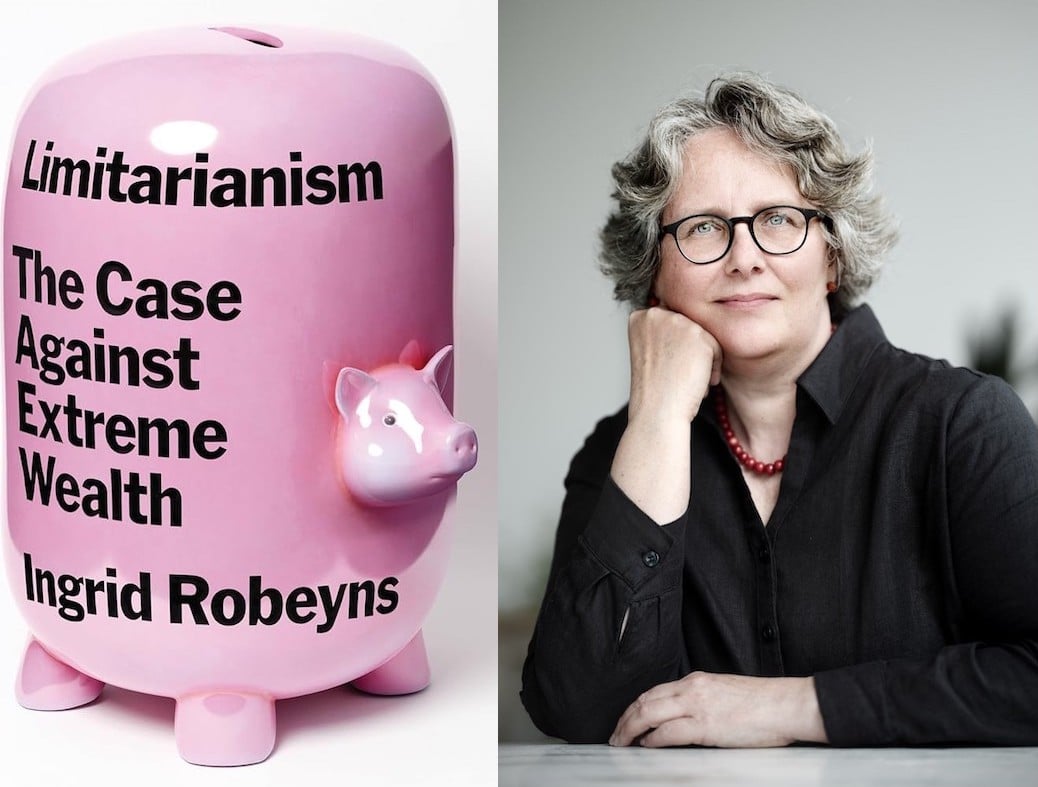

- Limitarianism: The Case Against Extreme Wealth

- Penguin Random House (2024)

“Eat the rich” may be an attractive idea to some, but let’s face it: the rich are just too few to go around. Their wealth, on the other hand, offers plenty for all.

Instead of fretting about a minimum wage for the poor, let’s set a maximum wage for the rich. Call it a million dollars a year, salary or investment income, with any excess income going straight into tax revenues.

It’s a sign of our oligarchs’ power that such an idea is almost unthinkable. But Ingrid Robeyns, a philosopher and economist at Utrecht University in the Netherlands, explores in detail the idea of limiting private wealth. In her new book Limitarianism: The Case Against Extreme Wealth, she makes a persuasive case and raises some very serious moral, political and economic problems.

The idea of limitarianism, as Robeyns defines it, is that no one needs or deserves more than enough income to live comfortably and securely. At present, she estimates, the local equivalent of a million dollars, pounds or euros should be plenty. Moreover, those making much less than a million would still live quite well thanks to social programs funded by taxing the super-rich.

In fact, such taxation would be simply retrieving the money the super-rich have stolen from us since the 1970s. “Trickle-down” economics actually pumped trillions of dollars out of the working and middle classes and up into the bank accounts of the 0.1 per cent.

Rich, thanks to dumb luck

The neoliberal takeover that began 50 years ago has now instilled in us the false idea that our personal success or failure should be measured in wealth, and derives from our own hard work or the lack of it. Robeyns argues that sheer luck determines wealth or poverty. Put Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk on a desert island, and they’ll be lucky just to survive. Put them in North America in the 1990s, when the taxpayer-funded internet has just gone commercial, and they’ll become billionaires.

Much great wealth has been dubiously acquired. Even under today’s laws, Robeyns says, much of the billionaires’ money is dirty — the proceeds of tax evasion, tax avoidance and plain crime. For example, an international tech corporation may make huge profits in Canada but pay nothing if it declares those profits in Bermuda, which has no corporate tax.

But it might be hard to find the line between dirty and clean money. Robeyns doesn’t mention the wealth gained by tobacco and alcohol corporations, or the makers of ultra-processed foods, or the fossil fuel corporations. She does mention the Sackler family, who gave the world OxyContin and the ensuing opioid disaster. Robeyns argues that the Sacklers should not have kept a single dollar made from such opioids.

Similarly, Robeyns says the bankers who caused the 2008 financial crash should not have been rescued by the taxpayers to the tune of $500 billion: “As the saying goes,” she observes, “‘socialism for the rich and capitalism for the poor.’”

“Capitalism for the poor” also means the poor pay far more than their fair share of taxes. And since the rich are taxed so lightly, governments find they must cut back on social services like health care, public education and environmental services... until they can be outsourced to the private sector, which can make easy profits from diverted tax revenues.

How to acquire $84 trillion without working

The situation is likely to get even worse. Robeyns cites an American financial advice service that predicts “that, among high-net-worth individuals (those with more than $5 million available for investments), a staggering $84 trillion will be transferred to the next generation by 2045. This massive transfer of assets from one generation to the next will see wealth inequality increase significantly in the decades to come.”

She then cites D.W. Haslett, a philosopher who said that if we have abolished the inheritance of political power, it makes sense to abolish the inheritance of economic power as well.

Ordinary people really have no concept of how rich the super-rich are. Robeyns cites Sir Leonard Blavatnik, who in 2021 was ranked the richest man in the United Kingdom thanks to his total wealth of £23 billion. Robeyns offers a thought experiment: “Suppose you work 50 hours a week, between the ages of 20 and 65 — week in, week out; year in, year out. How much would your hourly wage need to be so that, by the end, you’d have amassed £23 billion? The answer is £196,581 [C$334,056] for every working hour for 45 years.”

Robeyns offers a very useful explanation for the super-rich: the wealth defence industry. It was originally defined as a body of well-paid accountants and tax lawyers, dedicated to protecting and increasing the wealth of the top 0.1 per cent (and being very well paid for their efforts).

But the wealth defence industry also includes most political parties, media corporations, think tanks and even the justices of the U.S. Supreme Court who accept gifts and vacations from billionaires. Thanks to wealth defence, the ultra-rich can minimize their taxes (or pay none at all). Deprived of much of the tax revenue they should have, governments even lack the resources to go after tax cheats, much less provide good health care and education.

Moving the Overton window far to the right

Wealth defence has effectively moved the Overton window of political discourse and economic policy far to the right. What was perfectly good politics in the 1960s, like Medicare or affordable post-secondary education, now looks politically impossible because the cost would fall on the long-suffering taxpayer — not on the super-rich.

It’s easy to dismiss limitarianism because the super-rich and their money are highly mobile, so they can avoid serious taxation. Elon Musk didn’t like a Delaware court ruling that cost him a $56-billion pay package, so he’s moving his companies to Texas and Nevada. He could move a lot farther, to Bermuda or the Cayman Islands or Liechtenstein, if such tax havens beckoned.

Robeyns is very aware of that, and offers no promises of sudden global transformation. Instead, she suggests reform would be a “patchwork” of steps where a particular country might boost taxes, bring in extra tax revenue and start building up social services. Even that would take careful preparation. “The first and perhaps most important action limitarianism requires,” she writes, “... is to dismantle neoliberal ideology, because it is at the heart of the problems we are facing.”

Many of the super-rich are already demanding to be taxed more, and those who fled to tax havens would be stigmatized (and boycotted) as tax dodgers. They could also suffer the kind of sanctions we now impose on Russian oligarchs, or even see their property nationalized by unsympathetic governments.

Born with a savings account

A universal basic income is one way we might redistribute taxes on the super-rich, but Robeyns points to other possibilities. If all Americans paid the taxes they should pay, she says, “it would mean that the government’s budget would increase by $470 billion. Or, with just above 74 million children currently under the age of 18, it would mean that the U.S. government could open a savings account for each child, and deposit $6,350 in it every year. Each American child would find about $115,000, plus interest, in their account on the day they turned 18.”

So equipped, young people could afford college or trade school, or start a business, or become artists. Employers would have to boost wages or otherwise improve the dull, low-paying jobs young people are now stuck with. (Robeyns says unions should be encouraged, and union-busting be made a criminal offence.)

Another option would be a year of paid national service for everyone, perhaps on high school graduation. It would enable young people to see new parts of the country and to mingle with people unlike themselves. The rich especially live sealed off from the rest of their fellow citizens, and it would do them good to meet some poor ones — at least until inheritance taxes and universal basic income end class segregation.

“In a limitarian society,” Robeyns says, “you would still have the opportunity to be CEO of a major international company, but you could no longer earn millions on a yearly basis.... But this is the price we pay for the massive opening up of opportunities for all other groups, and for making our societies more just.”

The rewards of such high-ranking positions would not be measured in income or amassed wealth, but in status: tech bros would brag about the vast sums they’d created for the public, not just for investors. Similarly, Taylor Swift, who currently earns $150 million a year and has a net worth of $1.1 billion, would make just a million a year and would see most of her wealth taxed away — much of it to the benefit of Swifties. Her artistic success would be measured by record sales and concert attendance, not by the $150 million worth of real estate she owns.

“The question we should be asking,” Robeyns writes, “is not whether we should have capitalism or socialism. It is, rather, which specific mix of markets, regulation, distribution, government ownership, private ownership and collective ownership should we have? Making the decision to move towards a new economic system means choosing a new set of rules and institutions. It is essentially a political decision. Choosing these rules and institutions can only be done once we have determined what our collective wants and needs will be.”

Seen through Ingrid Robeyns’ eyes, wealth is a public good, like clean water. In times of drought, we don’t let some people die of thirst so others can fill their swimming pools. Similarly, we could share out the money we make so everyone has enough, and no one goes without. Not even Elon Musk. ![]()

Read more: Books, Rights + Justice

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: