The culture shock hits harder with every passing Christmas when I make the rounds for family dinners and am face to face with so much real estate.

We don’t host. None of us millennials do, not when our elders are the ones with actual land to their names. In our one-bedroom apartment, the Christmas tree is a condo-friendly thing purchased from Ikea to be displayed on a tabletop. But the real centrepiece of our living room is the winged drying rack that has made a permanent home there, ornamented with socks and underwear. There is barely enough elbow room for us, let alone a parade of extended relatives.

O little town of Vancouver, such is life in thee.

We arrive for dinner in pockets of the city and beyond, in Burnaby, Richmond and Surrey, where buses don’t come and towers don’t exist. The doors open and we look down foyers long enough to punt a football down. There are mud rooms and guest closets for storing our shoes and jackets; not a bed on which to throw one more item onto a growing mountain of outerwear. There are multiple washrooms; no need to line up. There are relatives staying in the guest rooms; no air mattresses or couches to crash on. There is stemware for specific wines and barware for something stronger; no plastic party cups in sight. I spot appliances like tall wine fridges and Dyson vacuums. Everything we have at home, from the electric kettle to the hand-held steamer, has to be bought in mini.

Christmas, fitting for a capitalist holiday, reminds me that houses exist. I visit more houses at Christmas than I do any time of year. For our generation, celebrations take place in so many apartments and their accompanying amenity rooms, with building regulations and strata bylaws telling us when the party’s over.

When it’s time to eat, we help ourselves to turkey on kitchen islands with enviable square footage of their own and dine in the light of full-sized Christmas trees.

We took space for granted when we were children because we thought it came with houses, and houses came with being adults. Now that we’ve grown up, the basics of our parents’ generation seem like luxuries to us.

As such dinners go, I end up making small talk with an uncle who asks about our living situation.

We own an apartment, I tell him, a fact that we’re quite proud of and privileged for as a young couple, especially not having to dip into the so-called Bank of Mom and Dad. (A story for another day, though I can tell you a career in journalism is not it.) We could do with more space in our one-bedroom, the bruises on my shins from running into furniture a testament to that, but at least this cube of air in the sky is ours.

The uncle is not impressed.

“Don’t you want a house?” he asks me.

In Vancouver proper, that would set us short a minimum of $2 million we do not have. But even if we could afford it, not really.

“At least, a townhouse?”

That’s still over $1 million.

These family dinners with the older generation tell only one side of the housing story. Christmas catch-ups with my peers reveal another.

Unreal estate

My scrolling on Instagram comes to a halt whenever I see an old acquaintance broadcasting their life in a brand new property for all to see. My fingers zoom into the screen and I pore over the pixels for glimpses of addresses and familiar streetscapes so I can Google the listings, dying to know the ludicrous sums they’re paying to stay in the city.

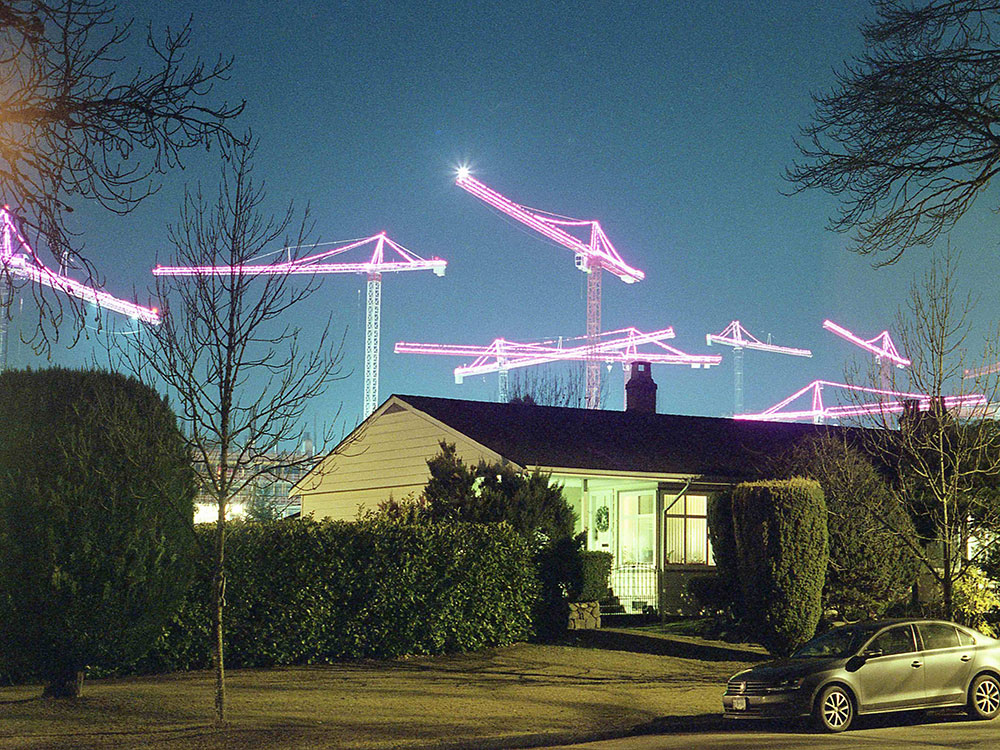

I confess: all the fervour about housing in Vancouver has made me obsessed. How can you not be when you’re surrounded at every turn by construction sites and for-sale signs with multimillion-dollar price tags?

Admittedly, these housing headaches are a world away from the more pressing plights of increasing homelessness and a rental market filled with hikes and displacement. But unaffordability is a rising tide, and those further up the housing ladder who own property are reshuffling their assets and debts in ways that are transforming family life.

There is a deluge of depressing data on how millennials and younger cohorts are increasingly shut out of home ownership, as well as the sheer privilege of those like me who’ve managed to get a foot in the door.

The boomer generation needed only five years of full-time work to save enough for a 20 per cent down payment on an average home in Canada. Today, that’s increased to 17 years, according to the non-profit Generation Squeeze.

It’s no surprise then that while 67 per cent of all Canadians own their homes, only 16 per cent of people born in the 1990s are homeowners, according to 2021 data from Statistics Canada.

Good for them, you might think. Sixteen per cent of 1990s kids must be earning enough money to afford a home.

But that number hides something: the supports that prop them up to reach this milestone.

‘Out of the land we came and into it we must go’

When Vancouver’s housing market became superheated in the 2010s, many of my childhood friends in their 20s were buying condos.

Yes, parental help was involved. But the Bank of Mom and Dad, like any other bank, has a wide variety of financial arrangements and products.

Some parents bought together with their children as co-owners. Some gifted the down payments or offered the forgivable loans that allowed their children to become the sole owners, leaving them to handle the monthly costs thereon. While there were children who moved in right away, others rented out their new units, collecting a profit while living at their parents’ home rent-free.

The average family in our neighbourhood of Oakridge made less money than the average Vancouver family. So what happened that allowed my peers and their parents to buy properties?

There are neighbourhoods like ours across the region, home to immigrants from all over with very different ideas of what family and property mean beyond the nuclear norm.

One of the books we read in high school spoke to those sentiments. In The Good Earth, one of the characters says, “It is the end of a family — when they begin to sell their land.... Out of the land we came and into it we must go — and if you will hold your land you can live — no one can rob you of land.”

To many immigrant Vancouverites, property means more than just profit. Property means security. Property means citizenship and inclusion. The parent of one friend was convinced that owning a house was proof that racial discrimination was at an end. Real estate is real, and its absolute tangibility cannot be argued with.

A sprinkling of news reports of immigrant students and homemakers buying houses with money earned overseas hides the massive mortgages shouldered by families who buy houses at any cost necessary, from living with extended relatives under one roof to paying larger chunks of their incomes.

A 2017 University of British Columbia study showed how a staggering percentage of certain diasporas pay more for housing than their white counterparts and has resulted in high levels of home ownership. In Metro Vancouver, 44 per cent of white people own property compared with 54 per cent of people of colour, with Chinese Canadians — the largest diasporic group — topping out at 74 per cent. As long as you’ve got the money, you too are welcome to participate in the colonial ownership of unceded Indigenous territories, whatever your race.

The first thing many of our neighbours did after paying off their mortgage? They bought another house nearby.

I can still point out which houses are the second and even third investment properties of the families in the neighbourhood, playing a game of Monopoly on their own blocks. There are white-collar and blue-collar workers among them, from public servants to home repair. These days, houses cost too much. Instead, families are buying nearby condos for personal investment and for their children.

For every adult who thinks that parenting means letting their child fend for themselves, there is another who thinks that helping their child out with housing is a no-brainer when they’ve been blessed with so much.

The Bank of Mom and Dad does not consider these handouts. Like any other bank, they have an interest too. Parents are investing in grandchildren, speeding up the process and keeping their children, who will one day take care of them in some way or another, close by.

The two-bedroom problem

I am 31, and catching up with my peers over Christmas is now filled with announcements and gossip around engagements, breakups and, of course, pregnancies.

Buying a one-bedroom apartment as a first home is no small feat. But it doesn’t make jumping from that to a two-bedroom any easier. Whether a condo apartment or a townhouse, it’s a difference of a few hundred thousand. It’s this second bedroom that puts the Bank of Mom and Dad to the test.

For those families with enough capital to afford a larger home, great. But the others?

Some adult children, now expecting, are moving in with their parents and even grandparents, a growing Canadian demographic. Some families have added laneways or rebuilt their houses larger in anticipation of this life stage, with the adult children moving into the new unit or the grandparents downsizing to free up the roomier quarters for their grandchildren to be raised in. The condos previously occupied by the adult children are held on to as investment properties and rented out.

Home ownership used to be a key marker of an independent adulthood. With such an array of arrangements, no wonder millennials have verbed it into “adulting,” a journey that never seems to arrive at a destination because it doesn’t look like what it used to.

Hearing the details of some peers’ family portfolios of properties is dizzying, as if they’ve become feudal lords. Also dizzying is the navigation around privacy and expectations. Some families are able to stake out their personal boundaries just fine. Others struggle, from daily matters like unwelcome visits to lifelong issues like a constant sense of indebtedness. The offer of “free” housing can be uncomfortable, especially for those marrying into families with property, knowing the roof and the walls are owned by their in-laws. It can also mean more exposure to the older generation’s heteronormative ideas about family life: when to marry, when to have kids, if at all. Is this “adulting”?

It’s a lot to think about, yet many feel it without thinking about it at all. To them, that’s just what family is. In these communal households, life and assets are always shared, a mix of joy and struggle, convenience and burden.

Owning one’s land is so important that many of my local friends have never rented, living with their parents until marriage. It’s a mix of cultural reasons, conservative family values and a thrifty immigrant mindset, resulting in a mentality that looks upon renting as the most idiotic thing in the world.

Years ago when my partner and I first set out to do such a thing, we used the Chinese classifieds. At one showing, the landlord eyed us with extreme suspicion.

“Why are you renting and not buying a condo?” she asked. “You’re not students and your parents live here.”

We were rejected immediately. Ownership, to some, is the only thing that makes sense.

‘The city of my choice’

Is it time to break up with Vancouver?

This was the thesis of a number of popular essays published in the late 2010s, authored by young professionals who ditched pricey Vancouver for new frontiers, whether the suburbs or another city entirely.

The stuff they liked about Vancouver? “An organic grocery, a Latin restaurant that served killer tacos and fresh-squeezed margaritas, and a pub with a great quiz night,” according to one Vancouver Magazine essay. Living in “an affordable up-and-coming area that was still rough around the edges... the abundant street culture, the cool coffee shops, cheap sushi places and Asian produce markets that sold foods I wasn’t totally familiar with,” read another in The Tyee.

As these departees browsed the catalogue of Canadian destinations like Calgary with calmer housing markets, they discovered it’s not so bad after all. “You can find bike lanes and pedestrian-friendly neighbourhoods and hip cafés almost anywhere now,” one writes.

But there’s an unexamined underpinning in these essays, according to Canadian sociologist Zachary Hyde in an analysis for the Mainlander: “I, a hard-working, usually white, middle-class person, did everything right, became successful, and yet am still unable to afford to live in the city of my choice.”

As Hyde argues, there’s an economic individualism at work in these narratives. They turn a “gentrifier’s gaze” to what affordable communities have to offer without thinking of the impacts. The Edmontons and Ottawas of Canada will, in turn, go the way of Vancouver.

When former Vancouverites published their breakup letters, I thought about all the people I knew who could not break up with the city, no matter how unaffordable.

To some, cities are products; to others, they’re a lifeline.

Members of families with elders wouldn’t dream of leaving aging seniors or parents who don’t speak English, not even for a city 30 minutes away. For newcomer singles, Vancouver is uniquely multicultural, with robust diaspora communities that offer social supports and economic opportunities.

Mobility is a privilege afforded to those without dependents, whether they be elders or family thousands of miles away who depend on a paycheque.

Those who stay here are simply willing to pay a lot more.

Home ownership as a human right

Families pooling their assets is a personal means of survival, riding the waves of a rising market to stay afloat. But this does nothing to address the societal unaffordability that Vancouver has on its hands as governments are slow to provide housing options or rein in a real estate market that continues to reward speculation.

An analysis of 2021 data by Statistics Canada found that ’90s kids with parents who own a single property were twice as likely to become homeowners than their peers with renter parents. And if the homeowner parents had more than one property, those ’90s kids were three times as likely to become homeowners.

You probably didn’t need this report to come to the conclusion that it helps to be born in a family that owns property. And that the later you were born, the more unlikely it is that you ever will. It’s not fun to be left out. Both my local friends without access to parental capital and those who've moved to Vancouver are often triggered to learn about the housing help within feudal families when they're working so hard on their own to be able to make it in the city.

Whatever your housing situation, it’s important to pay attention to where we are headed. Because whether the Canadian dream of home ownership is attainable or not, it’s the dream that is still aggressively being sold.

The Liberal government has joined other jurisdictions in calling housing a human right, but many seem to have interpreted this to mean that owning a home is a human right.

Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland once called the inability of young people to afford a home an “intergenerational injustice.”

For decades, provincial and federal governments have offered little relief to renters compared with the amount of policy that privileges home ownership, from tax breaks to a parade of programs for first-time buyers. There was the B.C. Home Owner Mortgage and Equity Partnership in 2016, the federal First-Time Home Buyer Incentive in 2019 and last year’s First Home Savings Account.

Who can buy into this fantasy of real estate? In his seminal work Capital in the Twenty-First Century, the economist Thomas Piketty says we are returning to an age of “patrimonial capitalism,” a hierarchy based on inheritance. Though one difference of our current climate is how the middle classes who have acquired property are allowed to cruise on upward.

It’s no wonder that those who can afford it have clung on to home ownership as security, because everything else has been made precarious.

What we talk about when we talk about housing

If you have too much housing, you’re elitist. If you have too little, you’re failing. If you relied on someone for help, you’re spoiled.

They say you should never talk about politics and religion at the dinner table, and I wonder if housing in Vancouver should be added to the list to save guests from uncomfortable conversations about privilege and wealth at Christmas parties.

I do wish we could talk about housing honestly. But it’s hard to take housing advice from elders when they’re sitting on huge houses with multicar garages that they bought for so much less. It’s hard to listen to their defences of having toiled to earn their properties because it’s true, albeit in a very different financial landscape.

As households reorganize to survive the times, who’s to say what’s the right way to live? As the old markers of a middle-class life never materialize, the concept of “adulting” becomes more elusive. The problem is when those with privilege aren’t able to see that there is something wrong with the system because they’ve profited handsomely from it, and offer advice about surviving the market that ultimately excuses runaway capitalism to keep doing its thing.

I remember a family visit to a relative’s 8,000-square-foot house. My grandfather, impressed, had a few words for me and my young cousins.

“If you work hard, one day you’ll have a house like this too.” ![]()

Read more: Housing

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: