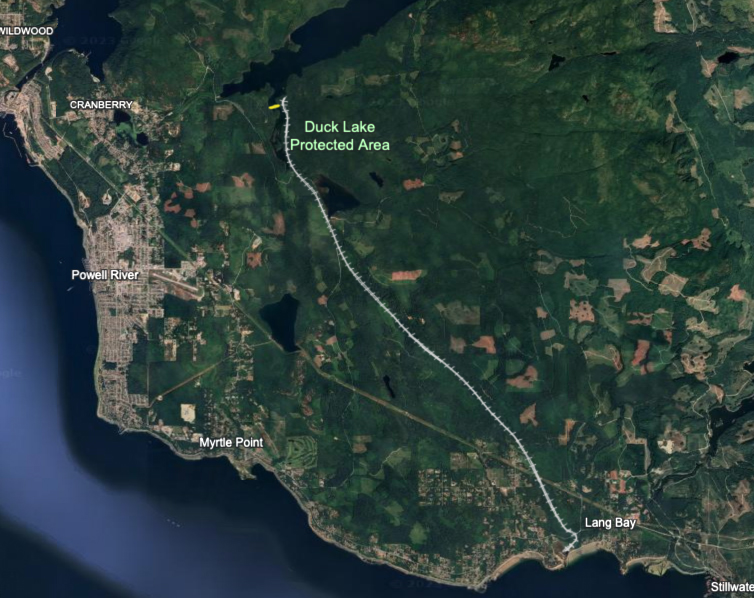

A few summers ago, my friend Nola took me paddle boarding at Haslam Lake, in one of the more accessible recreational forest areas surrounding what is currently known as Powell River, B.C.

We drove down a logging road a little way east of Cranberry Lake, hopped over a concrete barrier and lugged our boards to the lake, which is known as θaʔyɛɬ (pronounced “Thah yetl”) in ʔayʔaǰuθəm, the language of the Tla’amin, Klahoose and Homalco peoples, who have lived on these lands for at least 10,000 years. θaʔyɛɬ means “freshwater lake.”

And this one is particularly gorgeous, stretching about 12 kilometres tip to tip, ringed with second-growth trees, calm and quiet — it’s not open to motorized boats.

We paddled towards the marshy area where Haslam begins to run into Duck Lake. We glided over logs and detritus, such as a wooden wire spool, that we could see perfectly in the clear, glassy water.

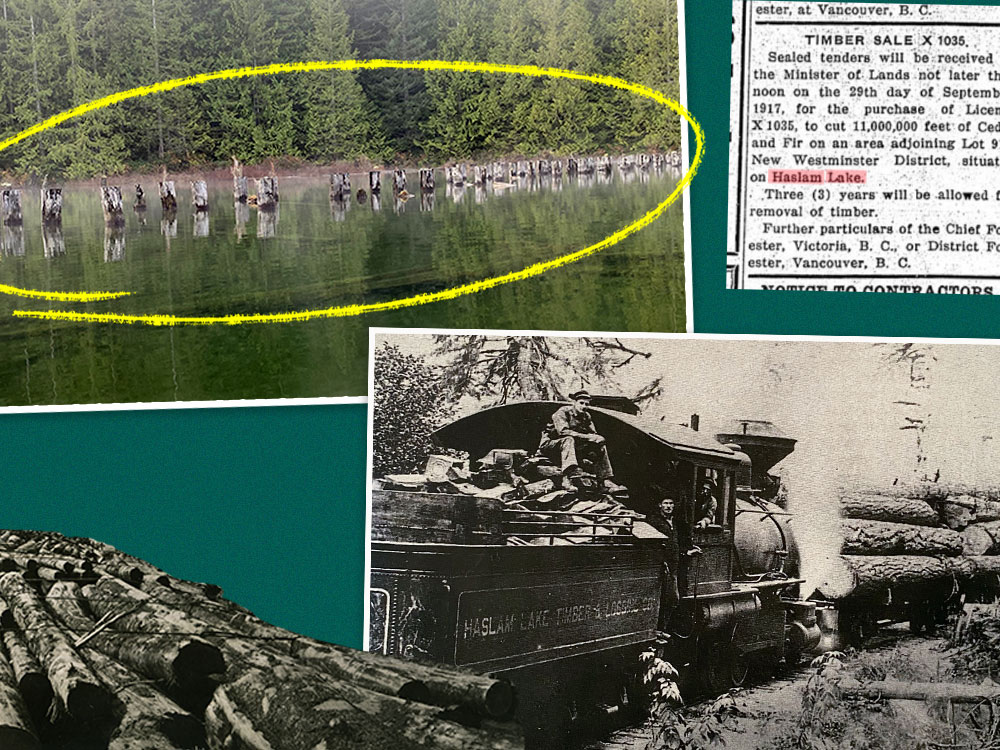

And we came across a relic of human activity much more recent than Tla’amin history in the area, but nonetheless haunting: a series of evenly spaced, cylindrical wooden poles jutting out of the clear, calm water.

Do you know what they are?

Today, Haslam Lake is the main source of drinking water for Powell River.

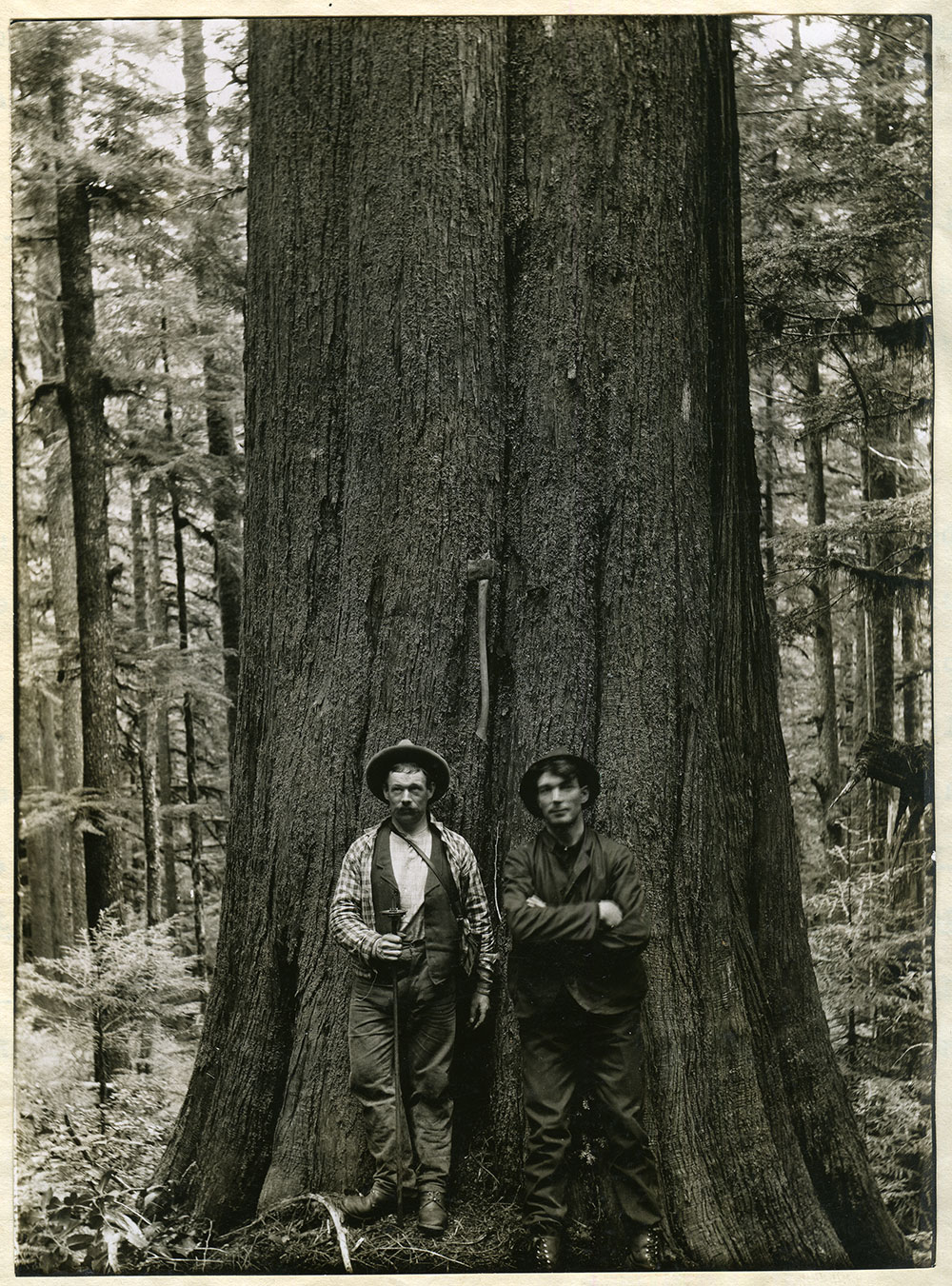

Over a century ago, however, the watershed was one of the area’s busiest logging spots.

Those cylindrical wooden poles? They’re old piles that supported a train trestle bridge that spanned this area of Haslam Lake.

Rather than connecting two populous areas — the function I generally conceive of for railways — this one, and many others like it, connected the forest to a log dump at tidewater.

Records from the time show that licences around Haslam Lake provided for the logging of fir and cedar — Douglas fir, balsam fir and western red cedar.

When I returned in late November to take a closer look at the piles with another friend, cabinetmaker Gillian Dyck, she paddled up and inspected a large splinter: the bridge’s piles were constructed from western red cedar.

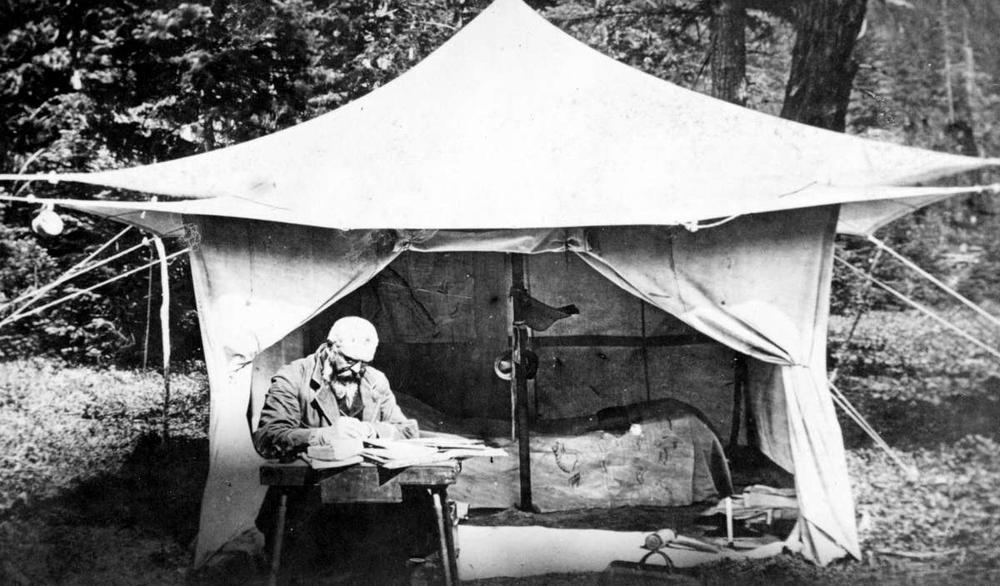

The next part of the mystery is solved by poring over books at the qathet Museum and Archives, and looking at the websites of the Powell River Forestry Heritage Society and a local blog about the area’s vanishing settler history.

It appears that the rail line running to this general area was initially constructed by Haslam Lake Timber and Logging Co. in 1913-14, and extended by Straits Lumber Co. around 1916. It ran along Lang Creek to Lang Bay, at tidewater, where there was a log dump.

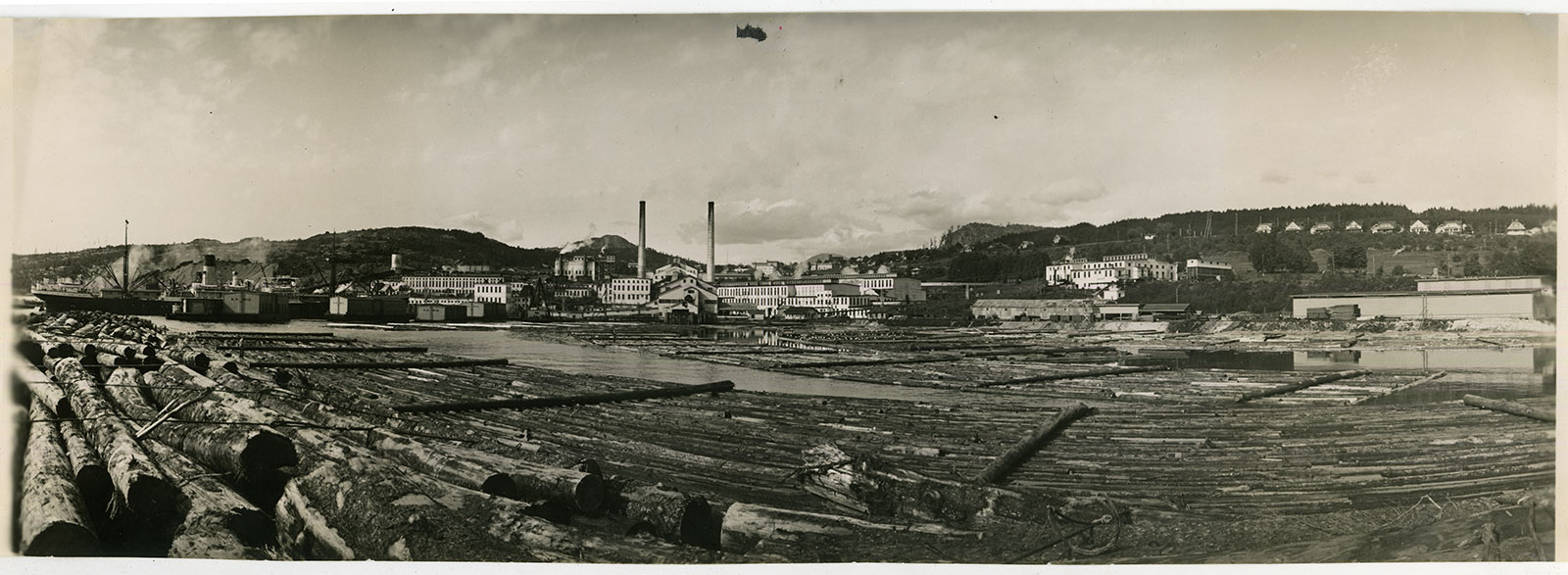

From what I can piece together, the fir and cedar would have been harvested in the Haslam Lake watershed, temporarily stored in Haslam Lake and then hauled down to Lang Bay to await transport via water to a mill.

Soon, the line was taken over by Bloedel, Stewart and Welch — a predecessor company to MacMillan Bloedel, the forestry giant acquired by Weyerhaeuser in 1999. Bloedel, Stewart and Welch tied the upper part of the line into a pre-existing line of theirs that ran to the ocean at Myrtle Rocks, north of Lang Bay.

A 1931 forestry survey done for the government by M.W. Gormely notes: “Main line of the Bloedel, Stuart and Welch Logging Co.: runs north from Myrtle Point to Duck Lake; thence east deep into Lot 913. A spur goes north to Haslam Lake. All grades are in good condition.”

Then: “Entire system abandoned.”

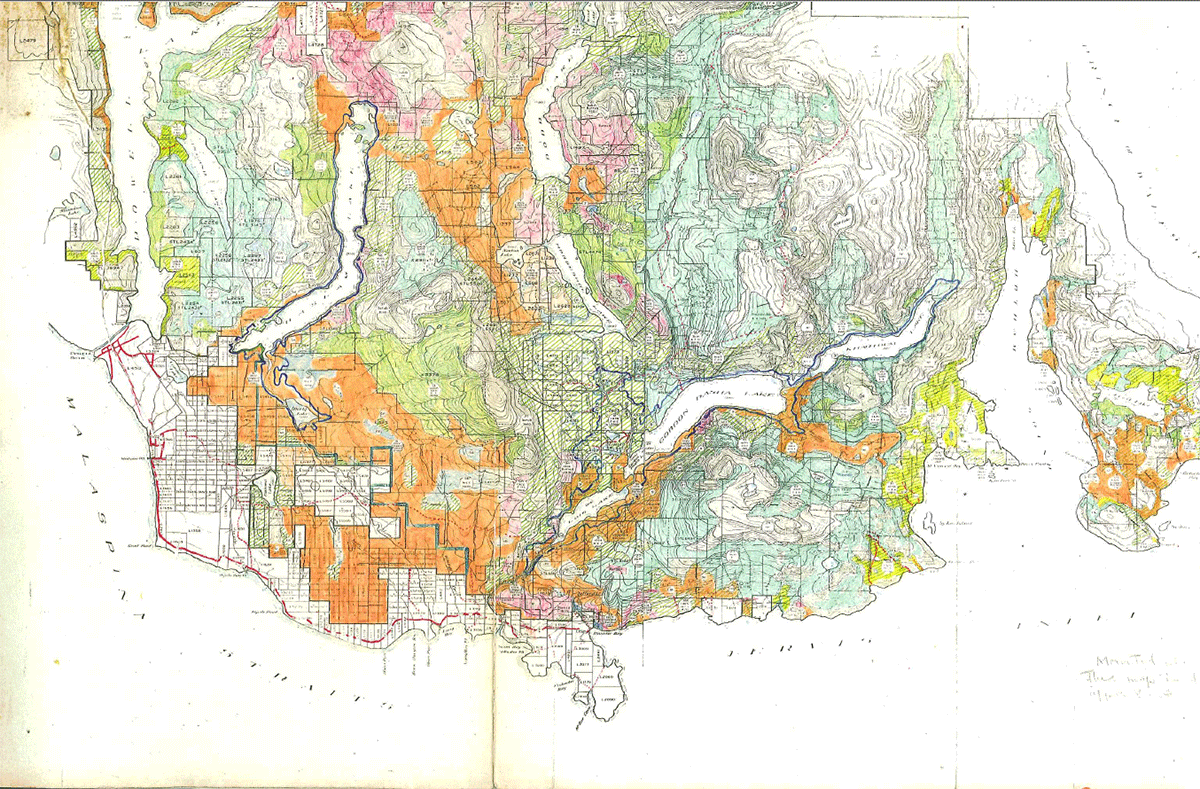

The map put together for Gormely’s forestry survey shows why: the usable timber had more or less all been harvested. Or burned in wildfires.

In 1906, there were 26 logging railways operating in B.C.

By 1924, that number had climbed to 76. Forty-one of those were located on Vancouver Island, 12 in the Kootenays, 17 in coastal mainland areas such as Powell River and one on Haida Gwaii.

In the qathet region alone, there was the Paradise Valley railway, four railways running alongside Lang Creek (one of which was the Haslam Lake Timber and Logging Co. line), one in Theodosia Inlet, another in Stillwater, one in Wildwood, one in Jervis Inlet and one connecting what is currently known as Willingdon Beach to the newsprint mill in tis’kwat, which is also known by the self-descriptive name Townsite.

“Most were built as temporary systems designed to last only as long as the local timber supply,” Robert D. Turner wrote of logging railways in an overview article for the journal Material Culture Review in 1981.

When the timber was gone, the railways went, too. And soon, they were also no longer the most efficient way to log an area.

By the mid-1950s, Turner wrote, most of B.C.’s logging railways had been replaced by trucking systems, using logging roads (some of which did use converted railway grades).

By 1964, only three logging railways remained in the province, all on Vancouver Island.

Tla’amin, Klahoose and Homalco First Nations excluded and dispossessed

A few decades before the Haslam railway was constructed, the provincial government essentially stole timber harvesting land out from under the Tla’amin people, effectively excluding them from forestry activity in the areas that were easily reachable from tis’kwat.

“The British Columbian government... ripped a sizable chunk from the Tla’amin’s land base with the survey of Lot 450 for timber baron R.P. Rithet” in 1873, professor Colin Osmond, then a PhD student at the University of Saskatchewan, wrote in a 2018 Tla’amin Nation newsletter.

The following year, in 1874, Tla’amin leadership “petitioned the provincial government to protect their lands from settlement through surveys.”

But the conflict only heated up; the provincial government was unresponsive, and settlers began encroaching closer and closer to Tla’amin villages, leading Tla’amin people to seize timber directly from them.

Via email, the Tla’amin Nation pointed to some correspondence from Indian Commissioner Gilbert Malcolm Sproat to provincial superintendent of Indian Affairs Israel Powell that reveal what took place next.

In February 1879, Sproat wrote to Powell to “beg” him not to permit out any land on Harwood, Savary or Hernando islands until Sproat had finished his work with the Tla’amin, Klahoose and Homalco First Nations in the area.

Later that year, at the end of August, Sproat made a trip up the coast, again writing to Powell.

“Their great wish was to have a piece of timber land from which they could sell sawlogs — they are able to follow the industry of ‘hand-logging.’ The village was built where it is, partly in the view of their getting a share of the only good timber land near it,” he wrote.

“Last year the present [government], without mentioning their intention to the [commissioners], sold several thousand acres including all the good timber land, and coming close up to the village.”

Tla’amin, Klahoose and Homalco people were concerned that not only would they be shut out of timber land, but they’d also lose the land they used to cultivate crops.

Sproat wrote that he communicated with another government official to ask him to refuse any further presumptions or purchases of land without first communicating with Sproat. But the official brushed him off.

“In Sproat’s estimation,” Osmond wrote, “the government stalled on their efforts to survey the Tla’amin’s reserves (among others in the area) due to the large quantity of valuable timber in the region, the discovery of deposits of iron ore, copper and gold on Texada Island, and rumours that the soon-to-be-built Canadian Pacific Railway might locate its terminus in Bute Inlet.”

Missing from the map

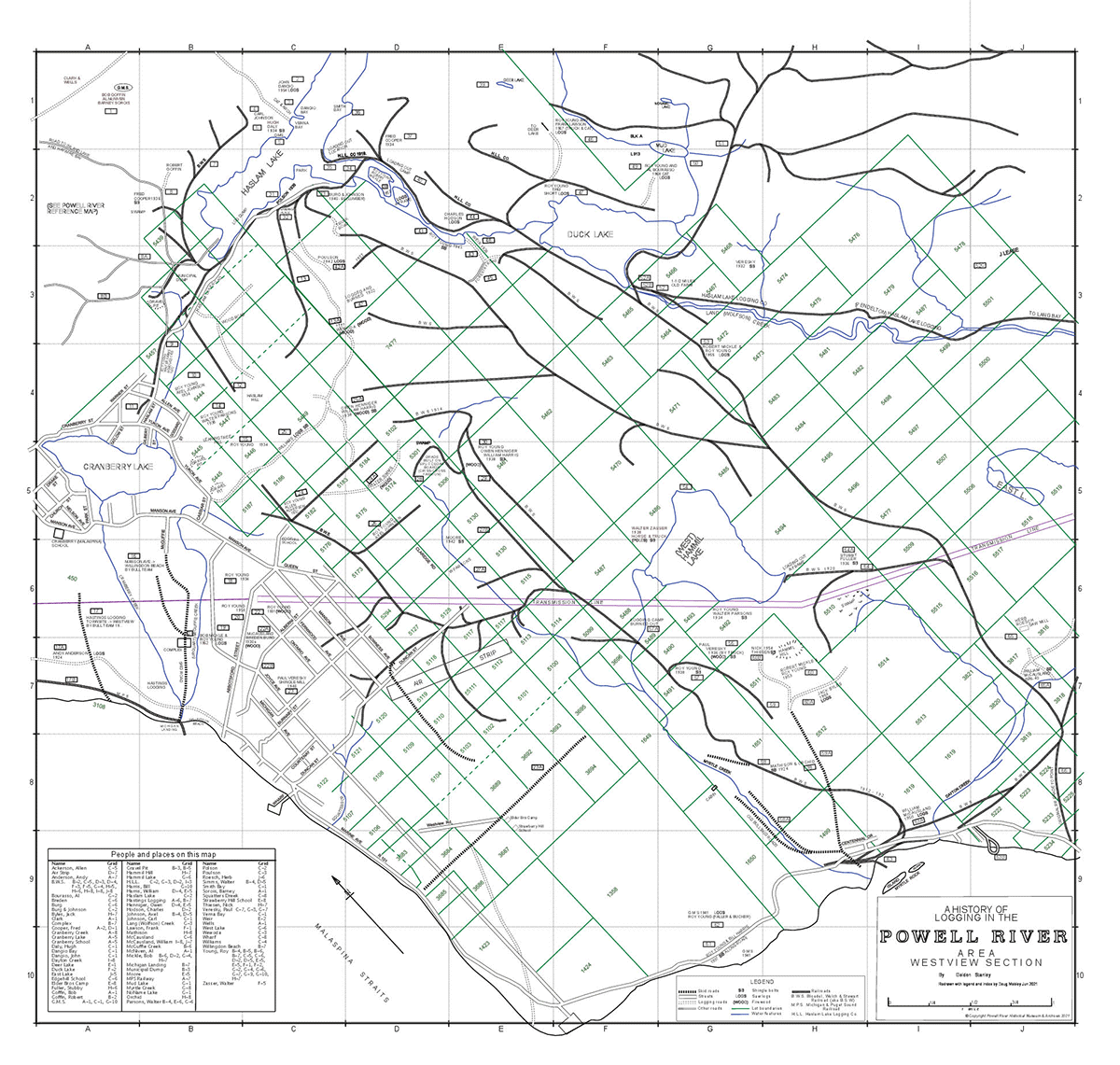

As I consulted and reconsulted the maps I’d found of the Haslam Lake Timber and Logging Co. railway, one mystery remained. None of the maps showed a trestle running east-west across the lake, where my friends and I had gone paddle boarding.

The maps I’d been looking at showed the northern terminus of the Haslam Lake Timber and Logging Co. main line skirting the eastern side of Haslam Lake, running more or less north-south — the silver railway I’ve drawn on the map below. But the old trestle piles cross the lake itself, running east-west — the yellow bar on the map below.

The answer to this final remaining mystery was provided by Dave Florence, president of the Powell River Forestry Heritage Society. He sent me a map created by Golden Stanley in the early 1980s and updated by a qathet museum volunteer in 2021 that shows a far more complicated spiderweb of rail lines in this section of Powell River.

This map includes the east-west line that we can see the remnants of in the lake today. In Stanley’s version, the trestle connects the main line to three spur lines south of Haslam Lake.

“The important thing to note in looking at our railway maps is that the spurs were not in place at the same time,” Florence tells me over email.

“One would be built, and when the logging was done, the ties and rails were collected up for the next spur. So when Stanley and others walked the ground and sketched their maps from the 50-year-old grades and pilings they observed, it would be easy to mistake a spur for the main line.”

An old photo from the Powell River News, reproduced in Powell River's Railway Era by Ken Bradley and Karen Southern, shows what it says is a 2-6-0 locomotive lumbering down the grade towards Lang Bay in 1911 — a little earlier than the existence of the northern extension of the line to Haslam Lake.

Reckoning with the past

Even though the infrastructure was never actually meant to last, if you know where to look, the evidence of early settler logging and the railways that sustained it is everywhere.

In Haslam Lake, the ghost of the railway remains preserved in its waters over a century later — in part due to the preservative properties of water, and because cedar is very rot resistant.

After the Willingdon Beach railway was decommissioned in 1926, it became a walking and cycling trail connecting the Westview neighbourhood to tis’kwat, or Townsite.

The Willingdon Beach trail is home to key Tla’amin cultural heritage — shell middens, culturally modified trees and an old intertidal fish trap — as well as Tla’amin burial sites.

It also includes logging artifacts.

These glimpses of logging railways offer a chance to reflect on the area’s past — and its future.

Logging, like all resource extraction in B.C., is inextricably linked to early colonial government policies like the creation of the reserve system and the establishment of “Crown land,” on which 95 per cent of timber harvesting still happens today.

It was this colonial view of the land that led to the timber being extracted as quickly and efficiently as possible, without much thought for ecosystem health or how the region had sustained Tla’amin people for thousands of years — not to mention the dispossession of the nation, and their exclusion from timber harvesting.

It’s this world view, too, that led to policies of assimilation of Indigenous people, residential schooling and segregation in company towns like Powell River, where Elders say they were only allowed to come to town on business, and had to sit in a separate part of the Patricia Theatre if they wanted to see a movie.

So what does it mean to reckon with this history? And what could reconciliation look like?

The Tla’amin Nation has asked the municipality to change its name in recognition of the deleterious effects Israel Powell had during his time as superintendent of Indian Affairs.

The regional district ditched “Powell” in 2017 and renamed itself the qathet Regional District — a name meaning “working together” that was gifted by the Tla’amin Nation.

As I researched the ghost trestle, relying on sources that draw from colonial government documentation and settler oral histories that draw pride from reflecting on hardscrabble pioneer lives, I wondered how the keepers of this history were thinking through these questions.

Florence, the Powell River Forestry Heritage Society president, sent me a document he shared with the Powell River renaming committee. While recognizing colonial harm and supporting other moves towards reconciliation, including the renaming of individual places in the area that have Tla’amin names, Florence does not believe the city should change its name.

“From the Papal Bull ‘Inter Caetera’ issued in 1493 through to all of the Canadian assimilation policies, we as a settler society have much to apologize for,” Florence writes, in part. But the solution does not include “demonizing” Israel Powell, he writes, which may have the opposite intended effect of letting settlers and the descendants of pioneers off the hook for the roles we played in this history.

Local group the Name Matters, comprising Indigenous and non-Indigenous volunteers, makes a different case. They say the name change corrects the colonial imposition of the city’s current name and its attempted erasure of Tla’amin place names.

Meanwhile, five or six kilometres west of Haslam Lake and within the boundaries of Lot 450, at the terminus of the Willingdon Beach rail trail, at least one colonial dispossession is about to be righted.

The mill, which was built in 1910, effected the ouster of Tla’amin people from tis’kwat and led to the establishment of Townsite as a company town, has been permanently curtailed since August.

In late October, seven generations after the area was taken from Tla’amin people, the nation signed a memorandum of understanding with the province to reclaim the site.

Tla’amin leadership, over 100 members of Tla’amin’s drum family, as well as the oldest and youngest members of the nation, joined Premier David Eby, MLA Nicholas Simons and Minister of Indigenous Relations and Reconciliation Murray Rankin for the signing of the MOU.

“For seven generations our story, our history, our connection to this place hasn’t changed,” Hegus John Hackett told the crowd. “What has changed is the listener.” ![]()

Read more: Transportation

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: