10:30 p.m. at Lucy’s

Vancouver is sleeping, the lights turning off one by one by people in their glassy condo towers. But I’m awake, standing on Main Street, drawn by the neon “OPEN” sign of a small diner called Lucy’s.

I walk across its sticky floors, slide into a booth, pick up a laminated menu and order a $6 bowl of steaming tomato soup with cheesy bread. The fabric of the familiar vinyl seating is ripped, foam pushing out of the cracks.

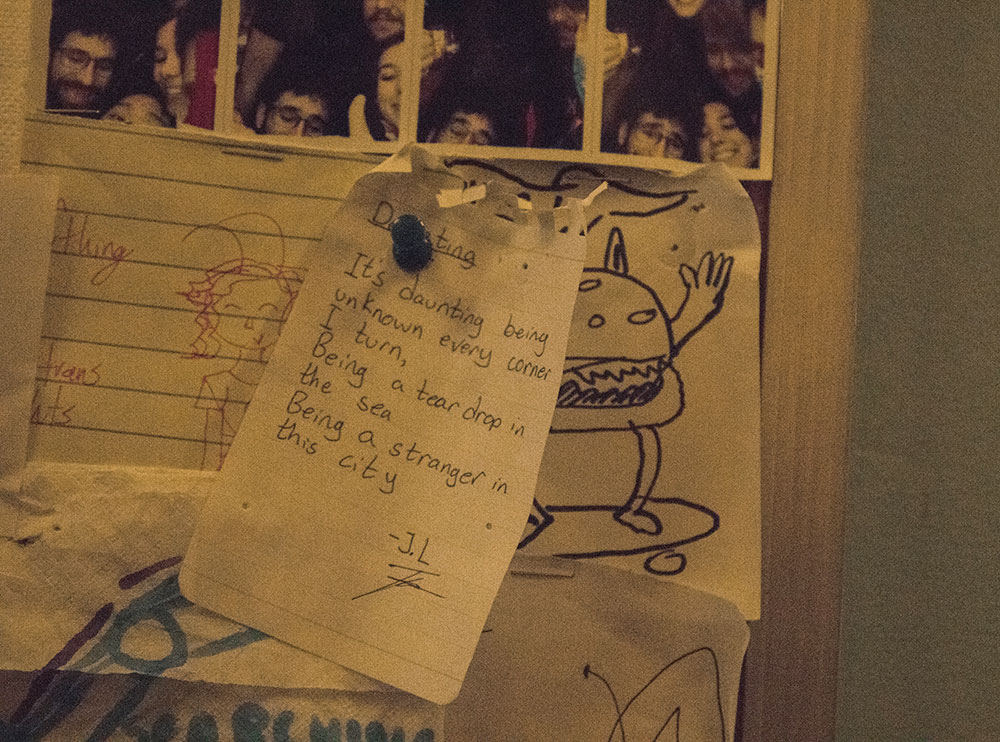

Pinned to a message board next to my booth is a poem signed J.L., scrawled on a slip of paper: “It’s daunting being unknown every corner I turn / being a teardrop in the sea / being a stranger in this city.”

I can appreciate the sentiment — but I’m not alone at Lucy’s.

A woman wearing cowboy boots is sitting at the bar. She orders a junior strawberry milkshake and a glass of wine, and then leans towards the man sitting next to her and asks, “So, like, where did yooouu grow up?”

I lock eyes with another man who appears to be in his mid-20s. I walk over. He’s a sound tech coming out of a live show at Red Gate, a venue just a few blocks down Main Street. His name is Jack.

“This is probably the last time I’ll be at Lucy’s Diner,” he tells me, dipping his fries into a chocolate milkshake. He’s moving to Montreal. He says he has to leave Vancouver — he can’t take who he is when he’s in this city.

I ask if this last visit is a big deal to him.

He nods. “I’m a country boy from Chilliwack who moved to find my way in the big-city music scene,” he says. “I knew it was happening the first time I got invited to the diner after a show. An invite to Lucy’s means you’ve made it in the scene.”

I feel the same way about diners. There’s something about walking through the door of a diner that feels like arriving somewhere. Somewhere welcoming, comfortable and accepting.

“It’s just somewhere to be,” says Simon, a server at Lucy’s. When the rush dies down, I join him on a stool at the bar, where he’s carefully folding napkins and putting them in the black plastic holder.

Simon has served at Lucy’s for years. He took a brief break during the pandemic to work in some breweries in North Vancouver, but returned a few months ago. He loves it here. His favourite shift is from 4 a.m. to noon.

But he can’t work that shift anymore. Once open 24 hours, Lucy’s now opens at 8 a.m. and closes at 1 a.m. on weekdays, 3 a.m. on weekends. It’s the pandemic staff shortage, explains Simon. They can’t get a cook to work the graveyard. No one wants to work those hours, for little pay, in a city with rent like ours, says Simon.

Diners were once staples in Vancouver, as they were in many cities. Greasy spoons were once scattered across the city, serving homemade, no-frills eats like clubhouse sandwiches and soups-of-the-day to those who didn’t have the money, time or reputation for classier establishments. Longtime Vancouverites will remember names like Reno’s and the BC Royal — and the Ovaltine, still standing.

In recent decades, other genres of late-night eats have entered the 24-hour restaurant scene to serve slightly different clientele, from Gold Train’s phở on Kingsway to Richmond’s No. 9, a favourite of Hong Kongers landing after red-eye flights at the nearby airport.

But many old-school diners like Lucy’s that were once 24-7 — from Bon’s Off Broadway to Duffin’s Donuts — have closed their doors to late night traffic. Even Kitsilano’s the Naam Restaurant, an institution established in 1968 that is storied to be the birthplace of Greenpeace, is up for sale. Once open 24-7, the Naam now regularly closes at 11 p.m.

Vancouver isn’t alone in this trend. New Jersey, the “diner capital of the world,” used to be home to dozens of 24-hour establishments, but now only a few remain. In Seattle, the only 24-hour diner is an Ihop.

The death of the late-night diner is a tragedy, says Simon. He believes that a diner serves more than food. With its simple menu, bright lights and unpretentious decor, a diner is a hangout — or hideout — at all hours.

Before the pandemic, Simon’s regulars were firefighters, nurses and cops, people who’d seen stuff and needed a place to decompress before they could go home.

He also serves people who are strung out and just need to feel like “a member of society.” There was the crew that gathered in the back alley for Alcoholics Anonymous meetings. There were the young women who missed the last SkyTrain and needed somewhere brightly lit with warm food and without dark corners.

“We live in a world where it’s hard sometimes,” said Simon. “People just need to feel normal.”

10:50 p.m. at Mary’s

It’s another summer night and I’m standing on the patio of Mary’s, formerly known as Hamburger Mary’s, at the corner of Bute and Davie in Vancouver’s West End. A rainbow crosswalk leads up to a diner of pastel pinks and blues, lit up by strings of fairy lights that hang from the canopy.

Mary’s has been a Davie Street institution since 1979, when it was founded by the Vancouver queer nightclub legend Mrs. G. With a stage in the corner for drag shows and blues, it played host to the city’s emerging yet clandestine gay and lesbian community. Its patio backs onto Jim Deva Plaza, named after the longtime advocate for the LGBTBQ2+ community.

Chef Beth stands next to me on the patio. Her arms — tattooed with a red rose and the name of her mother — are crossed over the railing as she looks across the square lit up by rainbow lights.

Beth has been a cook in Vancouver for 30 years. She’s done it all, from fancy hotel restaurants with linen tablecloths to 5 a.m. shifts at Denny’s. She’s served celebrities like Sharon Stone, who ordered steak and eggs (extra rare for the steak).

But Chef Beth’s favourite place was always Hamburger Mary’s. While fast food options like McDonald’s are open all night, she says the independent diner has a “heartbeat.” Meals are cooked by people whose personalities can shine through at work and you can feel it in the food, a little bit of “pow” and a little bit of “wow.”

“This is the West End, we have fun here,” she says.

Like Simon at Lucy’s, Chef Beth also loves the graveyard shift.

“The world is a different place at night,” she says. “You see people you don’t see during the day. It’s this twilight zone. At night everything’s a go. The daytime is 50 shades of grey, but there’s no grey at nighttime.”

Beth just cooked for a diverse crowd who happened to be out and about late on a Wednesday. That includes Glimmer, a new-to-the city drag queen who is perched on a stool at the bar, picking at tater tots slathered in chipotle mayo, killing time before tonight’s “Drag Me to Hell” show at the Junction.

Back in the 1980s, Chef Beth served bowls of soup to people slumped in booths, knocked down by a strange new disease that was decimating the gay community.

She couldn’t do much, but she could cook.

“I look out here and all I see is memories,” Chef Beth says. “All I see is ghosts.”

She points to the nearby KFC, the Fido and the Circle K. There were once other independent late-night eateries there with flashing neon signs. She remembers when the West End never slept, when it was the embodiment of a set of values and ideas that seemed fringe in a sleepy port city. The West End was so alive with energy, even in diners in the hours before sunrise.

But the new Mary’s closes at 11 p.m.

Their owners are thinking about extending the hours, says Chef Beth. They’re not sure they can afford it with the expensive cost of rent, utilities and staff in Vancouver, but she hopes they’ll do it.

“There’s something important about not shutting doors. It’s like saying ‘We’re here for everyone,’” she says.

11:50 p.m. at Duffin’s Donuts

A semi-truck carrying raw fish roars past the intersection at 41st and Knight Street. Standing at the corner of a residential neighbourhood, Duffin’s Donuts is an oasis for the night owl. Even on a Tuesday night, there’s a line that stretches from the counter to the door.

At the front of the shop is a glass display with rows and rows of freshly made doughnuts: double chocolate, old fashioned honey crueller and rainbow, with sprinkles to match. (Like Lucy’s, there’s poetry to be found, too. This time in the bathroom: someone has etched a Beatles lyric, “See no future. Pay no rent,” on the wall of a stall.)

I order a vegetarian sandwich, walk over to the waiting area and strike up a conversation with the man next to me.

He just got off a shift at Canadian Blood Services. He often works nights, transporting blood from mobile clinics to hospitals across the province, from Vancouver to Nanaimo to Kelowna. Sometimes his shift ends at 3 a.m. and the next starts at 7 a.m. At home, all he has time to eat is a bowl of cereal. At Duffin’s, he can get something warm.

Tonight, he’s just made it before closing. Sometimes he doesn’t make it. Duffin’s used to be open 24 hours before the pandemic and it still is on weekends. But on weekdays, it closes at midnight.

“Hopefully things will get back to the way they were,” he says as he walks out the door.

I pull up a chair at a table and eat my sandwich: $6.50, including cheese and half an avocado. At the table next to me a group of teenage boys are drinking smoothies and arguing about which multigrain bar flavour is best. The rapid-fire conversation quickly turns to fitness.

“I wish I had the physique of Dylan,” says one boy, the others agree.

I ask them why they’re at Duffin’s so late. They tell me that during the summer, they come here three to four times a week.

“In our summers we walk around trying to think of things to do,” says Oscar, who resembles a 1990s Leonardo DiCaprio. “When we can’t think of anything, we come to Duffin’s.”

The boys like the food. It’s cheap and it’s good. Especially the turkey chicken torta and the chicken teriyaki. “Oh, and you can’t forget about the beef steak!” says one.

But they also like people-watching. They tell me that two nights ago there was a firetruck, and a few nights before that there was a man who kept yelling at them to say thank you even though they “like totally said thank you to the server already.” Before that, there was a guy banging on the doughnut cabinet, but then he left, took his shoes off and sat at the bus stop.

They also remember meeting a woman who was a friend of a friend’s mom. They said she offered to buy them beer. They thought that was a little bit weird.

The boys — who have known each other since kindergarten — spend pretty much every night at each other's houses. They say that the supervising parent typically likes them to be home by midnight, but that’s more of a “theoretical” rule. Most likely they’ll be home at 12:45 a.m. But on weekends, they sneak back out to Duffin’s at 4 a.m.

“There’s always something going on at Duffin’s,” said Matt, a friend who showed up late to the party. “It’s not like super crazy stories, it’s just that... What’s the word?”

“There’s eccentric people?” offers Alan.

“Yeah. That’s it. Honestly, I’d cry if I got banned from Duffin’s,” says Matt.

“Yeah, I’d get plastic surgery or something to come back in,” says the DiCaprio lookalike. “Or I’d grow a beard, if I could do that. Which I totally can, because I’m 21.”

The boys are curious about my camera so we go outside to take some “action shots.” While we’re out there, Duffin’s locks the front door. The night is over.

As the boys jump on their bikes and head home, I wonder whether they’ll look back on their neon-lit diner nights the same way I do.

Diners were where I went at 4 a.m. when my friends got a breakup call. A diner is where I ended up after my first night out drinking. (And where I still go to wrap up a night out with a milkshake to cure the hangover that awaits.) A diner is where I found refuge when I was lonely in my city, when I’d left my partner, my apartment and needed a break from couch-surfing and tiptoeing around good friends without a single good thing to say.

A diner demands no down payment, no credit score, no dress code. It’s all familiarity, no frill. At the witching hour, it’s a welcome space for the wounded, weary or curious to sit in a vinyl booth, in the company of strangers, and sip from a bowl of soup. ![]()

Read more: Food

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: