangerous.

Victor and Eleanor tell me that back then they felt new and naïve as they entered this world. To be fair, it was the early 1990s — the dawn before the Internet boom. No one was talking much about the changeability of gender much, and information was less accessible. They soon realized that the learning curve would be steep.

So, after brief consideration, Eleanor chose to help whomever entered the store regardless of gender. After some time, and with encouragement and emotional support from Victor, she decided to break out onto her own.

There was a space in the Fairmont Medical Building on West Broadway that was up for grabs. Eleanor planned to continue serving mastectomy customers during the day. After hours, she would continue to serve people from the transgender and cross-dressing communities.

Her store was a success, and she became a well-known figure among trans and cross-dressing people, with a reputation for being open-minded, caring and generous — so much so that she was invited to attend one of her customers’ support groups to show her products.

Victor accompanied her but didn’t go inside.

“I was shy,” Victor said. “I also didn’t want to make them uncomfortable. So, I sat in the car.” But one night, as he sat there alternating between a book and the weekly crossword puzzle, he was asked to join. “The more we learned about these people, the more we learned that they were just ordinary people.”

A few months later, Victor hopped online. What did the World Wide Web have to offer the transgender and cross-dressing community? Very little, he discovered.

The majority of breast form companies were unapproachable and untrustworthy. Friendly customer services representatives were a myth for trans people. Whether or not a consumer had actually received their product was no concern of theirs.

“Very few men in the early 1990s would have been brave enough to phone their credit card company to complain they did not receive their breast forms,” Victor said. “Eleanor and I saw an opportunity to revolutionize the way transgender and cross-dressing persons were helped on the Internet.”

In 1994, it was time for another dinner announcement at the Perry family table.

Victor was going to open an e-commerce store. It would ship primarily to those in the trans and cross-dressing communities all around the world. His office would be in the bedroom. He would post a 1-800 number for everyone to find. It would be separate from Eleanor’s store and run entirely by Victor. And just like that, The Breast Form Store was born.

‘That was my first time going to a bar in drag, and I was hooked’

Mercedes always wanted to be an entertainer. When she was 10, she would watch TV and admire the glamour of all the women on screen. Then along came Cher, and Mercedes knew from that moment on what she wanted to do for the rest of her life. Although she would do it a bit differently.

Until then Mercedes, who asked for anonymity in this story for privacy reasons, had always dressed as and been considered a boy. At 16, she dressed up as a woman for the first time, curled her hair and did her makeup. Then she slipped into a borrowed dress and a pair of tall high heels and walked into a bar.

“That was my first time going to a bar in drag,” says Mercedes, “and I was hooked.”

Drag queens are not the same as trans women. For trans women, the transition to a woman is a matter of identity. Performing drag, on the other hand, is a matter of performance.

Mercedes works in Calgary. Each night, she steps onstage and tries to give the audience a show they will always remember, and she does it all in a backless, or even strapless, dress and breast forms. “I want to look as real-girl as possible,” she says.

What did she and other drag queens use before breast forms became accessible?

“There were nerf balls,” she says with a laugh. “We stuffed pantyhose with rice. We did all kinds of things to create all kinds of illusions.”

She notes that many queens would also contact mastectomy stores. “If you found an operator that was open, then great, but other than that you didn’t get a warm reception.” The Breast Form Store changed that, she says.

It took some time. It seemed like every night as the Perry family sat down for dinner, someone would call the 1-800 number. A ring would echo from the bedroom into the dining room. Victor would push his chair back, stand and walk briskly to the phone. Then the ringing would stop.

It would happen again and again and again. On other occasions, Victor would answer the phone, and the caller would hang up with an abrupt click.

It took some time for customers to get used to Victor but by 1996, Victor quit his job to work on the store full time.

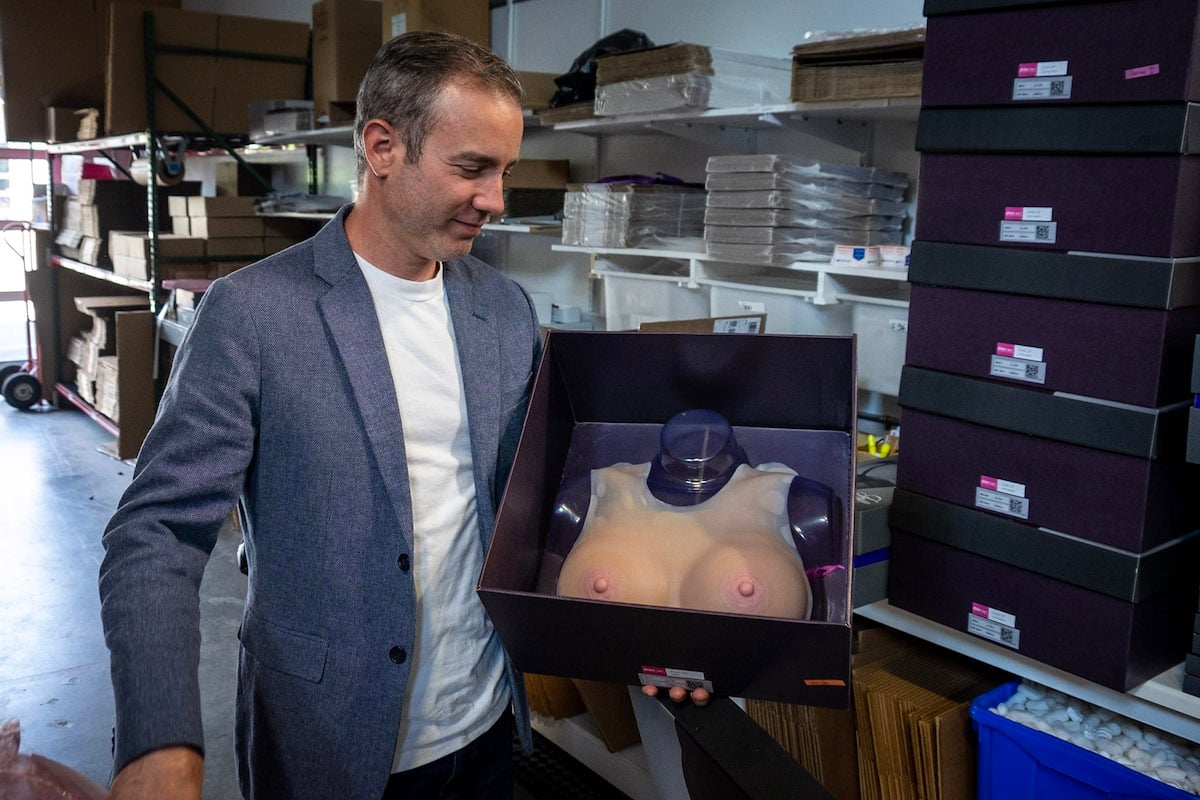

Twenty-five years later from its web launch, the phones in the warehouse don’t stop ringing. The reputation of The Breast Form Store has grown, and so has the business. In fact, it’s now a manufacturer, but this time led by a new generation.

The new normal

Tamar Perry has had a long day, but it’s not finished yet. She’s now married, a mother of two, and the warehouse manager at The Breast Form Store. Most nights she has something that she needs to get done and never hesitates to enlist her two young boys to help her.

“I would bring nipples home in packages with their adhesives. And we would sit there around the coffee table packing nipples into baggies,” Tamar said with a laugh. “It’s something we would do in front of the TV.”

It’s like holding up a mirror to that night in 1993, only one generation later. This is their normal. No secrets.

“In elementary school,” Tamar said, “I had to inform their teachers that if the boys come to school and start talking about boobies or breast forms or nipples, it’s because this is the nature of our business. And they’re not trying to be offensive in any way. It’s just that this is the fact of life around our house.”

Tamar’s brother, Oren Perry, is now the store’s CEO. Oren was born in Israel and grew up in a kibbutz there until the Perry family returned to Canada in 1990. “It was kind of like a commune based on socialist ideologies, so I really wasn’t exposed to the outside world,” Oren said. “I didn’t realize that trans people existed.”

When he finally learned about the trans and cross-dressing communities as a teenager, he wasn’t sure if his father would ever see a profit. He thought the customer base was just too small.

If you’re wondering how Oren’s childhood differed from that of other kids his age, it didn’t. Except for a few snide remarks from high school friends who knew about the family business, Oren remembers it as normal. And when his father wanted to retire in 2011 at the age of 67, Oren and his brother-in-law decided to buy the store.

Since then, they’ve expanded the business. Before it was just breast forms. Now they manufacture everything from thigh shapers to smoothing gaffs. The shapers give the thighs a slim, smooth look while the gaffs, as the store’s website says, “help keep ‘the boys’ tucked away and help create a flatter, smoother front.”

They also sell jewellery, wigs, makeup and lingerie. They have seven versions of their website for seven different world regions: Canada, the United States, Japan, Germany, France, the United Kingdom and Australia.

In 2013, the store was featured on season five of RuPaul’s Drag Race, and in her 2017 memoir, Caitlyn Jenner revealed that she was a frequent customer of The Breast Form Store before her coming out.

Within the trans and cross-dressing communities, The Breast Form Store is well known. But when the store first started, Victor and Eleanor just told people that they were taking Eleanor’s store online. Victor’s mom was one of the very few people who knew the whole truth.

Most everyone knows about the business now: friends, extended family, even the occasional acquaintance. But Tamar and Oren don’t always expect other people to be open to the work they do.

If either of them is meeting someone for the first time, they feel out if they’re receptive or not. If they are, they tell the truth about the family business. If not, then a partial truth is delivered.

“We say we just sell mastectomy products, which is not not telling the truth,” said Tamar. “It’s just not going into detail who we’re selling the mastectomy products to.”

Tamar likes to say that the world is a melting pot, but sometimes we live in one of the pot’s many bubbles. Her bubble is filled with diversity. Her company has customers everywhere, including Japan, the Middle East and the American Bible Belt.

But there’s one thing that the majority of the store’s customers have in common. They’re usually middle-aged or older — a product of a very judgmental world.

Beth’s first fitting

It was Dec. 22, 1988. Beth — who we've also made anonymous — was driving along a long, winding Boston road. She was going to buy a computer. At the end of any long trip, Beth would usually treat herself to a steak dinner.

That night, however, she had an overwhelming desire to treat herself differently: she would go to bed dressed as a woman. That night she walked into a boutique in Massachusetts and went shopping for a nightgown. She was 44 years old.

“I’m kind of different than most transgender people that you talk to,” Beth said. “I never felt anything as a child or anything like that.”

She doesn’t remember how she found The Breast Form Store, but Beth does recall that when she did, it took her two years before she bought her first pair.

Why? She says she initially had no intention of going through with a purchase. She denied Beth for a very long time. After finally trying on new clothes she bought for herself one day, she realized how good it felt. It was finally time.

“I wanted to get a pair of small forms that gave me the feeling of having breasts,” Beth said. “And I had to find one that fit me well. There was no way to sample them or anything like that.”

Breast forms come in all shapes and sizes. Do you prefer the adhesive or a breastplate? Do you want a more oval or triangular shape? Do you want to start off as an A cup? Maybe a D cup? What’s your band size? Are you 34 or 36 inches? It can be overwhelming, but Beth got through it.

“I just had question after question, and they never wavered in answering them,” Beth said. The profit from her purchase is in no way comparable to the time they spent on the phone guiding her, she said.

Eventually, she learned everything she needed to know. Saving up a couple of hundred dollars was the next big step. The average breast form can range from $100 to $300 and typically lasts for two years. Suddenly there were these new expenses she had to consider.

During this time, Beth started writing a book of poetry. She would wake up in the middle of night, write a few stanzas and go back to bed.

Now, Beth feels more settled. She has no intention of getting surgery. She’s 74 and on heart medication. And an operation can be costly.

It doesn’t matter though, because her breast forms fit her just fine.

‘There’s a lot of hatred’

It’s break time on the photo set. There are at least six boxes of breast forms in one corner of the room, and we’ve only gone through half of them.

Claire, the model, is clearly exhausted. She’s not trans, though she does spend some of her time advocating for LGBT rights. The store likes to use models with small, not-too-curvy frames so potential customers can accurately imagine how the breast forms will look on themselves.

Eden, a business support specialist, is carefully arranging the next pair of breast forms for the camera. She begins to scan the wardrobe and accessories. Every item is in place for the next round of photos. As today’s set director, she woke up early, threw on a top and a pair of loose fittings jeans and flipped through magazines, marking which poses she liked best.

Eden’s worked here for nine years. Beth sings her praises. It’s not surprising, given Eden was the one who spent two years with Beth on the phone. She knows the ins and outs of the business, and she loves it. But she told me that this job isn’t for everyone.

“When I was hired,” said Eden, “the job was listed on Craigslist. And it was described as ‘feminine hygiene.’ I found the website, but I assumed it was the wrong website because I was like, ‘This is not a tampon manufacturer!’”

There are a few simple explanations for these misleading job descriptions. Firstly, people often erroneously assume it’s a sex store. Needless to say, it’s not.

Secondly, these ambiguous job descriptions serve to weed out men. It’s harder to train men in this business, Oren tells me. They don’t understand bra sizing.

Lastly, but most importantly, trans people usually find women easier to talk to. It took Victor months before anyone felt comfortable talking to him. On the very rare occasion that Oren answers the phone, he’s met with the same click that his father experienced two and half decades earlier. Although men do work in the store, it’s just not in customer service.

With hindsight, Eden also sees why these job descriptions have to be worded very carefully. If the store states the facts too plainly, there are few to no responses. Sometimes applicants get to the final round, hear the full story and back out.

Eden stayed, even when things have been difficult. She’s heard her share of happy stories, but she’s listened to painful ones too.

“It is slowly changing,” she said. Society is becoming more open-minded and accepting of non-traditional ideas of gender identity and expression.

Yet Eden tells me that shipments still increase during the colder months. More layers mean customers can test their purchases undetected. They can be sneaked into the house under the guise of Halloween decorations, Black Friday sales and Christmas gifts.

If too much time passes before a customer’s next order, Eden gets anxious. She can’t call or speak to them about anything but their shipments. It’s company policy. Privacy must be maintained at all times.

But still, she worries.

“The transgender community is a very marginalized community. There is a lot of crime. There’s a lot of hatred. There’s a lot of murder that goes on, in terms of hate crimes for these women with no visibility and understanding.”

The cross-dressing community faces less crime, she says, but there is still very little support from family, friends and spouses. There’s a certain level of shame.

The job allows Eden to give back. She has fun helping new customers get dressed up and fitted in their new outfits. Despite all the sad stories, it’s her favourite thing.

As they’re wrapping up for lunch, I can’t help but take a peek at their pink fitting room downstairs. It’s decked out in wigs, clothes, shoes and all the necessities needed for a head-to-toe transformation. It’s a room with a bright personality.

I compare it to the bleak warehouse space adjacent to it. Stacks of breast forms on 12-foot-tall shelves. Messy workstations where the breast forms are created.

I think about how each pair is destined to be shipped to a new owner in the morning. Like Beth’s, maybe it will be someone’s first pair. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Gender + Sexuality

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: