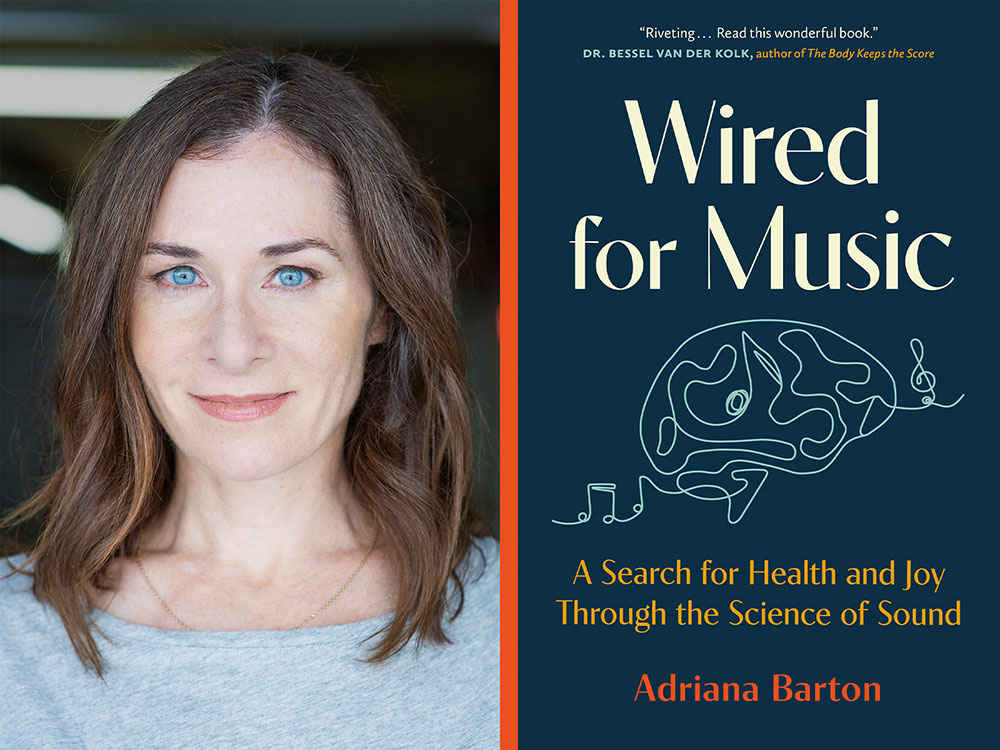

- Wired for Music: A Search for Health and Joy Through the Science of Sound

- Greystone Books (2022)

One day when I was in Grade 5, a kid named David Mason brought an Electric Light Orchestra album to school. Our class spent the entire lunch hour playing "Don’t Bring Me Down" on repeat, dancing like fiends. Each time the needle dropped a bolt of white-hot joy surged through me like a gas flare.

I had a sudden flashback to that memory while reading Vancouver journalist Adriana Barton’s book Wired for Music: A Search for Health and Joy Through the Science of Sound. I hadn’t thought about that song in years, but suddenly I had a craving for some ELO.

Music is some wild stuff. Just how wild is where Wired takes off, looking at how music affects us, on both minor and major scales. From neural networks to social connectivity, music is bound up with the reality of being human in surprising ways. Barton, a freelance writer and former staffer for the Globe and Mail, covers everything from the possible origins of music to recent studies that demonstrate music’s power in helping people with dementia.

Barton anchors the bigger story in the events of her own life, beginning with her early introduction to the cello at age five, where she informed a panel of adults at the local conservatory “I can feel it in my bottom.” As Barton explains, experiencing music as a physical manifestation — the hair on your arms leaping to attention, the glissando slide up and down one’s spinal cord, the fireworks in the pit of your stomach — is a widely shared experience, although not universal. The inability to enjoy music is so rare it's considered a neurological condition.

But of course, it’s never quite that simple. The pure joy that comes from creating and partaking in sound features all kinds of twisted complexities. And in the case of professional musicians, there’s sometimes physical suffering and even a kind of PTSD.

After spending her younger years studying and practicing cello with military discipline, Barton went on to pursue a music degree at the McGill University. A debilitating case of tendinitis and even more profound emotional challenges around the instrument were part of her dropping out of the profession. As she writes, a snide remark from an old boyfriend about her not being a real musician, because she didn’t jam, came after she'd already quit the cello and had enrolled in journalism school, although she still lugged her instrument around like a dead body for years.

Barton’s mother quips that after spending so much time surrounded by the warm, honeyed vibrations of the cello, life must feel pale and grey after leaving such richness behind. Wired for Music charts Barton’s journey back to music through all manner of instruments including the djembe, the ukulele and choral singing. This odyssey is helped along by other associated activities like samba, and even a trip to East Africa.

One of the more remarkable facts that Barton uncovers in her book is the impact that music has on unborn babies. Turns out that even before we come into the world, we’re hardwired for music. As she writes, “the ability to perceive a musical beat, observed in a 2009 study, is ‘functional at birth.’” She adds that the most impactful musical habits, the stuff people continue to listen to throughout their lives, are often embedded deeply during the teenage years. That’s where my love of Prince was cemented. Long live his purple funkiness.

Everyone has their own collection of musical moments: first concerts, wedding songs, heartbreak albums. But as life goes on, the central role once occupied by music seems to become a little less critical. In my younger days, I lived and died for music, squirrelling away birthday and Christmas money to buy new records. My anguish upon realizing that my precious purchase was a dud, with the exception of a hit single, still rings in my ears. I’m looking at you, Rocky Burnette.

One of the best things about music is not only its endless abundance, but the idea that no matter the state of one’s life, old and grey, young and bouncy, it is for anyone and everyone. It doesn’t matter if you’re into metal or Mozart or both. It’s a natural temptation to want to stop in the middle of reading Barton’s book to head off and actually listen to it. Which, in fact, I did, a number of times. But as Barton points out, the way that we do that has changed significantly. Technology, whether in MP3s or even something as seemingly mundane as the Sony Walkman, have had an outsized impact on how we use and perceive music.

Prior to the ubiquity of the Walkman and headphones, if you wanted to hear music, you had to do it out loud. Leaving aside the differences between recorded sound and live performance, a relationship that Barton likens to canned beans as opposed to fresh vegetables, there is a critical difference in insularity that comes from only hearing music inside your own head.

All that collectivity, community and shared bliss is winnowed down to someone bopping along by themselves. “As pack animals, we learned to co-ordinate our movements in game hunts to survive. Rhythmic movements make us feel part of a team,” writes Barton. Even the most basic ways of moving in sync with others fosters feelings of goodwill. When this collective experience is lost or diminished to the individual, does this fragmentation have a deleterious effect on social cohesion? Probably.

Still, in whatever capacity you can take it in, live concerts or streaming services, the benefits of access far outweigh any detriments, especially in the area of mental health and brain function.

Barton writes about how the 2014 documentary Alive Inside: A Story of Music and Memory sparked a major U.S. study to determine whether music could help dementia patients. The study investigated the effects of music on the residents at 265 seniors’ facilities.

Barton describes the results: “Staff members created a playlist for each resident tailored to the person’s musical tastes. After three months, the residents’ odds of needing anti-anxiety medications declined by 17 per cent, and aggressive behaviours by 20 per cent. All from recorded music alone.”

Another German study cites the effect of music on pain management. In the study, two groups of surgical patients were fully sedated for their procedures. One group listened to music through headphones while unconscious and the other heard only silence. The music listeners reported 25 per cent less pain and used significantly less pain medication immediately after surgery. As a painkiller, music’s ability to ameliorate suffering has been long understood and practiced by people around the globe. Anyone who has ever had a transcendental experience while listening to music probably won’t be much surprised that it can substantially affect and even profoundly alter our perceptions and emotions.

The mixture of memoir and science in Wired for Music doesn’t always make for perfect companions. The book’s later chapters, where the author experiments with psychedelics and Indigenous practices as a means of healing, wobble into cliché. The oft-tread terrain of looking to other cultures for wisdom and spiritual knowledge feels a little too pat and easy. But leaving aside these quibbles, there is a great deal to dig into, much of it steeped in the deep and cathartic pleasure that music offers, whatever the circumstances or emotional tenor of a situation.

From childhood lullabies to Grade 5 dance mania, music is a powerful river, able to carve deep channels in the human brain from before we’re born until we slip this mortal coil and go spinning off into the cosmos yodelling disco anthems. For that, and for the thousands of moments of pleasure in between, I am forever grateful. Wired for Music brings many of these experiences back in all of their orchestral splendour. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: