Avoid "dead water," the website advises, or else risk cardiovascular disease. According to Nanotechnology Limited, dead water is distilled or purified water that lacks minerals the body needs. The Chinese company claims that its product "nano water," currently available in Hong Kong supermarkets, is not only pure but has enhanced properties that fight inflammation, cancer and even aging itself. Thanks to a "nanometer high-energy water activator," this superwater has smaller molecule clusters that enable more direct absorption by the body.

Whether these claims are true or not -- scientists that I directed to the website pronounced it "hilarious" and "completely bogus" while company officials declined comment -- "nano water" is piggybacking on one of the most heralded scientific advances of our generation. Perhaps you've heard of the pants from Nano-Tex that repels spills or the Wilson Double Core tennis balls that have an extra nano-bounce. These are not exactly the stuff of scientific revolutions. But with advances promised in everything from cancer research to cheap energy, this technology of the tiny has a big future.

Nothing brings home the reality of a new consumer product like eating it. Nanofoods, currently a several billion dollar industry, is expected to grow to $20 billion by 2010. Most of this money is in packaging, but the food component may not stay under wraps for long. Nano-rice, nano-cheese, and hundreds of other products are in the research phase. Nano-agriculture, which relies on advances in microfine fertilizers and pesticides as well as microsensors for precision farming, is also just around the corner. Instead of waiting on the sidelines for the start-ups to work out the kinks, the big boys -- Kraft, Nestle, Campbell -- are investing large sums, putting their money where our mouths are going to be. Are nanofoods the best thing since sliced bread or simply round two in the "frankenfood" debate?

Defining nanotech

Maybe you read Michael Crichton's Prey, or caught the reference in Spiderman 2, or even played the video game Nanobreakers. Nanotechnology has permeated pop culture. Of course, so has Michael Jackson, and he too remains a mystery. Definitional confusion is endemic to new technologies, and nanotech is plagued by more than its share of misunderstanding. On the one hand, "nano" refers to any process that takes place at the nano-scale, which is 1-100 nanometers. A nanometer is one-billionth of a meter or one-thousandth the diameter of a human hair. A great deal of chemistry takes place at this level. Even ordinary combustion produces nanoparticles, whether from diesel engines or just plain campfires.

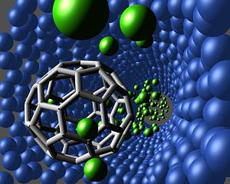

Strictly speaking, though, nanotechnology refers to scientific manipulations at the nano-scale. In the last twenty years, scientists have learned how to manufacture so many different synthetic nano-materials that they now have what amounts to a Lilliputian Lego set. These materials go by often fanciful names such as buckyballs (60 carbon atoms shaped like a mini-soccer ball), dendrimers (molecules that branch like trees), and quantum dots (semiconductor nano-crystals). The variety of these new materials is so wide that it can be difficult to generalize about their properties, just as it would be foolish to generalize about apples and oranges simply because they are both fruit.

Nanotech is often in the eye of the beholder. "If industry is selling nanotechnology to investors or potential customers, it says that the technology is new and unique," explains Kathy Jo Wetter of the watchdog ETC Group. "If industry is emphasizing nanotechnology's safety to smooth away concerns, it talks about the technology going all the way back to ancient Greece and about its use in medieval stained glass."

Sound familiar? In the debate over genetically modified organisms (GMO), the biotech industry claimed that their products were novel enough to warrant a patent but not so new and different to require a label or a special set of regulations. It might be more difficult for the nanotech industry to rely on similar arguments of "substantial equivalence." After all, what makes nanotech so potentially revolutionary is that materials often have very different properties at the nano-scale.

Definitional uncertainty is not the only problem to plague nanotechnology. To raise money, backers have hyped the new science's potential benefits. To lobby for regulations, the skeptics have played up the potential risks. These two worlds are just beginning to collide. The fallout will influence tomorrow's menu and determine whether both fast food and slow food are to be replaced, ultimately, by small food.

Food and money

No one in the nanotech industry wants to see a replay of the GMO experience: protestors burning fields, consumers waging boycotts, Europeans and Americans in a food trade fight, scientists calling into question each other's careers. The food and agriculture industry would like to avoid the mistakes it made with Calgene tomatoes (no one bought them) or Vitamin A "golden" rice (commercialization has been slowed by controversy).

The smart nanotech money so far has gone into packaging. German consulting firm Helmut Kaiser predicts that the new technology will transform 25 percent of the $100 billion food and beverage industry in the next ten years. "People's eyes widen when they hear that they can have a dot on a package that changes color when the food spoils," says David Lackner, a senior analyst with Lux Research. "Anyone who deals with the food chain and knows that spoilage accounts for huge losses knows that this little dot is a huge deal." Scientists have so far figured out how to shrink down these spoilage sensors but not yet shrink the price to make them commercially viable on a large scale.

Nanotech also promises a great deal in the realm of growing food. The smaller the particles of fertilizer, the greater the absorption by the roots of plants. The smaller the pesticide particles, the more easily it dissolves in water. Farmers might one day sprinkle "smart dust," or micro-sensors, over a field in order to transmit back information necessary to farm that particular soil with the precise combination of nutrients.

Whether "nano water" qualifies for the designation or not, nano-foods have begun to enter the food supply. The Food and Drug Administration has given the "generally recognized as safe" label to a synthetic lycopene from BASF that adds an orange color to food. Spray for Life, the first commercial product from Nanoceutical Laboratories Inc., relies on a new nanotech delivery system to make a vitamin supplement into a mouth spray. The Russians are feeding iron nano-particles to fish and reporting faster rates of growth, which has major implications for aquaculture. The Dutch are looking into how to use nanotechnology to shrink the fat globules in milk so that cheese melts more easily. Thai researchers are attempting an end run around GMO, which remains a hot-button issue throughout the developing world, by researching atomically modified rice that can be grown all year long.

Kraft, which set up a nanotech lab six years ago, is exploring nanocapsules that smuggle healthy fish oils into your chocolate chip cookies. A more visionary project involves customizing food with nanosensors that identify customer likes and dislikes and releases molecules that then change the smell and taste of the product. Kraft refused requests for interviews.

It's not just private money like Kraft and Syngenta and Monsanto behind this research. The U.S. Department of Agriculture has acquired a small piece of federal funding for nanotech, approximately one-fifth of one percent of total funding. This pales though in comparison to the Defense Department and its one-third share of the billion or so federal research dollars a year. The Bush administration is more interested in "smart dust" for gathering battlefield intelligence than farmland data.

The United States is ahead of all rivals in terms of nanotech funding. But other countries are closing the gap, particularly in East Asia. "When people look in the rearview mirror, they see Japan and China," says Lux's David Lackner. "Whether these countries are far away or whether these objects are closer than they appear is the question."

All of the federal research dollars and major corporate interest do not quite add up to "irrational exuberance." The first nanotech company to go public, Nanosys, couldn't get the $17 a share it wanted and withdrew its offering in August 2004. A company like Nanosys, with no commercial products, no profit, and not much revenue, might perhaps have been expecting a dot-com leap of faith. Even though Forbes publishes an annual "ten best" list of nano-products and several new nano-indexes have appeared on the stock market, investors are resisting the hype.

The greatest challenge to nanotechnology, however, is not the reticence of investors. As the GMO controversy reconfirmed, a new technology is only going to be profitable if people trust it and buy it. The number of scientific studies that raise troubling questions about nanotech is increasing. Neither voluntary nor enforceable regulations are in effect. The first protests against nanotech have begun.

"I'm very bullish on nanotechnology three to six years from now," says David Rejeski, director of the Foresight and Governance Project at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. "The benefits are spectacular. What worries me is getting there, the speedbumps. It's nice to have pants that repel stains but the stuff that really appeals to people is three to six years away. What happens in between is critical."

Health and safety

At the end of his May 31, 2005 Technology column in USA Today, Kevin Maney dismissed the health and safety concerns of nano-skeptics by arguing that "so far, no studies have shown that nanotech is harmful." But one month later, Maney was wondering whether nanotechnology might just be comparable to the fluoroscopes that shoe stores once used to X-ray customers' feet and that inadvertently exposed their sales staff to dangerous levels of radiation.

Contrary to Maney's initial claim, the last two years have witnessed a flurry of studies suggesting that nanotechnology is not as benign as first thought. This research has shown that carbon nanotubes have caused lung damage in mice and can in large quantities penetrate human skin to cause irritation. Buckyballs have caused brain damage in fish, might knock out smaller links in the aquatic food chain, and turn out unexpectedly to dissolve in water (which might inhibit the growth of important soil bacteria). Dendrimers, used in drug delivery systems, can punch tiny holes in and ultimately destroy cell membranes.

These studies are far from conclusive, particularly when it comes to the consumer. "I'm looking at my computer screen. It contains a lot of things that I wouldn't want to eat or rub on my skin, but those things are locked in there," explains Kristen Kulinowski, a chemist and executive director of Rice University's Center for Biological and Environmental Nanotechnology. "If you have nanoparticles that are bound in a plastic, then the potential of exposure to these materials is limited for the consumer."

But, Kulinowski continues, consumers are only one part of a product's lifespan. The health and safety impact of nanotechnology first hits the workers in the factories. The first cases linking asbestos to lung disease were among textile workers. Nanotechnology not only produces a new set of particles but also involves some old toxic risks as well. Says the Wilson Center's David Rejeski, "The idea that this is super-clean manufacturing, moving atoms around, that's not right. The input chemicals are not clean. A lot of this stuff is done by milling and it's really dirty."

At the other end of the chain, the "end of life" question, no one really knows what happens to nanoparticles. "What happens to all that nano-sized titanium oxide in skin care products when you wash it off?" Rejeski wonders. No one knows if nanoparticles accumulate in human tissue or ecosystems and whether nano-pesticides might pose some future DDT-like problem.

At whatever stage in the life cycle of these nanomaterials, their novel properties have yet to register on the radar screens of regulators. Ray Pimentel is Vice Consul for Trade at the British Consulate in Chicago. "If you look at aluminum, at the macro level, it's stable. But if you take it down to under 80 nanometers, it can be explosive," he points out. This crucial distinction is lost on those who monitor imports and exports. Pimentel continues: "Currently, an MSDS -- a material safety data sheet -- for nano-aluminum can just say aluminum. Even most aggressive nanotech advocates agree that that should not be the case."

Some nanotech firms are pushing for change from the ground up. Nanotool company Zyvex has established a certification program for carbon nanotube producers. "It's in their interest to deal with environmental health and safety issues," Lux's David Lackner says. "It also deals with the issue of buyers who buy a certain quality of nanotubes, but don't get the quality they pay for." Corporate self-interest has also been piqued by major insurance companies, such as Swiss Re, that have worried publicly about liability issues if some of the new nanomaterials turn out to be this generation's thalidomide.

Unlike the GMO issue, there has been greater dialogue between corporate, environmental and governmental stakeholders on the issue of regulations. A June 15 op-ed by Fred Krupp of the Environmental Defense Fund and Chad Holliday of Dupont in the Wall Street Journal tried to find common ground between voluntary standards from industry and enforceable regulations from government. The Environmental Protection Agency has recently begun to assess the usefulness of such voluntary regulations.

But the EPA initiative is not necessarily a step in the right direction. Jennifer Sass of the Natural Resources Defense Council worries that industry will get its way on voluntary, rather than enforceable, regulations. "Having these kinds of joint partnerships and collaborative efforts is a good thing," she says, "But without an overhanging enforceable regulation, I'm quite confident that the voluntary initiatives are inadequate regulations."

Other participants in the nanotech debate, like Hope Shand of the ETC Group, are looking beyond environmental, safety, and health issues to underlying questions of ownership and control. The slowness of the regulatory process has done nothing to affect the race for intellectual property rights. "We keep hearing the industry say that nanotech is in its infancy," Shand says. "But we're already seeing patent thickets in some areas that are creating barriers to entry for researchers in the global south. To get involved, they'll have to pay multiple licensing fees just to get started -- and that's if the companies want to give licenses."

Public Concerns

THONG is not waiting for industry and government regulators to get their act together. In May, Topless Humans Organized for Natural Genetics -- better known as THONG -- took off their clothes at an Eddie Bauer store in the middle of Chicago to protest the nanopants on sale. Printed on the rear ends of some of the protestors was the title of Richard Feynman's lecture that opened up the nanotech field back in 1959: "There's Room at the Bottom."

"Nanotechnology has been billed as the greatest thing since sliced bread: it will end global warming, cure cancer, and otherwise make the universe perfect," said one THONGster, who goes by the moniker of Just Joking Jerry. "When we see hype like that, our radar goes off -- another miracle technology that hasn't been adequately tested. So we're addressing hype with counter hype. We're getting in on nanotech on the ground floor. That was the big problem with GMO. We didn't get in quickly enough before the food crops were infected."

David Rejeski of the Wilson Center has been conducting focus groups on nanotech. He's found that the vast majority of people know next to nothing about the subject. More troubling, at least from the point of view of industry, is that the more people learn, the less trust they have. "In this country there's a tendency to use this efficiency model: if the public understood the science then they would trust us," Rejeski says. "But that's a dangerous track to go down."

Nanotech holds a great deal of promise and has more far-reaching applications than GMO. But with often unlabelled products in a largely unregulated environment, nano might fall into the same trust gap. Industry spokespeople are saying that small is beautiful. But consumers may not be ready yet to step up to the counter and say, "nano-size me."

John Feffer is working on a book about the global politics of food. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: