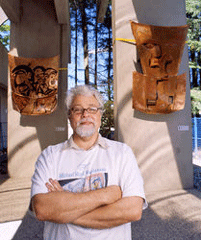

Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas has made a career messing with stereotypes about indigenous people. Now he's messing, as well, with the notion of what a museum is supposed to showcase.

Known for his Haida Manga, a unique art form that mixes Haida narratives and graphic forms with Japanese comic-book style, Yahgulanaas "has 50 ideas a day," says curator Karen Duffek. His three site-specific installations can be seen at the Museum of Anthropology on the University of British Columbia campus until December 31, 2007. The show is called Meddling with the Museum.

As patrons enter the museum, Coppers from the Hood, made from car hoods (two red and two white vehicles) welded together to echo two traditional copper shields, helps raise questions about whose land is it that the institution sits on. Decorated with real copper flake and Yahgulanaas's distinctive graphic-style, the pieces feature Haida manga characters whose antics flow throughout the show.

Bone Box uses discarded storage boxes that once held some of the museum's collections. Yahgulanaas turned them over and painted the other side of twelve panels that together resemble the front of the carved cedar chests displayed on platforms nearby. The location of this narrative collage is critical, says Yahgulanaas, because patrons can see a hint of something beyond. By turning copper cranks on the side, viewers can see past the piece to the ancient cedar poles and other monumental art taken from indigenous lands.

For Pedal to the Meddle, he flips a treasured Bill Reid canoe (also carved by Guujaaw and Simon Dick) upside down and ties it to the top of a Pontiac Firefly (named after the indigenous leader and an insect). The car, professionally painted with a mixture of auto body enamel and argillite dust, is perched on the ramp near Bill Reid's The Raven and First Men cedar sculpture in a getaway pose, complete with skid marks on the floor. In this way Yahgulanaas takes the notion of a sacred icon for a ride. "It looks like we're trying to steal the canoe back," says Yahgulanaas.

For all his commentary, Yahgulanaas is not against museums. He sees the culture of the institution, like all cultures, changing.

"Before it was just them taking and us complaining," he says. "But now there is more of an active conversation."

Curated explosions

Museums once were assumed to be shrines to the truth. More commonly these days, they are homes to controversy over whose "truth" gets told, and how.

Last month, angry critics forced wording changes in a National War Museum exhibit on the Canadian involvement in the fire bombings in Germany during the Second World War. Similarly, in 1995 in Washington, D.C., U.S. Air Force veterans hotly protested, and prevented, a planned exhibit at the National Air and Space Museum featuring the Enola Gay, the bomber that dropped an atomic bomb on Japan at the end of World War II. And five years previous, African-Canadians charged racism and organized demonstrations against the exhibit "Into the Heart of Africa" at the Royal Ontario Museum. The curator's intent was to question the imperialist ideology held by many Canadians during the Boer War when many of the pieces displayed were collected and to critique the act of collecting itself. But that intent was lost on the protesters, who forced the show to close.

Irony isn't universal

Dr. Anthony Shelton, director of the Museum of Anthropology, says controversial topics must be addressed if museums want to stay relevant. The challenge for curators, he says, is that they can't just tell a story and expect it to be interpreted the way they, as experts, expect it to be understood.

"Irony is not universal," he says of one reason for the ROM's "Into the Heart of Africa" debacle. The curator may have expected the written words to tell a different story, but some patrons don't read everything in the displays and others let the objects -- in this instance bounty taken by colonizers -- speak for themselves.

He says developing new projects can involve long series of consultations and not only that, museums need to go through a critical evaluation of their permanent exhibits from time to time to raise new points of view.

The MOA is now undergoing a $50 million renewal project. Not only are they increasing the size of the museum by 50 per cent, but they are reevaluating and redefining the way their collection can be accessed within the building and online.

Keep talking

Part of the ongoing conversations with indigenous communities at MOA revolves around changes to the visible storage display. When the museum first opened in the 1970s, this practice of pulling objects out of the dusty back rooms and putting them all on display was cutting edge.

But some have critiqued the displays like the big glass case of Hamatsa masks from Alert Bay, saying they look more like stacked firewood or a Value Village coat rack, says Duffek.

Shelton says that consultations underway now have revealed that each indigenous community has a different solution for how they would like their cultural objects to be shown. Some groups want the museum to show only the best pieces, he says. Others want objects categorized by ownership history, others ask that they be classified by names in their own language and still others would like to see the pieces shown in the order they would be seen in certain ceremonies.

Opinions also range in each community, even among the different age groups. In some cases, elders believe that masks and whistles used in the winter ceremonies should not be displayed at all. Traditionally, only some were allowed to see the objects. But others say, no, young people don't get to see these pieces in their traditional setting enough, especially those who live in urban centres.

Some young people are calling for a revitalization of traditional values and have the fiercest opinions about respecting old ways. Duffek says the museum is still struggling with what to do.

"These are internal community debates and we don't know how that will resolve itself," she says.

Community decided

Community consultation was key to this summer's reopening of the Haida Gwaii Museum in B.C.'s northern archipelago. The museum occupies a new space as part of the $25 million Haida Heritage Centre in Skidegate. New exhibits explore everything from food gathering and preparation to conflict and contact with Europeans to the Haida activism that helped turn the southern part of Haida Gwaii into a co-managed National Park Reserve and Haida Heritage Site.

"Everything in the centre comes directly from the community, even the words," says museum curator Nika Collison, who spent hours consulting with community members about how they wanted to share their culture with the world.

Although many modern pieces are on display, even ancient cultural treasures in the collection can be connected to living people through the Haida lineages that still exist today, she says.

The exhibits are only a part of what the centre has to offer. The Haida Heritage Centre includes an art and design school, a café selling traditional foods, and a performance space too. Collison says many young people are already at work at the centre and several community events were held there, even before the doors were officially opened.

"It's not just a display of culture, it is part of the culture now," she says.

'Danger of self-censorship'

Tim Willis, head of exhibits and visitor experience at the Royal BC Museum in Victoria, is no stranger to controversy over cultural debates. In his previous post at the Royal Alberta Museum, he helped develop a permanent aboriginal peoples gallery.

Although museum staff had been working with aboriginal advisors, controversy erupted when the museum (then called the Provincial Museum of Alberta) commissioned two artists of Asian-descent to paint murals depicting the history of aboriginal people in Alberta. The ensuing struggle to get things right brought the museum and the communities it was representing closer together, Willis says, and more people came to see the final result.

"The danger can be self-censorship," says Willis of whether museums decide to take on projects that might spark unexpected debate.

Even when things have been done "right," as when the Royal BC Museum worked with local Tsimshian leaders on a display of treasures collected by a powerful missionary in the late 1800s, old grievances were still aired about how the pieces had been originally collected and later bought at auction for exorbitant prices.

MOA director Shelton says his institution will hold a discussion series next year that will raise further debate about the practice all museums are built upon -- that of holding cultural property. For some museums, the repatriation of artifacts to cultural communities has already begun, he says, but the looting of archaeological and other sites around the world continues.

"It's a huge field of controversy," he says. "We want to be provocative, while also being respectful."

Related Tyee stories:

- Series: Reconciling with First Nations

How the 'New Relationship' is faring in the Fraser Valley. - Wiring BC's Native Villages

How the internet is changing life in First Nations communities. - The Art of the Politics of Art

What gets funded?

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: