[Editor’s note: Surprising, tender, beautifully rendered and funny, 32-year-old artist David Norwell’s first book is an anticipated spring release that hits bookstores today through Heritage House. ‘A Complex Coast: A Kayak Journey from Vancouver Island to Alaska’ is an illustrated travelogue that tracks Norwell’s 1,700-kilometre kayak journey from his home in Victoria, B.C., to Gustavas, Alaska.

Norwell made the journey in 2014, when he was 24 and unsure of his place in the world. “As I survey society, a question barges in,” he writes. “Is this it? Are people happy, or fooling themselves? Is there more than school, job, relationship, house, debt, kids, a family, old age, illness and death? At 24-years-old, I’ve never been asked to dream beyond the conventional-life-checklist or critique the culture we hold so dear.”

The soul-searching kayak journey that arises from his questions brings solitude, a search for meaning and a reckoning with his own privilege.

As summer calls to us on the West Coast, we’re pleased to share an excerpt of Norwell’s new book, an ode to adventure and life’s many wayward waterways.]

Day 2, April 5

Wind light with rain. // Piers to Tent Island — Penelakut and Quw’utsun territory — 17 nm.

Salt Spring Island is my next destination and I hope to get a boost through Sansum Narrows with the flooding tide. Jagged cliffs loom on either side of the channel, I’m nervous. The currents are complex and massive back eddies push the kayak against my will. My arms turn into jellyfish as I struggle to maintain control.

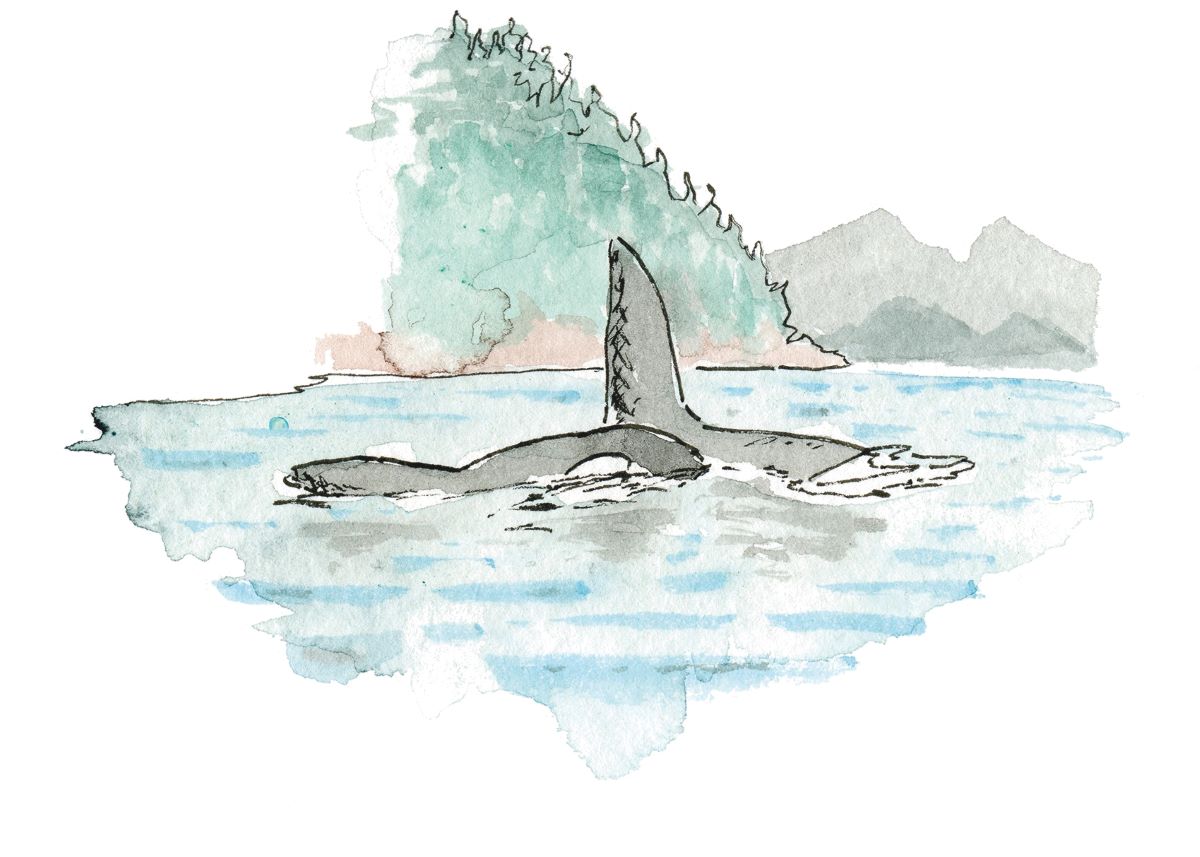

Whales!

PAAWWOOOSHH! Orcas sweep from behind and I’m surrounded by a pod. Sweet Dyna! One breaches metres away, making the boat wobble. There are over 20 — they must be the resident orcas, wolves-of-the-deep. This is the marine apex predator in the Pacific Northwest and they feast exclusively on salmon. However, the transient orcas eat seals and just about everything else. Research shows they are more emotionally complex than humans and have double the neurons in their cerebral cortex. Yet some countries put them in pools to jump hoops.*

The ocean angels guide me through the narrows and disappear, leaving me serene and stupefied. I start crying — my body is shivering. So quickly, I’ve been transported to a world of whelks, whales and whitecaps.

The light is fading as I aim for Tent Island — a reassuring name given my intentions. I’m dog-tired. Darkness falls and one of my sandals is left on the beach as I trudge my gear up. The next morning nothing remains. The tide’s ability to reveal and conceal is beyond any magician.

[* For more details about the whale-human relationship and the aquarium culture/history of Victoria and other cities, see the documentary 'Blackfish.' It stars UVic geography professor Dr. David Duffus.]

Day 3, April 6

Wind light. Sunny. // 6.48 nm.

My morning brain could talk me out of saving the world even if it only required pushing a button. I bully myself out of the sleeping bag. My wrists are sore from yesterday’s race with the whales, so I floss the tendons, pulling the fingers up and back, then curling them down into fists, 20 times (every morning is the plan). Stretch then strengthen. Patient paddling will be the solution.

I procrastinate. It’s late afternoon as I waddle gear to the water, four trips up and down. I leave without doing a check-charley and forget my sunglasses on a log.

Items lost: Sandals x 0.5, sunglasses x 1. Good start.

Paddle, paddle, paddle.

As stars begin their evening duty, I land on an islet the size of a tennis court. No name for it on the chart and it’s ruled by gulls giving off a suspicious smell. Dry wood is easy to plunder and soon I have a rolling blaze.

Tonight’s menu is gruffy: chickpeas, rice, lentils, soybeans, miscellaneous veg, and kelp from the tide line, cooked till mush. I eat in exhausted silence.

The ocean teems with glow-in-the-dark jellies, wiener-biters, and other mysteries-of-the-deep. To swim after sundown is my greatest fear. I resolve to overcome it. My clothing slips off in layers, and I stand naked in front of the abyss.

I repeat a mantra as the saline-universe envelopes my skin and bones: “There is no fear when you let go of everything you know. There is no fear when you let go of everything you know. There is no fear…”

Day 4, April 7

Wind SE 5 kn. Overcast. // Newcastle Island — Snuneymuxw territory — 15 nm.

To co-operate with False Narrows, I pry open the lids before sunrise. This shallow channel floods northbound at four knots (seven kilometres/four miles per hour). Bull kelp stretches below, doing yoga in the morning rays.

On the other side, I rest on a log barge and ram down a couple peanut-butter bars. A humpback whale punctuates my thoughts, then flips its tail and bids adieu. Alone again.

Pelagic cormorants (Urile pelagicus) are underrated. They can dive 60 metres (200 feet) underwater, where they gobble rockfish, herring and even crabs! The northwest end of Gabriola Island is some of the best nesting habitat on the coast. Out of the eroded sandstone matrix (tafone), thousands of streamlined black-backs swoop. They are the fighter jet and submarine of the bird-world.

Newcastle Island is my destination tonight. Once I arrive, the tent click-clacks together in amber light, and I watch the Salish Sea reflect luminous ferries bound for more populated places.

Day 5, April 8

Wind SE 10–15 kn. // Newcastle to Sangster Island — 17.2 nm.

I’ve travelled 70 nautical mamas*, an average of 14 nautical miles (26 kilometres/16 miles) a day. Double checking the chart and the weather, I decide to cross the Strait of Georgia to Texada Island. My first major crossing’s got me a bit heebie-jeebie. A stiff southeasterly pushes me into the middle of the strait. No turning back. I eventually find shelter on Sangster Island, a wonder world ruled by starfish and seals.

“But how do you know the weather?!” I check my VHF (very high frequency) radio religiously; it continuously broadcasts the marine forecast from repeater towers up and down the coast. I scribble the weather down in shorthand notation at the back of the journal. Tomorrow there is a low-pressure cooker moving in, with forecasted 20- to 30-knot blasters. I have never been on the water in such winds. Hmm. What to do? It might be safest to sit this one out.

*Mamas (noun): A unit. Of distance, time or something along those lines. “I’ve paddled 20 nautical-mamas today.”

[This is a “David-ism” and included in the “Davidism Dictionary” on page 201 of the book.]

Day 7, April 10

Wind light. Sunny. // Lasqueti Island — Tla'amin territory — 15.6 nm.

The sea has settled, the storm is over. Dismasted kelp litters the beach.

Day 8, April 11

Wind SE 5–15 kn. // Savary Island — Tla'amin territory — 25 nm.

I dry out in the morning sun and stretch to the sky; my body needs love. Phocoena phocoena (Harbour porpoises) accompany me up Texada, and soon Vivian Rock looms, infested with carnivorous sea lions, brooding. They spot me and go berserker. Barking like dogs, the harem careens into the icy water, popping up in a rabid cluster, battling, nosing closer and closer. I watch in disbelief as one fully ejects out of the ocean, only to be engulfed again in the melee. What the heavy duty… Am I in danger? One thing is clear: I’m not camping here. With the pressure of diminishing daylight, my only option is a seven-mile crossing to Savary: the land of sand.

Why not?

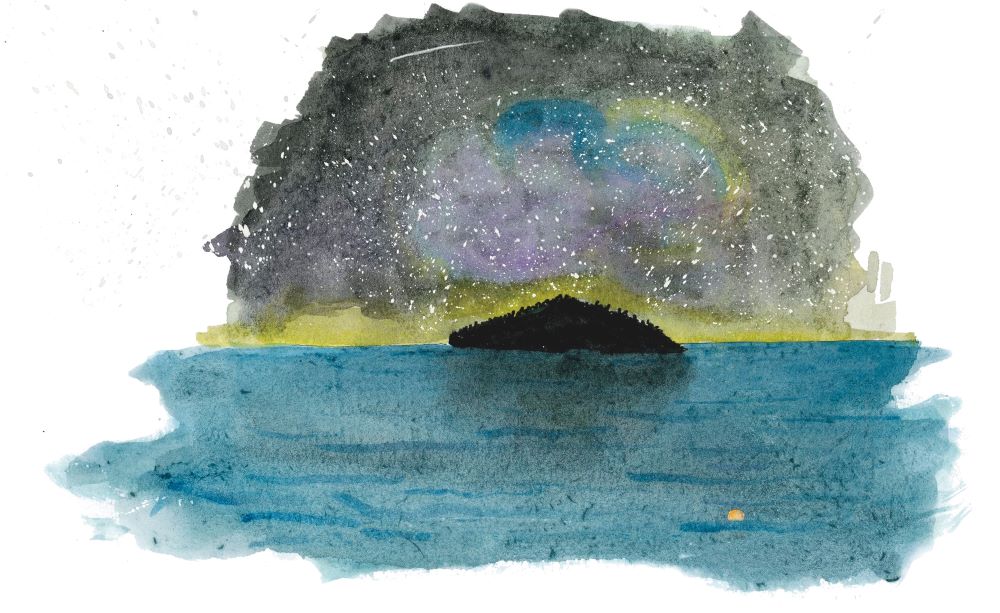

The clouds squeeze the last molecules from the sun. Curious gulls circle and fly off, deciding I’m not driftwood. The seam between ocean and sky stitches; stars smatter the heavens.

Uh-oh. A southeasterly whips up and soon the sea is a whitecap-soup. I begin surfing towards a vague outline. I’m nervous. It’s pitch black, my headlamp is a mere freckle, and no one knows where I am. Onwards.

SPPLLAAAASHHH!

A seagull squawks and an eruption blasts beside me. My vision calibrates — boulders! I weave between and eventually touch sand. It’s low tide and Savary seems far off. Distances are mutated at night. Gathering my gear in the dark, I plod to the driftwood. Food + mouth. I set the tent up backwards, take it down, do it again. Sleep.

Morning reflection: I’ve been saved by some nameless guide. I could have nailed the reefs last night and suffered the fate of many sailors. Thank you.

Harbour seal (Phoca vitulina)

Do you ever feel like you’re being watched, only to spin round and see ripples? These munchkins follow me everywhere, peek-a-booing their beady, infinite eyes. I quite like their curious ways. More than anything, I’m lonely and these philosophers-of-the-deep offer company, however vague and mysterious.

Seals are important because they are hunters and hunted, mediating nutrients from kelp-dwelling fish up to the transient orcas and other apex bombers.

Off Texada, I pass a rocky islet covered in harbour seals. While switching sitting positions I jerk the kayak. Sploosh! My first flip of the trip. The seals plunge into the water and begin popping up everywhere. I scramble into the cockpit. Ahhhh! The term “wiener-biters” comes to mind, and I panic further. Eventually, I slosh in and pump out the bathtub. Jet-black domes stare back. I can almost hear them laughing.

Day 9, April 12

Wind light. Sun. // Cortes Island — We Wai Kai, Kwiakah, Homalco and Klahoose territory — 8.1 nm.

I’ve travelled 129 nautical miles! Pretty neat for nine days.

Cortes is isolated from mainland society by three ferries, resulting in divergent cultural evolution. People here have a practical and philosophical attitude, mixed with a touch of buck-wild. This is due to the ocean, weather and removal from mainline civilization. Everyone wears gumboots, waves and smiles. When in need, your neighbours help — and you do the same.

Cortes is the only place to hold an annual event called Oyster Day (actually “Sea Fest”). I’m staying with my friend Curtis Simpson, who grew up here. His siblings, Henri and Josie, were my roommates in Victoria, and his family has taken me in once before. Curtis invites me on the oyster rafts where he works.

The Gorge is an iconic anchorage on Cortes, scattered with oysie-planks and sketchy sailboats. Bivalve spawn hangs in increments from the rafts, which take two years to grow to commercial size. Once ready, the units are towed in on a high tide and harvested on the low.

We spend the morning processing littleneck clams and the afternoon harvesting oysters. Curty and I get home with a private stash and serious burger inspiration.

Pacific oyster (Magallana gigas)

Oysters live in one of the harshest environments on Earth, the intertidal zone — waves, salt, sun, predators and lots of competition. To prevent desiccation and survive when tides retreat, the shells squeeze shut. I learn they can survive up to three weeks without water! I also learn they change sex depending on the season, can filter five litres of water per hour, and taste different depending on habitat/water quality. Oysters are one of the biggest commercial invertebrate fisheries on Earth — four billion bucks annually.

Oyster burgers

- 5–7 bivalves (from ocean)

- 2 eggs (from chickens)

- creative spice mix (cayenne, salt, pepper)

- 1/2 cup cornmeal (breading mix)

- 1/2 cup flour

- milk

- bunning digs: tomatoes, cheese, lettuce, pickles, love (go full-wild)

- Shuck using necessary means — insert knife in the soft spot at back, and twist.

- Soak oysters in milk for 15 minutes (I dunno why).

- Dunk oysters in eggs and spices (like French toast).

- Bread ’em with flour, spices and cornmeal (coat ’em up).

- Sizzle-fry with oil.

- Bun-time: toppings and condiments (remember: full-wild).

- Nourish (eat slow, and say thanks to the ocean).

- Repeat Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday (as bivalve population permits).

- Enjoy the zinc, calcium, magnesium, protein, selenium, vitamin A and B12 (lots of B12).

- Careful of red tide.

Excerpt from ‘A Complex Coast: A Kayak Journey from Vancouver Island to Alaska’ by David Norwell. © 2022. Published by Heritage House. All rights reserved. ![]()

Read more: Books, Travel, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: