Last month in Prince Rupert three poachers caught with 11,000 live abalone crammed into the back of their pickup truck were sentenced. It was the biggest bust of its kind in B.C.’s history, but did the punishment suit the crime?

Some people in the poachers' home town of Skidegate on Haida Gwaii say it wasn't nearly severe enough.

An as-yet unpublished DFO report speculates that Northern abalone, once a $1 million a year industry in B.C., will be extinct in coastal waters within 50 years.

Harvesting abalone has been illegal since 1990, when Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) put a total ban in place on stocks that reached near crash during commercial fishing heyday of the 1970s and 1980s.

Stan and Dan McNeil and their sister's boyfriend, Randal Graf, were each charged with three counts, two under the federal Fisheries Act and one under the relatively new Species at Risk Act, a hallowed piece of legislation which claims to offer protection to threatened and endangered aquatic species.

When the day of reckoning arrived, Stan McNeil, who has been charged with Fisheries offences before, received the stiffest punishment.

He was fined $20,000 and given a 12-month conditional sentence, six months of which could be served under house arrest.

The other two were fined $10,000 each and given four months conditional sentence, with three months served under house arrest.

All three men are prohibited from diving (that's how abalone are harvested), Stan for five years and the other two for two years each. Stan lost his boat (worth an estimated $150,000), his truck and his dive gear.

Judson Brown, who works in resource management, grew up in the same small community, going to the same schools as Graf and the McNeil brothers. He's one of the locals surprised by what he considers a light sentence. He notes that Stan McNeil may have lost his boat and some gear, but he didn't entirely lose his ability to make a living.

Brown wonders what happened to the man's commercial fishing licenses, potentially worth millions. And he can still buy another boat. "It's not that hard to do," says Brown.

Brown says if this was the case that was supposed to serve as a deterrent for future poachers, he doesn't think the judge went far enough. "Judges don't view resource protection in the same light as a bank robbery or an assault," he says.

Traditional food commercialized

"Live by the sword and die by the sword," says Captain Gold, a Haida elder who used to harvest abalone from the ancient village of Skung Gwaii at the southern tip of Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve and Haida Heritage Site. A whole generation of his people hasn't been able to eat the tasty mollusk due to the greedy harvest of the animals by legal harvesters before the ban, and further plundering by illegal poachers.

Captain Gold has no compunction about saying he isn't impressed with the way the Department of Fisheries and Oceans have managed the resource in the first place. When DFO placed a total harvesting ban on the fishery in 1990, fisheries managers hoped that the beleaguered abalone would recover. But habitat surveys over the last 10 years have shown that the numbers are not bouncing back.

Captain Gold points to the commercial sea urchin fishery, which saw an upsurge in activity in northern waters starting in 1990, right around the same time the abalone ban was put in place.

Abalone and sea urchins are found in the same habitat and both are harvested by diving. "If you can get $5 for a sea urchin and $30 for an abalone, which would you take?" he says.

He thinks all commercialization of Haida traditional foods has had a negative effect on Haida people's ability to harvest the abundance themselves.

Other sentences

Brian Jubinville is the supervisor of the Fisheries and Oceans Canada's Special Investigations Unit for Southern Vancouver Island. He has made abalone and catching poachers his own personal quest. He was near despondent when he heard how many abalone were found with Graf and the McNeil brothers when the poachers were caught near Port Edwards in February 2006.

On the day the sentence was announced, Jubinville was still digesting the punishment meted out. His initial reaction was disappointment.

It was an astounding number of animals, he said, and although Fisheries officers tried to take the abalone back out to the ocean after the seizure, he doesn't think many of them survived.

He pointed to recent poaching cases and the sentences involved as a reason for his concern.

In November 2004, David McGuire of Victoria was caught with 450 live animals and pled guilty to 13 counts of fishing for, possessing and selling abalone. He was fined $25,000 and given a 10-year diving prohibition.

Joseph Ho of a Vancouver seafood wholesale/retail company received a fine of $50,000 related to the same case.

Observers expected the case involving the McNeils and Graf, the first prosecuted under the Species at Risk Act, would be dealt with more severely.

Jubinville says it is difficult to say how much poaching is taking place in B.C., but most scientists think that poachers like these are responsible for the continued decline of the species.

Recovery projects

Something positive that can come out of the fines imposed on poachers is that the courts often dictate part of the money collected be donated to recovery projects.

The Bamfield Huu-ay-aht Community Abalone Project Society received $22,500 from a recent abalone conviction fine and this money has helped keep the project afloat.

The project, which has been underway since 2001, supports a hatchery and a reseeding project that raises Northern Abalone in tanks and then releases them into the wild ocean.

Society president John Richards says he has also been able to sell some hatchery-raised abalone to high-end restaurants in Vancouver and on Vancouver Island. The animals are very slow growing, and even though he has some five-year-old abalone, they are only an inch to an inch and a half in diameter. At a price of $8 to $10 wholesale for the small creatures, they are only suited to a very high-end market.

Return the shells

Both C Restaurant and the Sooke Harbour House, restaurants committed to serving local and sustainably-harvested foods, have bought abalone from Bamfield, but restaurant managers also face some onerous DFO regulations involved in selling a threatened species. All shells from the abalone served must be collected and returned to DFO, for example.

Richards knows the market would prefer bigger sizes and fewer regulations, but all he can do is wait. Meanwhile any extra income is helpful to his struggling hatchery.

Eating an animal out of extinction may seem counter-intuitive, but that's just one of the innovative ways researchers and other coastal project leaders are attempting to turn around the Northern Abalone's fate.

Another unlikely sounding project achieving success uses abalone condos. No, these aren't fitted with stainless steel appliances, but they are located in some prime locations, from a shellfish's point of view.

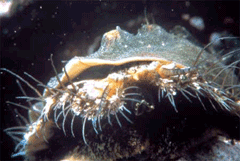

The Haida Fisheries Program is in its tenth year of monitoring local abalone populations. Abalone condos, an innovation of local marine biologist Bart DeFreitas, are artificial habitats that make finding juvenile abalone a heck of a lot easier. Abalone are nocturnal and like to hide in cracks and crevices, especially when they are small (sizes ranging from 11 to 109 mm).

By the end of 2006, 144 artificial habitats were in place and 900 "baby" abalone were counted in the waters around Haida Gwaii.

Related Tyee stories:

- Little Hope for the Ugly Fish

Demand for the toothfish has almost emptied the seas of it. - Save Our Oceans, Eat Like a Pig

Let's stop wasting tasty fish on animal feed. - When Money Buys Grizzly Lives

How good a deal was the purchase of coastal hunting rights?

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: