- A City on Mars

- Penguin Press (2023)

Much of the science fiction I absorbed as a boy in the 1940s and ’50s was dedicated to the problems of establishing and sustaining human settlements on other planets, or in space itself. These problems usually involved dealing with the aliens, fighting with the aliens or fighting with other human groups.

In other words, the science fiction I read was a rehash of the European conquests since 1492, which taught Europeans that expansion and exploration would lead to untold wealth and power. Travel to other worlds was just an extension of European imperialism, which would culminate in something like the Galactic Empire that American author Isaac Asimov envisioned in some of his 1950s novels.

That’s fine as the basis for predictable space operas like the movie Rebel Moon and the TV series The Expanse, but actually settling the moon or planets like Mars would require knowledge and resources we don’t have.

Enter Kelly and Zach Weinersmith, an American married couple who write popular science books together. They are part of a community that seriously wants colonies in space, and eventually whole new nations on other planets. Unlike some members of their community, the Weinersmiths are willing to think through the hazards — biological, psychological, legal and political — facing space pioneers. But even they ignore some genuine showstoppers likely to keep future space pioneers on the launching pad.

In their 2023 book A City on Mars, the authors point out that space flight enthusiasts like Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk may tout space colonies as a kind of insurance: if anything terrible happens to Earth like climate catastrophe or a nuclear war, humanity will survive elsewhere in the solar system. (I heard the same thing from Ray Bradbury circa 1958.)

By this logic, should we go to Mars to survive global heating? “Leaving a 2 C warmer Earth,” the Weinersmiths observe, “would be like leaving a messy room so you can live in a toxic waste dump.”

As for escaping war, the authors point out that a community in space could easily have the technology to drop an asteroid anywhere it wanted to — including on other settlements or the Earth itself.

Of course, any space community would first have to somehow overcome very serious physical and biological obstacles. The Weinersmiths note that in the 63 years since Yuri Gagarin orbited the Earth in the first human journey into space in 1961, only a few hundred people, most of them men and all of them highly trained and physically fit, have gone into space.

Most have stayed in low Earth orbit, protected by the Earth’s magnetic field from serious exposure to radiation. No one has stayed in space more than 437 days.

Emigrants to the moon or Mars would be exposed to far more radiation, both in transit and on the surface. (Neither the moon nor Mars has any magnetic field to speak of.) Migrants to Mars would take at least six months to reach it; their time in free fall would weaken their bones and muscles — even if they exercised daily. They might be physically unable to work until they’d adjusted to the one-sixth gravity of the moon or the one-third gravity of Mars.

Fighting for breath

Settlements would have to be underground, in lava tunnels, to shield against more radiation. There is very likely water on Mars, and in craters at the moon’s south pole that have never been exposed to sunlight. But extracting and purifying it, in either place, would be slow and hard. No water, no settlement — or even oxygen, which would come from electrolyzed water.

And as the Weinersmiths point out, we have no idea if migrants could become pregnant in low-gravity environments, or safely give birth. We don’t know if babies could thrive and grow, or become stunted, with brittle bones and feeble hearts. No healthy babies, no permanent settlement.

The Weinersmiths make a solid case against the viability of lunar and Martian settlements, not to mention space habitats. But they are actually pro-settlement, and willing to think that technology might overcome these obstacles. They look beyond settlement to other issues, like space law.

Dibs on the moon

If China builds a base at the moon’s south pole, can it legally claim the whole moon? Or just the southern hemisphere? Or just the ice-rich dark craters? Does India have first dibs because its Chandrayaan-3 lander reached the south pole first, in August 2023?

We already have an Outer Space Treaty, signed in 1967, which offers a framework for sharing resources and doing scientific research in space, much like in Antarctica. But it would need serious renegotiation if countries decided to build permanent bases.

The Weinersmiths do a good job of working out the details and implications of the laws needed to govern settlements in space — which would presumably exist because of the discovery of valuable resources on the moon, Mars or some solid-gold asteroid. But it’s hard to imagine what resources would be worth fetching from Mars or the asteroid belt, and a solid-gold asteroid would of course make gold worthless.

The authors also try to work out the conditions under which a lunar or Martian settlement could become a self-governing nation in its own right. This is another old trope in science fiction: the rebel colonists seeking freedom from oppressive Earth regulation. And of course it’s just the American Revolution again, with blasters instead of muskets.

But the authors make a persuasive point: if you want to settle space, don’t hurry. A viable settlement on Mars would require thousands of genetically diverse people with thousands of skills. The Weinersmiths argue that space settlement should “wait and go big” — work out all the technological and biological problems, pass the laws and then haul a million settlers to their new home within a few years. That is, if you can find a million people who seriously want to live in tunnels and drink desalinated Martian water.

The Weinersmiths’ lively, often funny style makes this a very readable book. But their whole argument assumes that 21st-century technology will continue to grow in a 20th-century environment where climate change is just a wild theory. Rocket launches are environmentally damaging, producing carbon dioxide emissions, and according to the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, they currently inject about 1,000 tons of soot into the upper atmosphere every year. More launches would create more CO2 and more soot.

All politics are domestic

It will be an impressive feat to keep building and launching rockets as storms and floods sweep the planet. Most taxpayers would likely prefer money for space communities to be spent on climate-proofing communities right here on Earth.

The Weinersmiths are right to argue for large communities in space, but they say very little about the politics of such communities. Perhaps a libertarian like Musk might want fellow libertarians to settle on the moon or Mars, but they would have precious little liberty once there.

Food and water would be rigidly rationed, as would energy. Living conditions would be squalid, a routine of hard work and exhausted sleep, interrupted by frequent medical and psychological checkups. Only cases of physical and mental illness would get special treatment, if such treatment were available. Otherwise, any inequalities would lead eventually to the community’s breakdown.

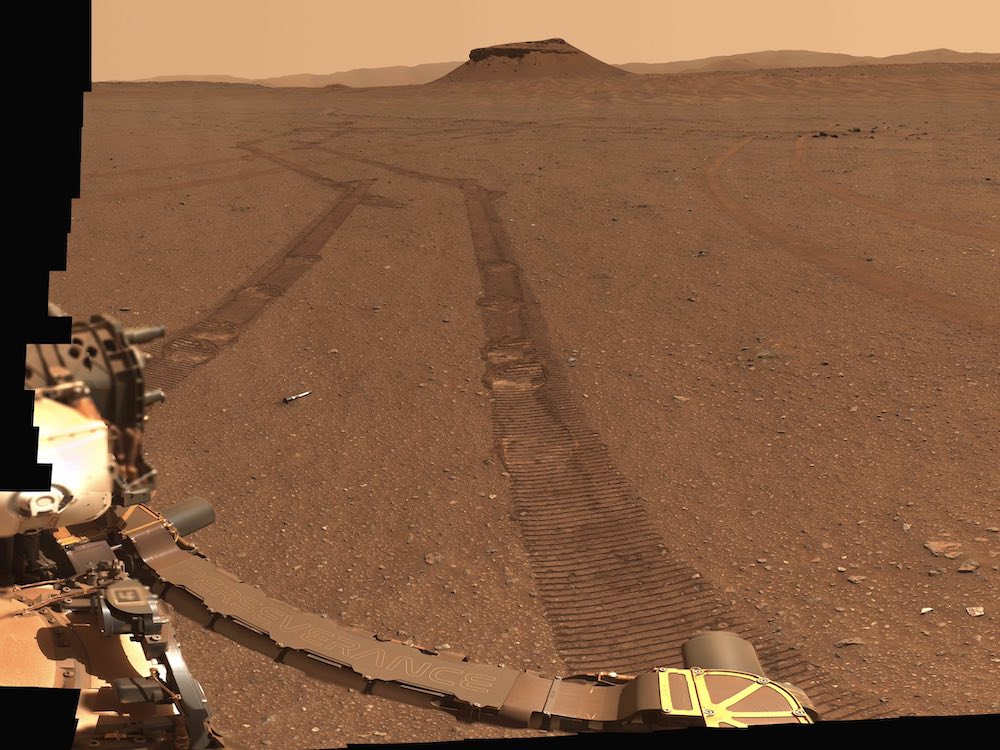

Certainly we should continue to explore space and the planets. But we should send “astrobots,” not astronauts, like the rovers we’ve sent to Mars and the moon. We have already learned a great deal from such probes, and we will learn much more, at a fraction of the cost of sending humans. Future probes using artificial intelligence would likely learn more about other worlds than even the most talented scientist-astronauts could.

And if we really wanted to know what it’s like to roll across the Sea of Tranquility or soar over Valles Marineris, astrobots could give us virtual reality tours, right here at home. They would be far more exciting than any space opera. ![]()

Read more: Books, Science + Tech

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: