Vancouver’s oldest workplace has lived many lives.

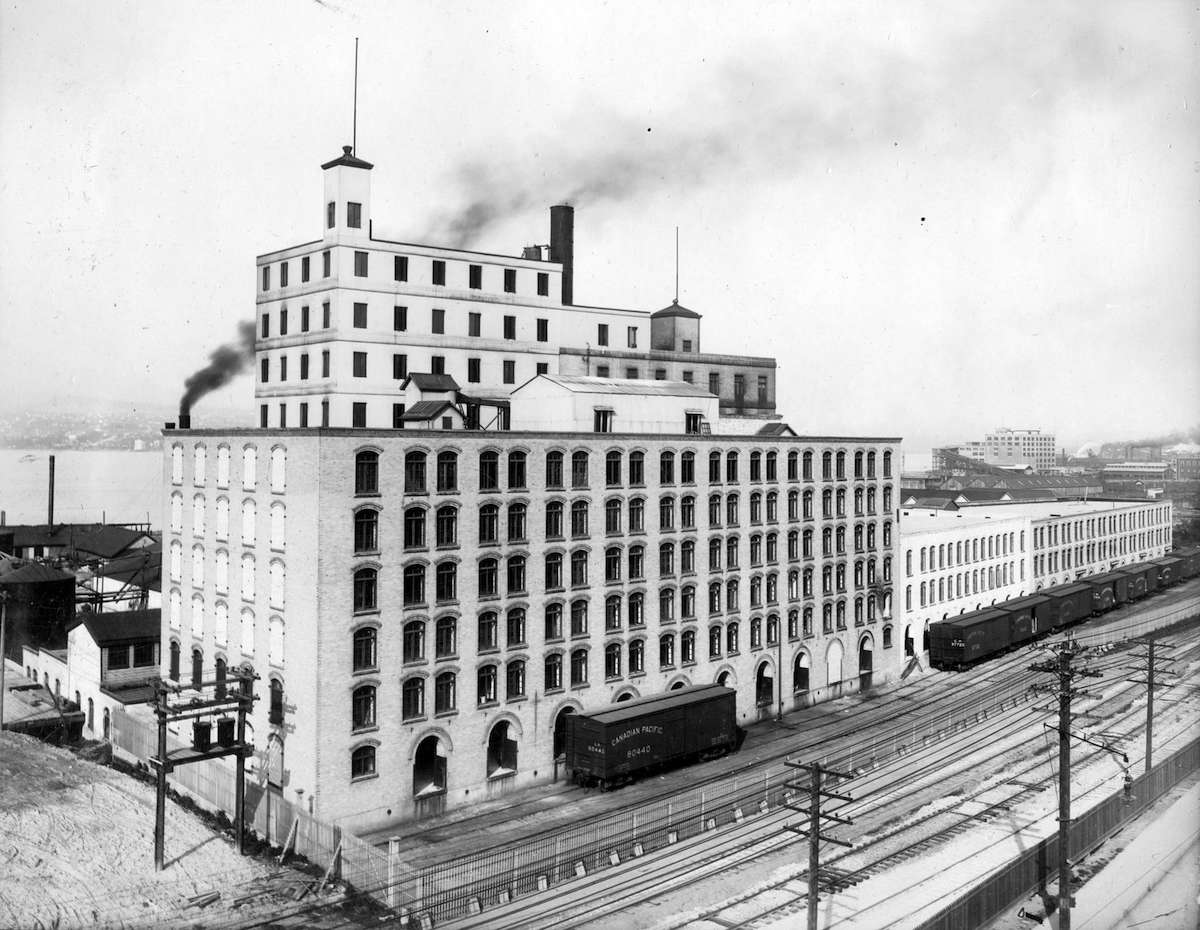

The city had existed for just four years when the Rogers Sugar refinery began to rise on the waterfront in 1890. For more than a century, this grey monolith has processed sugar cane brought in barges from the Pacific and Caribbean, feeding the local economy and a public hungry for the sweet stuff.

If you live in Vancouver, you’ve probably noticed its looming exterior while driving along Powell Street. And you may have seen its interior on TV: the building enjoys a second life as a popular film set, often cast as the sinister warehouse where the daring superhero confronts the villain.

But the Rogers Sugar refinery also holds other stories more bitter than sweet.

For decades, the sugar cane brought to this refinery was grown and harvested by indentured servants on faraway plantations, including one owned by the Rogers family and business partners. Workers at such plantations often endured whippings, beatings and malnutrition, and many died.

The refinery, meanwhile, has been the site of more than one pitched battle between its owners and the labour movement. In 1917, for example, the refinery’s founder, Benjamin Tingley Rogers, broke a strike by hiring replacement labourers and detectives. And just this year, workers spent roughly four months on the picket lines through rain and sleet before coming to a deal with the company.

At the heart of it all is this grey building on East Vancouver’s waterfront, where the sugar is still flowing 134 years later.

The ugliest building in Vancouver

The Rogers Sugar refinery was never considered a beautiful building. In 1975, the Vancouver Sun named it the single ugliest structure in the city. “For sheer force of its industrial ugliness, it could not be beaten,” the paper wrote.

But the building’s roots are very much connected to the colonial founding of the city itself. After the Canadian Pacific Railway was completed in 1885, sugar to feed its population was shipped from across the country.

That’s where B.T. Rogers saw an opportunity. On a trip to Montreal in 1889, he got wind of new development in Vancouver and believed the city would soon be an important industrial centre.

Donica Belisle, a professor at the University of Regina and the author of the forthcoming book Canadian Sugar and Indian Indenture in Colonial Fiji: Imperial Capitalism and Global Injustice in the Twentieth Century, says Canadian officials were only too happy to help him.

In exchange for building his warehouse, the City of Vancouver gave Rogers free land to build the site, which was worth about $30,000 at the time. They also exempted him from taxes for 15 years and gave the company 10 free years of water usage for its refining operations.

“When Rogers was established in 1890, Vancouver was only just starting to industrialize. There was a lot of investment coming from Montreal and New York,” Belisle told The Tyee.

It didn’t hurt that some of Rogers’ biggest backers had also funded the CPR. “They saw it as connected, because Rogers would send its sugar out on the rails through Western Canada,” Belisle said.

Racism and indentured labour

The Rogers refinery was and still is the only major sugar refining operation in the province. But Rogers had competition from some Victoria businessmen who imported refined sugar from Hong Kong.

The railway that made Rogers’ business viable had been built, in large part, by underpaid Chinese workers, but that didn’t stop him from playing into rampant anti-Chinese racism in a bid to beat his competitors.

A 1914 newspaper ad in the Vancouver World urged consumers to buy sugar “refined by clean methods, by clean white men.” The ad described Hong Kong refinery workers in extremely racist and offensive terms.

The sugar business had also long been entrenched in forced labour. Soon, Rogers got into that business, too. In 1905, he and a group of business partners founded the Vancouver-Fiji Sugar Co., whose purpose was to buy and maintain a plantation on the Pacific island to supply sugar cane to the Vancouver refinery.

Belisle says the business benefited from the First World War, which led to widespread inflation in sugar costs. “They were elated to sell their Fiji sugar on the world market and make profit out of that, and that’s what largely kept them going through the war,” she said.

But the Vancouver-Fiji Sugar Co. wasn’t to last. It was never able to produce a stable supply of sugar, and by 1925 the company had ceased operations. Rogers would go on to source sugar from other places, including contracts with plantations in Cuba and the Dominican Republic.

That short-lived company’s most lasting legacy is the misery it inflicted overseas, Belisle said. Even as Rogers’ company extolled the supposed virtue of well-paid white labour, it relied largely on indentured Indian workers to harvest Fijian sugar cane.

“They were indentured people from India, adults and children. They were treated as enslaved people,” Belisle said. She added that plantations were “places of violence.” Many workers died of beatings or disease.

This is a history that is rarely acknowledged in the Lower Mainland, which is incidentally home to one of the largest Indo-Fijian diasporas in the world. Rizwaan Abbas, an Indo-Fijian archeologist and historian, began diving into the history of his own community when his father passed away three years ago.

The history — and trauma — of indentured and slave labour runs deep, Abbas said. But few are aware of the specific connection the Rogers family has to it. Abbas does not know, specifically, if any members of the Indo-Fijian community are descended from indentured servants at Rogers’ plantation. But he said virtually every member of the community traces their lineage back to similar places.

“My great-grandparents were indentured labourers. So the trauma they faced from that episode of their lives was passed down to my grandparents and my parents and then passed down to me,” Abbas said. “That’s something the community itself has to deal with.”

The sugar business had a much sweeter outcome for the Rogers family: it made them wealthy. B.T. Rogers used part of the family fortune to construct the family’s mansion, which still sits in the West End.

The Tyee reached out to Lantic Inc., the Rogers subsidiary that operates the refinery today, with a request to comment about the company’s previous connections to indentured labour. The company did not reply by publication time.

Abbas said he wishes the company would acknowledge this chapter of its history.

“It’s a travesty that Rogers made so much money off the backs of indentured labourers. and I think Rogers should at the very least acknowledge the contribution that the Indo-Fijian people have made to the company,” Abbas said.

“That is something that I think is important, to have that acknowledgement. I don’t think they’ve ever done that, let alone apologized for the atrocities that they themselves have committed.”

Aboard a yacht, Rogers tried to crush a strike

Rogers claimed, frequently, that the exclusively white workers at the Vancouver refinery were well paid and well treated.

But popular accounts said otherwise. In 1911, the Victoria Daily Times ran a story titled “Alleged Baking Horrors in City,” detailing cramped working conditions.

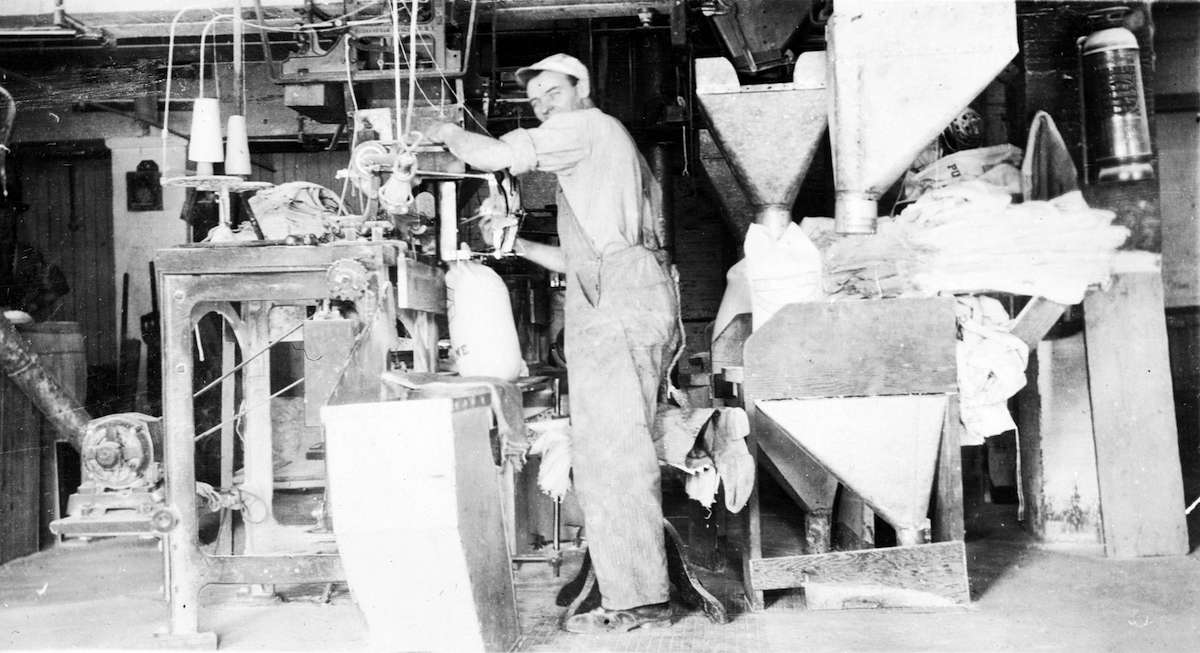

Conditions were especially tough for the roughly three dozen women who worked at the refinery, who spent 10-hour shifts on their feet sewing and filling bags of refined sugar.

By 1917, the 240-some workers at the refinery were organizing, planning to demand better pay and working conditions. Janet Mary Nicol, in an article for the BC History Journal, noted that B.T. Rogers got the news while aboard his yacht. Rogers was no fan of unions; in 1894 his father, also in the sugar business, had been killed by a brick flung by a striking worker at a refinery he owned in New Orleans. Rogers radioed a superintendent, instructing them to fire the worker who was leading the cause. The next day, workers walked off the job and formed a union.

The walkout led to a bitter 92-day strike. Rogers replaced workers on the picket lines with strikebreakers, whom he shuttled in via a car with curtained windows. He also hired the Thiel Detective Agency, which specialized in monitoring and spying on labour organizers and picket lines — the type of people many union activists describe as “Pinkertons.”

There were clashes on the picket line, but Rogers showed no sign of relenting. The workers ended up accepting defeat. About half of them were hired back: men received a six-cent-an-hour wage increase, while women received nothing, and all workers received a subsidized hot lunch from the employer.

A sweet business

While Rogers died in 1918, his immensely profitable business kept growing. His building is still one of very few large-scale sugar refineries in Canada, and by far the biggest in Western Canada.

The country’s sugar businesses, Belisle said, were tight-knit, and more than once were accused of price-fixing and co-ordination. Today, there are just two companies controlling virtually all sugar refining in Canada: Rogers Sugar and Redpath.

Labour dust-ups have also been a constant at the refinery. In 1975, workers walked out to demand meaningful wage hikes in the face of skyrocketing inflation. They eventually reached a deal including a 34.5 per cent wage increase. But the federal government’s anti-inflation board ended up capping the increase to a meagre 10.5 per cent. Workers ended up spending nine months on the picket lines.

And just last year, workers represented by Public and Private Workers of Canada Local 8 again walked off the job, this time in protest of proposed changes to work schedules to increase sugar production at the plant. This strike dragged on for four months until workers voted to ratify a deal in January.

The 2023 strike gave B.C.’s residents a taste of just how concentrated the sugar business is in Canada: the labour disruption led to empty shelves in grocery store baking aisles across the province.

Some parts of the building have changed over time. At one point, for example, it hosted a museum on the history of sugar in British Columbia and Canada.

“They actually used to bring kids in here, school groups, people who were taking baking courses, and they’d come in and get a tour about the whole history of sugar,” refinery employee Tom Cameron recalled during an earlier interview with The Tyee. There was once a cafeteria on the top floor, he said, where the entire workforce could eat for free.

Other parts of the refinery have changed relatively little since they were built, and more than one worker on the most recent picket line described an eerie, spooky atmosphere in the building.

That might be why it’s such a popular place for television shows. Episodes of The X-Files, Arrow and The Flash have all been filmed here.

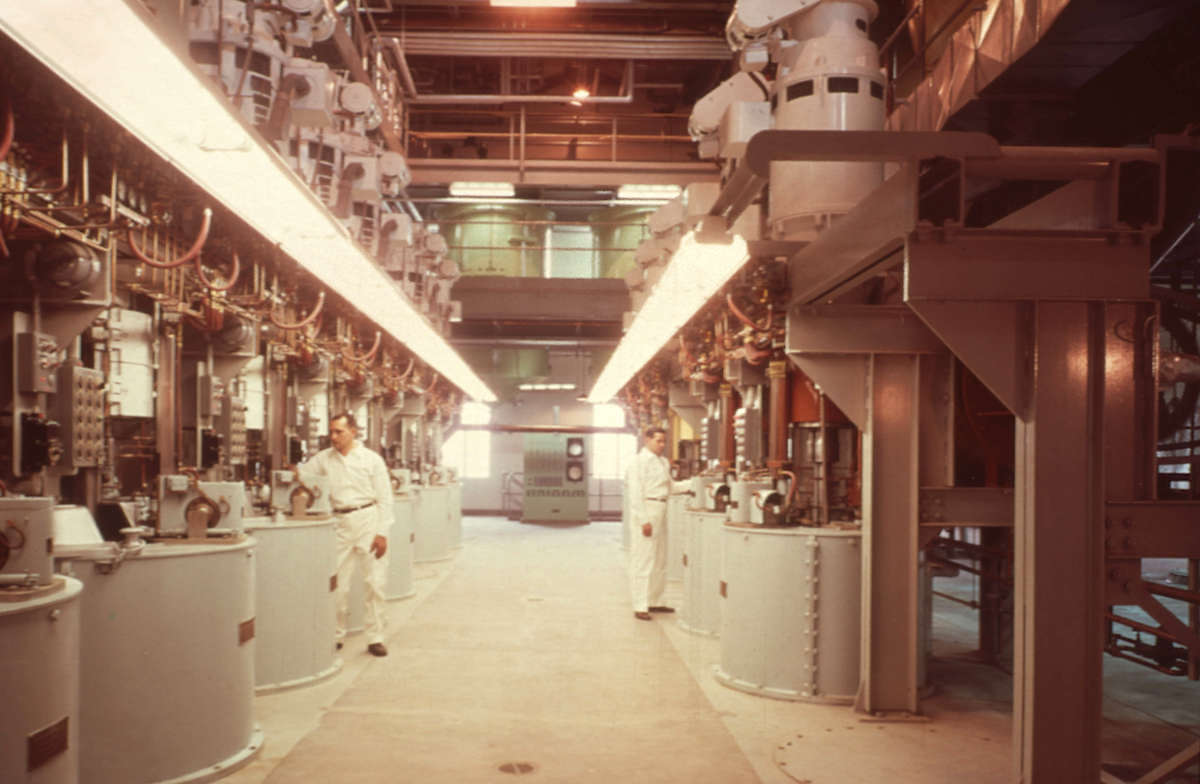

But in some ways, the refinery works in more or less the same way it has since 1892. Workers meet barges at Burrard Inlet, scooping massive quantities of raw sugar that makes its way into the old building for processing. Some becomes the white, crystalline product you put in your tea. Much of it is mixed with copious amounts of water to become a heavy, sweet mixture, which is then shipped off for further processing by giant manufacturers like Coca-Cola.

As in the late 19th century, it is still taking in sugar from overseas, still refining it down and still occupying the same spot on Vancouver’s waterfront, and in its history. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Labour + Industry

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: