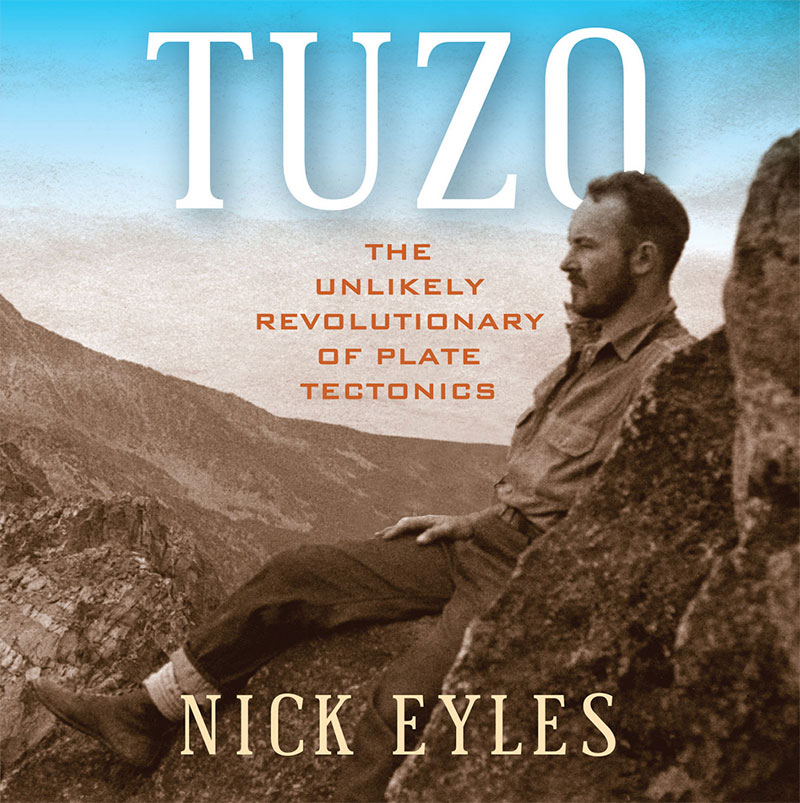

- Tuzo: The Unlikely Revolutionary of Plate Tectonics

- Aevu UTP (2022)

John Tuzo Wilson was born in Ottawa in 1908 and died in Toronto in 1993 after an extraordinary career as an influential geologist, geophysicist, soldier and educator. Tuzo: The Unlikely Revolutionary of Plate Tectonics is a belated biography of a man who identified himself using Tuzo, his middle name and mother’s last name, to distinguish himself from another geologist named John T. Wilson. The wide-ranging book is a history of geology, an introduction to plate tectonics and a study of the anthropology of science — a discipline not always dedicated to the scientific method.

When Tuzo was a young man, that world of science also drew distinctions between superior sciences like physics and inferior ones like geology, his specialty. It was often derided as a tedious discipline, dismissed as “stamp collecting” by those in other fields. After all, geologists gathered samples, estimated their ages and roughed out a sequence of geological eras extending millions of years into the past. But no real theory underlay all those samples.

Still, the Canadian government wanted to know if its northern vastness might contain any valuable “stamps” worth collecting. Tuzo as a young geologist in the 1930s set out on foot, surveying the terrain for resources that could be mined. He learned a lot, but argued that aerial surveys using photography would be far more efficient. He was fortunate in having a father who was a civil servant influential in Canadian aviation. Tuzo’s rapidly acquired skills in photo interpretation then served him well during the Second World War, from which he emerged as a colonel.

Tuzo returned to civilian life as a professor of geophysics at the University of Toronto. The government was again interested in what amounted to high-tech prospecting — looking for valuable resources with new methods and instruments. Tuzo was in the forefront of such activities, training new experts and advocating for them in the halls of power.

His father’s importance in the civil service, coupled with his own wartime success, made Tuzo very effective both in Canada and internationally. He was instrumental in organizing the International Geophysical Year, which ran for 18 months in 1957 and ’58. That job took him all over the world, even to China in the midst of Mao Zedong’s disastrous Great Leap Forward.

Geology’s civil war

From his education to mid-career, Tuzo took part in geology’s great debate — better called geology’s civil war between “permanentists” and “mobilists.” The permanentists believed that the continents were fixed permanently to the Earth’s crust. Mountain ranges were the result of the planet shrinking as it cooled, like the wrinkles in the skin of an old apple. (I remember that analogy in a kids’ science book I read in the 1940s.)

But a few geologists were troubled by the suspiciously neat fit between the west coast of Africa and the east coast of South America, and other evidence that the continents had once been part of a single supercontinent. These were the mobilists, among whom was a meteorologist named Albert Wegener.

North American geology had been dominated by permanentists since the 1870s, with each generation training the next. They ridiculed Wegener because he wasn’t a geologist, and from Germany as well. Another German-born mobilist, Amadeus Grabau, was fired from Columbia University in 1919 for supposed lack of patriotism, and so effectively blacklisted that he had to continue his career in China, teaching geology at Beijing University.

Wegener died on the Greenland icecap while trying to prove his theory, and few mobilists dared to speak up after that. “Continental drift” was considered crank science, and it could cost young geologists their careers to publish evidence for it (assuming they could find a journal that would accept their research). Not that the permanentists had any evidence for a shrinking Earth.

The permanentists rejected continental drift because no known mechanism could explain it. But when faced with fossils of species that had clearly lived on separate continents, the permanentists invoked “land bridges” that had mysteriously risen and sunk by equally unknown mechanisms.

The geologists’ quarrel is uncomfortably similar to the one we have seen in public health since the start of the pandemic, where scientists attack one another over whether SARS-CoV-2 was designed in a lab in China, whether it’s airborne and whether kids can catch it.

Ignoring his own evidence

Tuzo himself, exploring the Canadian Shield, had seen lava intrusions that indicated an expanding crust. Yet he continued to support permanentism and kept ridiculing the mobilists. In his postwar career as a science administrator, he travelled the world and met many colleagues who were willing to consider continental drift; in China, Tuzo found that Amadeus Grabau, exiled to Beijing 40 years before, had trained generations of mobilists.

Still, Tuzo and other North American geologists stubbornly insisted that the continents were locked forever in the crust of the Earth. Fellowships and post-doctoral assignments went to students who accepted orthodoxy, and a tenure-track position was out of the question for anyone who did not.

For Tuzo, the heretical insight burst upon him in 1961 as he stood on the Hawaiian volcano Mauna Loa: the islands of Hawaii were a chain of volcanoes, each younger than the last one. They were exactly what one would expect if the floor of the Pacific Ocean was moving over a permanent hot spot, where magma was rising through the crust.

Even though he was by now world-famous, Tuzo set about gathering evidence for his new conviction.

The most critical evidence came from undersea surveys in the Atlantic that tracked the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Its slopes had once been liquid lava, and before the lava cooled, minerals including iron oriented themselves to the Earth’s magnetic field. It was now known that the field reverses every few hundred thousand years, and those reversals were recorded as magnetic “stripes” in the ocean floor.

Sea-floor spreading was confirmed, and when the sea floor neared a continent it was dragged under — often triggering violent earthquakes in the process.

This is the basis of plate tectonics, which was once crank science and now fully established. As a world-renowned authority, Tuzo Wilson could overthrow the old authorities (and much of his own life’s work); that in turn freed younger scientists to submit their own mobilist research articles to journals that would previously have rejected them out of hand.

‘He’s crazy!’

But some of Tuzo’s colleagues still denied the evidence. The book describes how the head of the geology department at the University of Toronto threatened to dismiss him after a speech explaining plate tectonics. “You can’t,” Tuzo replied. “I’m appointed by the dean.” Another professor told his students “not to pay any attention to Professor Wilson. He’s crazy!”

Nick Eyles’s book works better as a history of the struggle for plate tectonics than as a biography of an influential Canadian geologist. We learn a great deal about Tuzo’s professional career but almost nothing about his personal life; his wife and daughters appear briefly in a late chapter. They evidently put up with his endless travels, often at short notice. So did his students, who often arrived at his lectures only to be told the professor was away on some trip.

His return could be equally disconcerting. As one of his students later said, “it was very hard to take notes from Tuzo because he was so eager to tell the class what he’d just seen, or heard on his travels, scribbling things on the backboard and not finishing the sentence, as yet another thought crowded in.”

Eyles explains plate tectonics itself very well, illustrating plate movement with some dramatic examples. I had not known that the great March 11, 2011 earthquake off the coast of Japan actually moved Japan 50 metres eastward in seconds. Nor did I know that Vancouver Island originated in Central America, and is just passing through en route to its final destination in Alaska.

Disappointingly, Eyles praises plate tectonics not just as superb science, but as a guide to ever more extraction of “strategic metals and rare earth elements.… Traditional energy sources — nuclear, coal, oil and gas — still need to be developed to guarantee energy security in the face of enormous obstacles to powering rapidly developing cities and industry solely from renewable energy sources and unforeseen geopolitical events.”

Perhaps plate tectonics will help us find useful sources of geothermal energy. But if all it does is identify metals on the sea floor and still more fossil fuels, Tuzo Wilson’s insights will only hasten our demise. ![]()

Read more: Books, Science + Tech, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: