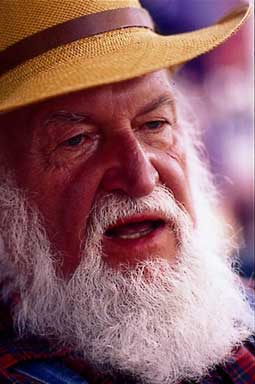

Utah Phillips is on stage seven on Saturday afternoon, winding through a folk song, which for him involves stopping at every opportunity to deliver vaudevillian humour and folk wisdom that have nothing (and everything) to do with the song at hand.

"In a mass market economy, a folk song is any song you choose to sing yourself," he says. He encourages the audience to sing (you are the folk, n'est pas?), then launches into the chorus of the Carter Family's "Railroading on the Great Divide." Some folks actually join in.

People should sing, and music should come from them. These are just a couple of things that Utah Phillips gets about the Vancouver Folk Music Festival, which operates resolutely outside the strictures of the music industry. It does so much to the chagrin of some critics, who look east at the "names" at festivals in Edmonton and Winnipeg and wonder why they never come here.

Utah Phillips stops again, and delivers another homespun observation. "It's comforting to know there are some things in the 21st century that don't change very fast; I am one of those."

The folk fest is another. It's been 27 years since Vancouver first welcomed artists from across North America and around the world for a weekend in a park. Bruce Cockburn, Odetta and Phillips were there that year, and this year they're back, reconnecting the festival to its roots.

Mostly, though, the festival has been consistent not in its names but in its outlook.

There's festival veteran Martin Carthy, a central figure in the revival of the British folk tradition and the most influential guitarist you've never heard of. There is the debut of East Vancouver's Leaky Heaven Circus, conceived over a bottle of wine in a working-class neighbourhood kitchen. There's grassroots spoken word and hip-hop refracted through the lense of punk. There's Eric Bibb, who brought his folksinger dad Leon onstage with Odetta to rekindle the magic they brought to Greenwich Village in the 1960s. There's the cultural collision of Autorickshaw. New takes on old Polish songs. A Mexico City dance band. The beatnik-hippie activist meanderings of Wavy Gravy.

There's guitarist Kevin Breit, whose distinctive tone enlivens Norah Jones's Grammy-winning debut CD but whose real accomplishment is his central role in the community jazz casserole that heats up on Monday nights in Toronto's Orbit Room.

At the festival, it's how you make music that matters most.

'Prisoner of optimism'

Phillips, who once refused to let Johnny Cash record his songs because he didn't want the music industry's tainted money, stops singing again. He declares that the revolution is people "seizing control of the things they already own."

He quotes Joseph Campbell: 'All we ever want to do is to be completely human and in each other's company.'

He quotes Mark Twain: 'Loyalty to the country always, loyalty to the government when it deserves it.'

He quotes Desmond Tutu: 'I am a prisoner of optimism. There are too many people doing good things for me to afford myself the luxury of pessimism.'

He quotes Ammon Hennacy, who taught him about pacifism at Salt Lake City's Joe Hill House, back when Phillips was a veteran recovering from the Korean War. Hennacy never went to the polls, Phillips recalls, but you couldn't tell Hennacy he hadn't voted. He'd just say: " 'I just didn't assign responsibility for other people to do things.' "

Phillips describes Hennacy's pacifism as something that goes far beyond the issue of violence, then quotes him again " 'You've got to give up the weapons of privilege and go into the world completely disarmed.' "

'Almost lost moral compass'

On Sunday at Jericho Beach Park, under a willow tree by the media tent, Phillips talks about getting arrested the day the war in Iraq began. A thousand people in his conservative county of 2,800 arrived at lunchtime at Nevada City, California's one significant intersection. They sat down. Then they negotiated the arrest of as many people as could be fed at the county jail.

Utah Phillips doesn't tour much at 69. Congestive heart disease keeps him in his Nevada City cottage full of books. But he still makes time for the important stuff, and thankfully that also includes coming to the Vancouver festival more often. He's become a sort of a godfather to the event; his philosophy is the festival's philosophy.

And at the core of it is the notion that music connects us to our communities and their histories. Phillips laments that we are losing our old songs. And he worries that new songs are made only to be heard by the public, not to be sung by them.

"I can't speak for Canada, but America is an ahistorical culture. We have a very short memory. I'm fond of saying a long memory is the most radical concept in the world. The long memory has been truncated, as we are leapfrogged by the mass media from crisis to crisis."

He sees oral traditions as a way to connect ourselves to the most human aspects of our past -- aspects the marketplace would prefer we forget so that we will buy something "new." "That's part of what I'm in it for, is to in my own small way restore part of that long memory."

Resisters and volunteers

Right now, that long memory is particularly important, as the marketplace tries to sell us a new war.

"Being a soldier in Korea," Phillips says, "taught me that I will never again do what I'm told. I almost lost my moral compass. I had to fight like hell to get it back." He says military training instills "the unhesitant response to a command." And while he understands that's what militarism requires -- he even longs for the camaraderie that only soldiers have -- he knows its cost.

That's the strength of his pacifism, and it also underpins his anarchist beliefs. "We grow up in a highly coercive culture." Phillips wonders why a man walking past us chose to wear identical socks when he woke up. "That's cultural compulsion…. We are locked into involuntary combinations, coercive combinations, boss-employee combinations, marital combinations…"

Anarchism, Phillips says, asks us to become self-governing enough to make voluntary combinations. "If you and I can agree to do our share of the work in this world, if you and I can agree to take only what we need and put back what we can, if you and I can agree to care for the afflicted, if you and I can agree not to hurt anybody, if you and I can agree to in some small way to get the work of the world done without the boss and the state, that's anarchism."

There is, at the Vancouver Folk Music Festival, that refreshing kind of anarchy. The festival has its own brands of cultural coercion, of course, although they tend toward the idiosyncratic and benign. But there is a startling array of unusual voluntary partnerships.

The festival wouldn't be possible without nearly 1,000 volunteers. It's no accident that the festival's current artistic director, Dugg Simpson, was once the volunteer coordinator. And the festival's most memorable moments are inevitably those when disparate styles voluntarily collide -- a Portuguese all-male choir with black gospel ensemble, Scottish pipes and Japanese drums.

Odetta's Sunday service

There is a sense at the festival that people acting together in unlikely combinations of their own volition can accomplish great things. Phillips believes that right now in the United States the movement to kick George W. Bush out of the White House is unstoppable -- because of what he's seen firsthand, at an intersection in Nevada City, for example, far from the mass media's radar.

As the festival wound down on Sunday night, another voice of history, Odetta, took the stage and did something that even Phillips couldn't do. She used her old-schoolteacher charm to get almost everyone in the audience to sing aloud. There was a sense that the Canadian crowd, always ready to compulsively applaud but reluctant to raise a collective voice, was only briefly and slightly ashamed.

"This little light of mine, I'm going to let it shine," we sang. It was anarchy, plain and simple.

Charles Campbell is a contributing editor to The Tyee. For a lengthy interview with Utah Phillips in September of 2003, go

here. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: