“Baklava! Baklava!” he bellows.

You might’ve seen him around Vancouver. He’s a middle-aged Middle Eastern man with a greying moustache. About two to three times a week, for two to three hours at a time, the man sells baklava, sweet pastries, on the street. When he feels he’s sold enough, he vanishes.

His bravery and brazenness have inspired a faithful online following who anxiously await details of his whereabouts. Since August 2017, the Vancouver page of the discussion website Reddit has become the go-to place for sightings. “They are amazing,” wrote the user who announced his existence to Reddit last summer about the treats. “It’s kind of endearing.”

It’s not easy finding a street vendor on wheels — even food carts take to social media to share where they are for the office lunch crowd — so it’s no surprise that the appearance of the man is announced on Reddit like a weather warning.

And his fans have given him a name.

“Baklava man HERE NOW. He just arrived and is setting up (4:45 PM)”

There have been many passionate and obsessive discussion threads about the baklava man since, with over 1,100 comments and over 3,000 upvotes and counting.

Some of them are philosophical musings, the kind you can only find on the Internet: “What is man? What is baklava?”

Some of them are outpourings of love, the kind you can only find on the Internet: “Now just to clarify I am in no way a baklava expert but these were simply heavenly. Top tier. 100/100. This would be my request for my last meal if I were on death row. Yes, that good… I've been having dreams about this baklava and let me just say that these dreams were wetter than Vancouver.”

But who is the baklava man? He had a sign that read “Syrian family food,” so there were guesses that he was from Syria.

I ran into the baklava man three times before I discovered who he was.

I had a feeling he had an interesting story, but I could never have guessed its scope — that he hugged an American president, that he was a beloved figure in another part of the world or that he had a close connection to the tumultuous politics of the Levant.

The first time I saw the baklava man he was selling Arabic coffee on the edge of the sidewalk near Metrotown. He had a table with plastic cups and drink dispensers. There was no baklava for sale. This was October 2017.

The second time was near the Vancouver City Hall. I recognized him because of his moustache. He had no coffee this time. Instead, he was selling some kind of food in plastic clamshell containers. I didn’t pay attention to what was inside, but from the look of his setup, it wasn’t a licensed business.

The third time was on the edge of Chinatown in February.

“Baklava! Baklava!” bellowed a voice.

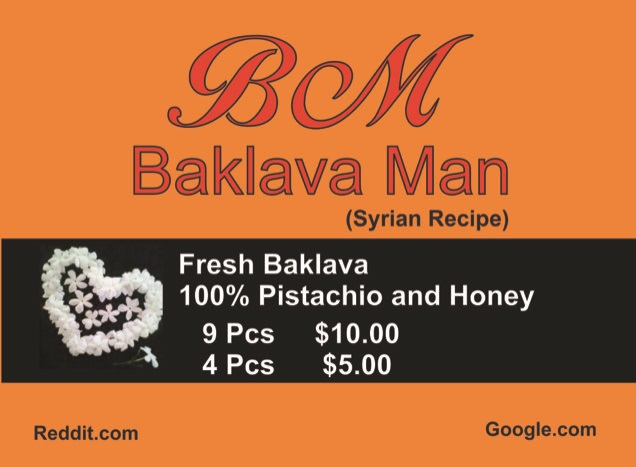

The moustache told me it was the same gentleman. He had a sign, a laminated printout with bold yellow letters, that read:

“Syrian Family Food

Arabic Buklava

100% Pistachios

With Honey

Taste Amazing

4 pieces for $5.00

9 pieces for $10.00”

Since the third time’s the charm, I decided to chat him up.

“Hello,” I said.

“Hello!” the baklava man said.

“How are you?”

“Good, good,” he said.

“Did you make these?”

“Yes, yes!”

When I tried to introduce myself, the baklava man tried to sell me baklava. I asked whether he was from Syria — pointing to his sign — but he again he tried to sell me baklava.

“English…” he said, then wiggled his hand to make the so-so gesture.

But his sign was in English, so I figured that there must’ve been an English speaker in his family. Perhaps I could try to get his home phone number.

“Phone?” I asked.

“Ah!” the bakalava man said. He fished a business card from his pocket and handed it to me. I thanked him and told him that I would call.

“Welcome! Welcome!” he said.

There was a name on the card: Al Homsi.

Before I googled for an Al Homsi, I searched to see if anyone else had noticed a man selling baklava on the streets of Vancouver. I quickly found his fans on Reddit.

“Got a box for the first time and definitely lives up to the hype. Not gonna share with my family hahah”

“he's an adorable little ol grandpa”

“where will he be tomorrow? Nobody knows!”

Some Redditors said they couldn’t see the baklava man’s permit and that he shouldn’t be selling food on the street without one. In response, someone replied, “Who gives a shit. If you’ve ever been to any non-western city, street vendors selling food are literally every 30 feet on the sidewalks.”

Since the baklava man had a business card, I googled his name to see if he had a brick-and-mortar store.

There was no one with the first name Al and the last name Homsi. But I found multiple headlines about a man named Mohamed-Mamon Alhomsi, everywhere from the CBC to Global News, the Vancouver Sun to the Ottawa Citizen. This Alhomsi was a refugee to Canada and a former independent Syrian parliamentarian. The headlines were from a viral December 2015 moment when Alhomsi had an emotional reunion with his sons at the Vancouver airport after they’d been apart for 15 years.

I instantly recognized Alhomsi from the picture. Mohamed-Mamon Alhomsi was Vancouver’s baklava man.

I called the number on the business card.

“Hello?” the baklava man said.

“Mr. Alhomsi?”

“Yes?”

I tried communicating who I was in simple words — reporter, newspaper, baklava — but the only word he responded to was baklava.

“How many boxes?”

“No, no!” I said. “I am a reporter. Newspaper.”

“Reporter? Newspaper?”

“Yes. I’d love to talk to you. Friend? Family? English?”

“Ah!” There was a pause. “My friend — English. He call you. Today.”

“OK! Thank you!”

“Welcome! Welcome!”

I decided to text him “Tell your friend phone me. Thank you!” in Arabic, with the help of Google Translate, just in case. I worried Google would fudge the message, but it turned out to be good enough that we didn’t need a human translator in subsequent talks and interviews.

Alhomsi had a good impression of Canadian journalists from the time that he’s lived here. “It is a noble profession,” he wrote me via Google Translate. He appreciated the empathy from journalists who witnessed the airport reunion with his two sons. “All the reporters were crying with me.”

I told Alhomsi that I was curious how a Syrian parliamentarian ended up selling baklava on Canada’s streets. Through my interviews with Alhomsi, English and Arabic news sources and information from NGOs, here’s what I pieced together of his life.

Mohamed-Mamon Alhomsi was born in Damascus on April 8, 1956. His father owned a leather dye factory. Alhomsi followed in his footsteps to become a businessman as well, importing cars from a Korean manufacturer called SsangYong.

But Alhomsi had more than business on his mind. He’s always had a passion for social causes. It was an unstable time. Syria was under emergency law, effectively suspending most constitutional protections for citizens and justified on the grounds of the continuing war with Israel and threats posed by terrorists. So in 1986, Alhomsi ran and was elected a city councillor of Damascus. Four years later, he was elected to Syria’s People’s Council, the country’s parliament, as an independent.

Trouble arose when Bashar al-Assad took the presidency in 2000. He was attending postgraduate studies in London when he was called to return to Syria by his by his father and longtime president Hafez al-Assad to succeed him in power, and his rule was the beginning of a bloody reign.

Alhomsi went on a hunger strike to protest Assad’s human rights abuses. Then on an August morning in 2001, nine cars showed up at his office. Thirty police officers and a senior official arrested Alhomsi, and according to the Arab Commission of Human Rights, the regime began a defamation campaign against him through its controlled press.

“He was highly respected and popular,” said Ayman Abdel Nour, who runs a popular news and opinion aggregate called All4Syria from the U.S. “He won the elections as an independent and was not appointed by the Assad regime — really elected, that means he was chosen by the voice of the people. That’s very, very rare.”

Nour is anti-Assad as well. He has a personal connection to the president: they were classmates at Damascus University and one-time friends, until Nour felt Assad did not have the interests of the people at heart.

Alhomsi was imprisoned for five years. When he was finally released in 2006, he fled to Lebanon with his wife. His 16-year-old son was kidnapped and held overnight in an attempt to lure him back to Syria. From Lebanon, Alhomsi lobbied foreign governments to support democracy and human rights for his people.

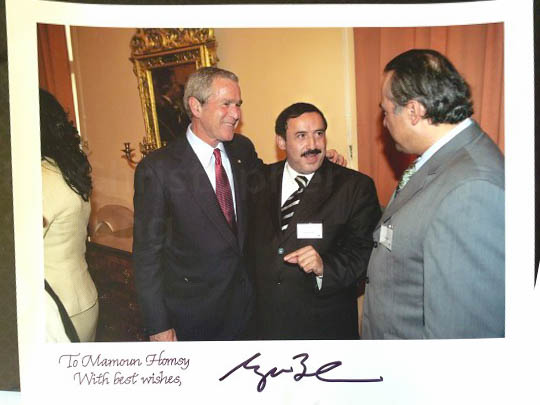

He had the opportunity to attend the Democracy and Security Conference in Prague in 2007. Then-U.S. President George W. Bush was also in attendance, and said he was “looking forward” to meeting democratic activists like Alhomsi.

“This man was an independent member of the Syrian parliament who simply issued a declaration asking the government to begin respecting human rights,” Bush said during his conference remarks. “For this entirely peaceful act, he was arrested and sent to jail, where he spent several years beside other innocent advocates for a free Syria.”

Alhomsi still keeps a signed photo of him and Bush from their time in Prague.

Not long after, Alhomsi was invited to the White House. Alhomsi says he was told he was the first Syrian to visit. He met with Bush for 55 minutes. “He gave me a big hug!” Alhomsi told me one day, laughing while he mimed a large embrace.

Alhomsi’s continued activism angered the Assad regime in Syria, which pressured the Lebanese government to expel Alhomsi from its country. Lebanon moved to deport him, but Alhomsi was able to register with the United Nations as a refugee.

“I had eight countries to choose from,” Alhomsi wrote me, “but Canada was my first choice because it had a good reputation of human rights.”

He arrived in Canada in 2010.

Today, Alhomsi lives alone. His sons live elsewhere. Alhomsi rents an apartment in an old concrete high-rise. Like 75 per cent of the region’s refugees, he lives in the suburbs.

“Expensive,” he told me.

Much of his savings was confiscated by the Assad regime. This is common for dissidents, said Nour of All4Syria news.

“They’re killed, they have their money confiscated, they escape — that’s all the options,” he said. “It happens to tens of thousands of people who stand against the regime.”

Alhomsi hopes for the fall of the dictator and restoration of his finances. Until then …

“No welfare,” he said. “I work.”

Last year, Alhomsi became the baklava man of Vancouver’s streets. One of his sons didn’t like the idea, but Alhomsi insisted on keeping busy.

At first he tried selling Arabic coffee and sahlab, a sweet, milky drink made from an orchid. Reception wasn’t stellar, or else he would’ve become sahlab man.

The treat most popular with Vancouverites turned out to be baklava, the pastry made of layers of filo filled with chopped nuts and honey. Alhomsi likes to add rose and orange blossom water. He said he learned how to make baklava from his cousin, whose family had a bakery for over 30 years.

Alhomsi bakes the baklava in huge trays at home and packs them in plastic containers. He stacks the containers in large cardboard boxes. He’s got a foldable shopping cart to wheel them around the city, which doubles as a display.

“I only need a metre of space,” Alhomsi wrote to me.

That and his warm, jolly personality.

“Baklava! Baklava!”

People who encounter Alhomsi for the first time are often amused. Those familiar with the baklava man greet him like an old friend.

Alhomsi’s also a trusting businessman. For customers who don’t have cash, Alhomsi has a policy of “eat now, pay later.” There aren’t many takers, because no one wants to feel like they were taking advantage of a mobile street vendor’s kindness. But those that take the offer are usually able to find him again and often leave a generous tip.

Aside from the business, Alhomsi has received great joy in return. He has nothing but praise for Canadians, especially the young Vancouverites who spend time with him on the sidewalk.

“They encourage me to continue my work,” he wrote me.

I was curious whether Alhomsi knew he was an Internet celebrity, so one day I sent him the Reddit threads about him.

His response: “There is a wonderful online campaign about my merchandise under the name of the baklava man.”

From Reddit he also discovered that someone created a listing in Google Maps of his business. At the moment, it’s got 4.9 stars from seven reviews. “Amazing, authentic,” reads one review. “Also has a neat laminated sign. Very nice.” If you look online, there is extensive discussion of his laminated signs.

Alhomsi was so pleased that he signed off that email as “the baklava man.” He even made a new sign with the name, and listed Reddit.com and Google.com on it.

Alhomsi doesn’t have a City of Vancouver permit for street food vending and said it’s been a challenge to attain one. He said he’s still trying.

For street vendors without permits, the city has a three-strike approach to enforcement. The first strike is met with education, letting vendors know how they can apply for a permit. The second strike is a written warning that if they continue to sell items, the city may impound their goods. On the third and final strike, the city may impound the items they are selling or the structures they are selling from.

Marginalized people in cities, like immigrants, refugees and the poor, often turn to the streets to sell items for survival, but this is especially challenging in North America. Cities have rules and regulations dictate what you can sell and where you can sell it.

“Every vendor will be told where to stand and every dog will be told where to urinate,” the late Vancouver civic politician and lawyer Harry Rankin once said about the city’s street vending restrictions.

Selling food on the street gets even more complicated. In Vancouver, requirements for street food vendors include a waste management plan, a business plan, a valid health permit and the ability to work in Canada legally.

It’s a challenge for marginalized groups like newcomers to sell food commercially if they aren’t familiar with the local language or local business know-how. As a result, a few organizations have stepped in to help Syrian refugees start cooking in their new home. In Vancouver, a social enterprise called Tayybeh hosts pop-up dinners cooked by Syrian women. And in Toronto, a non-profit called Newcomer Kitchen is doing something similar.

In March 2016, the Depanneur, a small café and food business incubator, invited the Syrian refugees living at Pearson airport hotels a chance to cook for their families.

“There were family members who said their children were losing weight because of eating all this strange food. It turned out to be chicken fingers and fries!” said Cara Benjamin-Pace, the executive director and co-founder of Newcomer Kitchen. “They were really missing the food from back home, so this really spoke to our hearts. Lot of women hadn’t had kitchens in the refugee camps, some of them up to four years.”

It led to a series of public dinners and now meals sold online for pickup or delivery, with proceeds shared among cooks. Newcomer Kitchen also helped pilot Toronto’s first Food Handler Certification in Arabic, paving the way for Syrian women of all backgrounds to work in Canadian kitchens.

“The demographics were very broad,” Benajmin-Pace said. “Everyone from older grandmothers who had lived in rural areas with 15 children who had never learned to read or write to PhDs, mathematicians, English majors who specialized in Shakespeare, Damascan socialites, lots of teachers, x-ray technicians and lots of stay at-home moms, too.”

Considering the diversity of Syrian refugees in Canada, perhaps it’s less of a surprise to find a Syrian parliamentarian selling baklava on the streets of Vancouver.

Sometimes I worry about Alhomsi because he’s running his enterprise alone. Though he’s quick to appear and disappear, he’s selling food on the streets openly. His public profile is also growing. After a month of conversations, Alhomsi wrote to me that “sympathy from Canadians gives me great assurance.” It is because of this that he’s willing to share his story.

Characters of sidewalks like the baklava man are nothing new in our cities. In Vancouver, a man locals called Santa sold clothes he hung on the chain link fence of an empty lot on Fourth Avenue off Macdonald. Vendors often pop up outside the SkyTrain station on Commercial Drive; one guy sells used paperbacks. You might have familiar characters like Alhomsi on the corners you frequent.

Crackdowns on street behaviours like vending are also nothing new. The city has been called the “quintessential police site” by Simon Fraser University geographer Nicholas Blomley. Urban sidewalks have always been places of contention and negotiation, grey areas defined by people and policies.

A former sociology professor of mine wrote about the history of the City of Vancouver’s attempts to eliminate street vendors. In the 1910s, it was mobile Chinese vegetable peddlers. In the late-‘60s, it was popcorn peddlers on beachfronts. In the 1970s, it was the “hippies” who sold beaded jewelry, leather goods and candles. These crackdowns are usually a reaction.

“Cities don’t often act until someone complains,” Amy Hanser said. “So it really is a complaint-driven process.” I took a class on the sociology of consumption with Hanser, who’s an expert in street vending, street food in particular, in China and North America.

Hanser said that different behaviours are met with different reactions depending on the neighbourhood.

There may be a neighbourhood where you can loiter for a long time without complaints. “In the Downtown Eastside, there’s a very high tolerance for people on the sidewalk,” she said.

There may be a neighbourhood where binners — individuals who collect recyclables to exchange for cash, a common phenomenon in Vancouver —– are tolerated, even welcomed. They may be shooed away in others.

And there may be a neighbourhood where street vending is accepted as part of the sidewalk.

“The specifics of how it works out are very, very local,” Hanser said.

If the world of a neighbourhood sidewalk is defined by every interaction on it, then how the baklava man gets treated is a litmus test for the community he happens to be in.

Today, Alhomsi is probably checking the weather app on his phone to see if it’s a good day to sell on the street.

He thinks of Syria often.

“My hope is that her tortured and displaced people return to freedom and democracy,” he wrote to me. “But I am honoured to be a Canadian citizen. This is my second homeland.”

It’s a challenging thing to communicate with someone through gestures and Google Translate. But I told him once that I was glad that we could have conversations despite the language barrier.

His response was befitting a popular politician.

“Love and humanity do not need languages.” ![]()

Read more: Food

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: