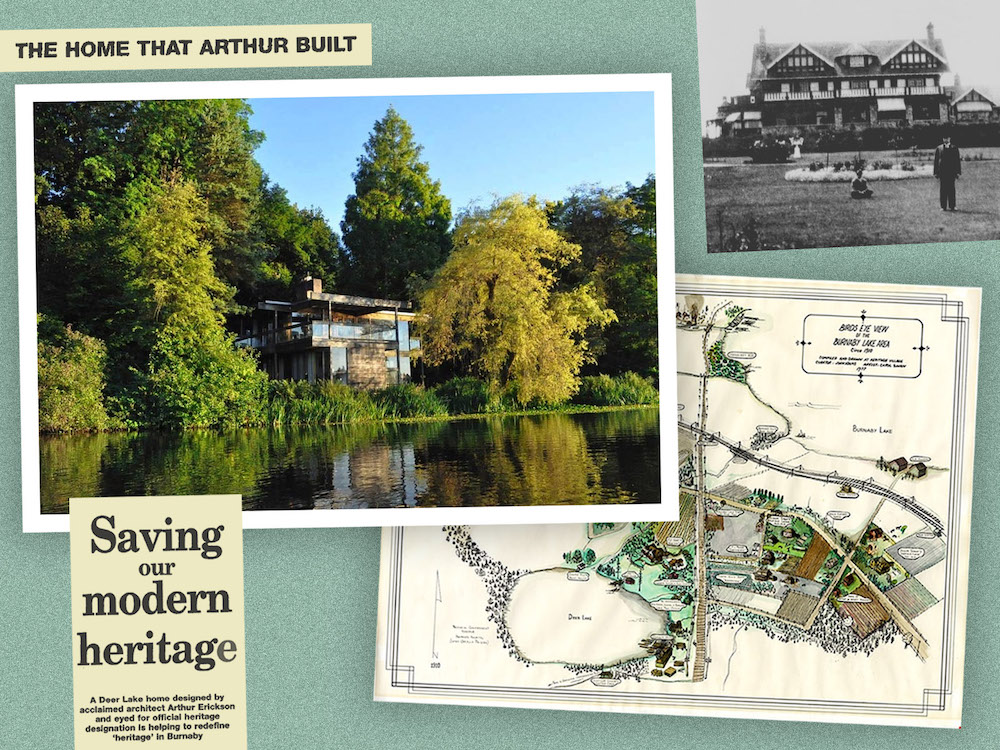

The house tries to hide among the trees on the south shore of Burnaby’s Deer Lake, but it’s too beautiful for that.

Passersby call it “the glass house” for the panoramic panels that stretch from floor to ceiling and wall to wall. With so much glass, the house is transparent enough for nosy hikers on the lake trail to peer into the living room, with its sweeping and enviable views of the water.

Is that sisal carpeting? Is that teak furniture?

Whether it’s your first time strolling by or your hundredth, you can’t help but stop to ask what this modernist gem, the only structure actually on the lake, is doing out here in the wild.

It’s a good question. The house was completed in 1965, back when the City of Burnaby had already begun protecting Deer Lake for conservation.

So how did William and Ruth Baldwin, the owners of the lakefront property, manage to get the permission to build their new house right on a public body of water?

“The city wouldn’t hear of it,” Ruth told the Burnaby NewsLeader. “Finally, I asked a neighbour, who was a lawyer, to help us with it.”

The Baldwins already had the design in hand, but it took four years of wrangling with the city before they were issued a building permit.

By the time the house was finished, it coincided with the completion of another high-profile project by the same architect.

In 1965, Burnaby received two modernist masterworks from the renowned Arthur Erickson: Simon Fraser University on the mountain and the Baldwin House on the lake.

Choosing Erickson was a no-brainer because he was a close friend of William’s from high school at Prince of Wales on Vancouver’s west side. They also attended university together at McGill.

Simon Fraser University, which was designed by the practice Erickson owned with Geoffrey Massey, kicked off work on the many institutional buildings that Erickson would become widely recognized for, including the B.C. Supreme Court building in downtown Vancouver and the Museum of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia.

Before all that, Erickson was known for his work on homes.

“We didn’t want to just look at Deer Lake,” the Baldwins said in a magazine interview. “We wanted to use it.”

Deer Lake cribs

Prior to settler contact, various Indigenous Peoples relied on the lake and its surroundings for hunting and gathering.

E. Pauline Johnson, in her 1911 book Legends of Vancouver, included a story about Deer Lake told by her Sḵwx̱wú7mesh friend Chief Joe Capilano.

In the story, another Chief who bore his name speared a king harbour seal around False Creek, only for it to disappear into an underground river. Months later, the Chief went to investigate a forest fire in the east, where he came upon Deer Lake and found the remains of the same seal and was reunited with his elk-bone spear.

In 1859, settlers began to explore the area. In the years that followed, they established an electric tram and many farms, notably for strawberries. The nearby Oakalla prison, a notorious place where thousands of Indigenous people were held for resisting colonial rule or practising their own cultures, continued this tradition and operated a productive farm on the lake from 1912 to 1979.

Between 1904 and 1935, rich landowners chose the lakeside for their houses, in Arts and Crafts, Edwardian, Tudor and Romanesque styles.

“Splendid mansions surrounded by spacious lawns and grounds soon tell the visitor that this district is one of the choice country residential sections for the wealthy of Vancouver and New Westminster,” read one newspaper report in 1912.

“It’s really an attempt to import a British esthetic into the Canadian landscape, sort of like a colonizing architecture,” Lisa Codd, a heritage planner at the city, told The Tyee.

By 1949, Deer Lake Park had been established on the eastern shore, where the present beach and boat rentals are. Burnaby then began work on turning the area around the urban park into an administrative and cultural centre for the city.

In 1959, the Baldwins bought their Deer Lake property for $16,000. It was 2.5 acres and had an old cottage that was also far from the lake, set at the top of a hill.

Swimming in the lake, Ruth had the idea for a new house unlike the others, one that was right on the water.

The well-travelled Erickson, inspired by the houseboats of Dal Lake in Kashmir, had just the idea for the design.

Inside the glass house

Neglecting the sign that marked the house as private property, I’ve pressed my face up against the windows of the Baldwin House many, many times.

It was only recently that I learned Ruth Baldwin, widowed after William’s death in 1989, sold the house to the City of Burnaby in 2001 in support of its continued mission to acquire the remaining private properties around the lake for conservation. The condition was that it be protected as a heritage item and that she could continue to live in the house. Ruth died in 2009.

The Land Conservancy of BC, which had its offices in the nearby Eagles Estate, another city-owned property built during the heyday of the lakeside’s British invasion, managed the Baldwin House for short-term rentals. A number of the Deer Lake homes that have been purchased by the city have been converted to an assortment of uses, from the Hart House restaurant to the Burnaby Art Gallery.

In 2018, the city began running artist residencies in the Eagles Estate and Baldwin House.

Delighted that the Baldwin House wasn’t a private home, I reached out to the city about the possibility of visiting it. After many years, this trespasser was finally invited inside.

If, like me, you’ve watched the 2006 movie The Lake House, or the Korean film Il Mare on which it is based, you’ll know there’s something magical about lake houses.

In this high-concept romantic drama, Keanu Reeves moves into a glass house on a lake built by his architect father, played by Christopher Plummer. He discovers that its mailbox allows him to send messages two years into the future, allowing him to flirt with Sandra Bullock.

“A truly great structure, one that is meant to stand the tests of time, never disregards its environment,” says the wise Plummer character. “A serious architect takes that into account. He knows that if he wants presence, he must consult with nature. He must be captivated by the light.”

In what is either a magical connection between lake house designers or some gentle plagiarism on the part of the screenwriters, Erickson had a similar ethos.

“Architecture, as I see it, is the art of composing spaces in response to existing environmental and urbanistic conditions to answer a client’s needs,” Erickson once said. “In this way the building becomes the resolution between its inner being and the outer conditions imposed upon it. It is never solitary but is part of its setting and thus must blend in a timeless way with its surroundings yet show its own fresh presence.”

You can feel this as you step into the Baldwin House, as though you’re approaching the lake itself.

Heritage planner Codd and artist-in-residence liaison Barbara Pizzinini are there to welcome me into the house, which is receiving a few upgrades on this October morning ahead of the next artist moving in for a month-long stay. Codd is especially excited about a new power pole and heat pump.

“The house really disappears into the landscape from here,” says Codd.

There is a dome skylight in the entryway that ensures that, in the words of an unnamed magazine in the city archives, “even on a dull day, the Baldwin house sparkles.”

With a post-and-beam construction and an open floor plan, the rooms of the house are like a collection of glass cubes, each oriented towards the lake.

I was hoping for a sunny day, but Deer Lake is sublime no matter the weather or season, and today there is a fog that shrouds the water and the trees. The house, like other works of West Coast modernism, vanishes into the rainforest.

“Part of the reason we can get this view is because it’s a single pane of glass,” says Codd, gesturing to the panorama of the lake.

The glass and the view are part of the house’s heritage value, but that poses a challenge for the city because it means it expends a lot of energy.

“If we were to replace the single-glazed glass with double-glazed, you would lose this transparency,” Codd says.

There are other, less intrusive tweaks that the city is planning to make for the sake of energy, such as putting a second dome over the existing skylight and swapping the house’s many louvred windows for storm windows.

“The dream is always complete public access, but the upgrades you have to do for public use are intense,” says Codd.

The Baldwin House is built on a slope. Descending to the bottom floor, you’re even closer to the lake, with a door that leads to a dock that takes you out on the water. But not so fast — you can’t go out there right now because a huge tree has fallen over the dock. Such is life in nature.

“There was a recent bear sighting here!” says Pizzinini.

Exploring the house, you’ll notice that there are private balconies in every corner. Each of the three bedrooms has one, as does the living room and the play area. Whenever you feel like taking in the fresh air, you can open any one of the doors, step out onto the deck, lean on the railing and be amongst the trees.

The Baldwins had two children and you can imagine the childhood they must have had here, with the best of indoor comforts and outdoor adventure.

Almost all of the furniture is pieces from the 1960s, refurbished by the city: the fibreglass lampshades, the rattan chairs, the couches, the long, cushioned bench that wraps around the playroom walls and the teak tables and consoles, some with water stains from mugs on their surface — reminders from when the house was a lived-in family home.

(I do, however, spot a contemporary item from West Elm, the Mid-Century Mini Desk, in acorn, that blends well with the vintage collection.)

“Apparently, there were lots of really good parties,” says Codd.

You can visit all the heritage houses of Deer Lake in less than 1.5 hours by following a guide published by the City of Burnaby. You can see the anachronisms for yourself, with the modernist Baldwin House amongst early 20th-century copies of styles that would have been at home in Jane Austen novels.

But just as water from around the Central Valley drains into Deer Lake, time and history seem to coalesce here in one big pool: Indigenous and settler, orientalism and modernism, privilege and prisoners, the natural and the urban.

There might not be a magical mailbox here with letters from the past, but you will find layers of history around you on the shores of Deer Lake. ![]()

Read more: Urban Planning

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: