In 1936, members of the Keeseekoowenin Ojibway band were expelled from the newly created Riding Mountain National Park in Manitoba. As the men, women and children left with their belongings for a reserve outside the park, they saw smoke rising from their houses and barns. Park wardens had set the fires to make sure they would not come back.

Removing Indigenous people from national parks and public forests was a strategy that was first championed in 1882 by John Wesley Powell, a geologist, army soldier and explorer who went on to head the U.S. Geological Survey. In one of his government reports, Powell noted that, while an arid climate creates the conditions for fires, it was “Indians” (not white people) who were the chief source of ignition. For that reason, “The fire can then be very greatly curtailed by the removal of Indians.”

This was done in parks such as Grand Canyon, Yellowstone and in Yosemite where the Indigenous people burned to clear underbrush, open pasture lands for deer and bison and to support the growth of woodland crops such as acorns from oak and sweet potato roots.

Indigenous peoples' special relationship with fire began long before Europeans arrived on the scene. As long as anyone can recollect, they used fire to clear the land in a way that would help root vegetables, pharmaceutical plants and berries grow, give rise to lush grasses that favoured bison, deer and other animals and in some cases, drive enemy tribes away from their hunting grounds. To the chagrin of fur traders, they also used fire to drive bison away from the forts so that the traders could not hunt and would therefore have to pay a higher price for meat.

The practice of Indigenous burning was exceptionally sophisticated, and almost certainly prevented larger, more destructive conflagrations from occurring in the future. Fires tended to be lit during cool fall days when they were unlikely to spread for long distances. It was also a sacred ritual.

The Pikunni people of Montana and the Piikani of Alberta, for example, used bison horns filled with mosses, softwoods and hardwoods to carry fire from one camp to another. The vessel was covered in mud and clay and ventilated in a way to keep the fire smouldering. The Piikani could easily have started a new fire, according to Pikunni Blackfeet Elder Marvin Weatherwax. But the practice was more than just a strategy to keep the flame alive. It was a “spiritual” act that spoke to the longevity of the Pikunni and Piikani. Burning the land before leaving camp was a way of keeping the land “clean” so that food and pharmaceutical plants could grow.

Missionaries and explorers such as David Thompson, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark recognized the purpose of this light burning, but farmers and lumbermen who thought nothing of lighting up slash piles on a hot late summer day were appalled, baselessly pointing the finger at Indigenous people when devastating fires such as the one that killed at least 169 people in Miramichi in 1825 began burning with increasing frequency as the Little Ice Age ended, bringing higher temperatures and more lightning to help light fires.

Such assumptions became orthodoxy. Prescribed burning by Indigenous people, to William Greeley, U.S. Forest Service chief from 1920 to 1928, was “evil.” He dismissed the strategy of light burning as “Paiute forestry,” even though it was producing positive results in places like Georgia where it was referred to by white people as “woods burning.”

Wildfire was a “menace,” he said. “We should no more permit an essentially destructive theory, like that of light burning, to nullify our efforts at real forest protection than we should permit the advertisement of sure cures for tuberculosis to do away with sanitary regulations of cities, the tuberculosis sanitaria, fresh air for patients and other means employed by medical and hygienic science for combatting white plague.”

It wasn’t just politics and racism that was behind efforts to stop Indigenous burning. Greeley had the backing of prominent scientists such as Aldo Leopold. Forests couldn’t be productive under light burning scenarios, according to Leopold, because it destroys most of the seedling trees necessary to replace the old stand. Leopold believed that light burning gradually reduced the vitality and productiveness of the forage and destroyed the humus in the soil necessary for rapid tree growth (that is, rapid lumber production, and germination of the seed).

The demonization of Indigenous burning was on display in Canada when the first national park was established at Banff in the Canadian Rockies in 1885. George A. Stewart, the superintendent of what was initially known as “Rocky Mountains Park,” had been a civil engineer and landscape architect until the time of his appointment. He and officials with the Canadian Pacific Railroad were more interested in creating spas, luxury hotels and steam-powered yachts on the Bow River and Lake Minnewanka for wealthy tourists riding in on trains, than on maintaining ecosystem integrity.

To that end, Stewart and Howard Douglas, his successor, were dedicated to the idea of preventing fires that blackened the park’s so-called “ornamental trees.” He frowned on the idea of the Stoney Nakoda continuing to reside in the park. “It is of great importance that if possible the Indians should be excluded from the Park. Their destruction of the game and depredations among the ornamental trees make their too frequent visits to the Park a matter of great concern,” he wrote in his first annual report. “The sight of primitive Indians,” he reasoned, “deters wealthy tourists from coming to the park” — except, of course, when they were brought during "Banff Indian Days" with full traditional head dress, buckskin jackets and moccasins, drumming and behaving in ways that were more quaint than threatening.

Douglas had the firm support of sports hunters and guides who loathed the idea of the Stoneys shooting game for food that they themselves would have otherwise hunted for trophies.

“They have systematically slaughtered the game,” Douglas wrote in 1903. “Let the line be drawn now, if we don’t the game will be gone.” In 1902, game warden George “Kootenai” Brown complained that the Stoney Nakoda “kill more game in a week than all the sportsmen kill in a year.”

Once the process of dispatching the Stoneys began, Stewart embarked on a sprucing-up program, so to speak. In 1887, he ordered 20,000 trees from the American Northwest to address the “want of variety in our foliage,” and the absence of young trees in some places.

While it is possible that the Stoneys were responsible for some of the burning in Banff and other areas, the most identifiable sources of fire were careless railroad workers and the spark-spewing locomotives that took tourists to Banff. It was not uncommon for railway workers to unload smouldering ash by the side of the tracks on a hot summer day.

“It is a matter of regret that fires incidental to the railway construction have devastated much of the country in the vicinity of the railroad and have spoiled much of the wonderful beauty the environs of these mountains,” noted government surveyor J.J. McArthur in 1886. Locomotives shot burning embers from their chimneys. Railroad workers often emptied ash pans filled with smouldering embers onto, or along the tracks. They piled up slash and ties and burned them, often in hot weather when it was easier to light.

Everyone knew that steam-powered locomotives were a problem in Banff, as they were all across the continent. “There are still 4,087 miles of Dominion Government railways and 350 miles of provincial chartered railways in Alberta not subject to regulation and inspection by the Railway Commission, and the fire prevention service applicable to these two classes is not comparable to that applied under the Board of Railways Commissioners,” according to Clifford Sifton, head of the federal government’s Commission of Conservation in 1917. “The result is that on the government’s own railway (the Intercolonial Colonial Railway of Canada), the fire protective service is the worst we have in Canada.”

The Dominion Forestry Branch, which was heavily involved in the management of Banff before the Dominion Parks Service got its start in 1911, knew railroad companies were a problem when officials there issued a report in 1910 noting that railways were “well up in the list of the causes of forest fires.... If they do not lead, they always follow close in the black array.” The author of another government report complained that the railroad companies had “no interest in or care for public property.”

And yet, the notion that Indigenous people were responsible for the biggest fires persisted in many circles. It was easier to do something about “Indian burners,” as they were called, than it was to strongarm powerful railroad companies like the CPR, which was given $25 million, 10 million hectares of free land and a 20-year land tax deferral in 1880 to build a railroad across the country, including across land that legitimately belonged to Indigenous people.

A low point occurred in 1911 when sparks from a train or the burning of slash piles caused the Porcupine fire in northern Ontario, killing at least 73 people and as many as 200.

The Globe newspaper wrote that this “direful conflagration” should “shock the province into demanding adequate means of protection.” The paper did not place the blame on God or on Indigenous people, but on prospectors, “who are inclined to regard fire with indifference”; on settlers “who are unpardonably careless in starting fires to clear their land”; and on railroad companies and pulp mills that leave “slash that becomes almost explosive in dry weather.”

The government, however, wasn’t about to strongarm railroad companies, prospectors and farmers for this and many other fires that torched the country in 1911. Instead, the Dominion Forestry Branch let it be known to newspapers that it was launching a campaign to educate Indigenous people about the “the disadvantages to the natives that follow the burning of the forest.” Plans were being put in place, the newspapers were told, to enlist the natives as volunteer fire rangers. “Handsome badges,” not a salary, were going to be issued to entice them to sign up.

When another Rocky Mountain national park was established at Jasper in 1911, several Métis families that had been well settled there since the early fur-trading days were told to leave. All good people, by most accounts. But they were also wood and grass burners when it came to growing hay, oats and other crops. For a new national park in which fire control and tourism would be a top priority, this would not do, unless of course it was the new Grand Trunk Railroad that passed through the park.

J.W. McLaggan, the chief forest ranger in Alberta, was sent in to appraise Métis land and negotiate a price for their eviction. They could go anywhere except a national park. One couple, Lewis and Suzanne Swift, a Métis woman, held out, allegedly keeping surveyors at bay with guns. They eventually sold to a Brit who had the ill-conceived idea of turning their place into a dude ranch. But they ended up staying in Jasper when Swift successfully applied for homesteading rights and was made Jasper’s first warden. One of the official roles he played was to seal and lock up the abandoned homes of his former neighbours.

There was no end to these evictions in Canada. Indigenous and Métis people were forced out of Algonquin in 1893, when the Ontario government prohibited all hunting. The same happened in the Parc des Laurentides, when the Quebec government issued the same order, and in Stanley Park in Vancouver, where the Squamish village of Xwayxway had been for more than 3,000 years. One notable exception was the Temagami region of Ontario, where the Teme-Augama Anishnabai were allowed to stay because the Department of Indian Affairs had recognized their entitlements. Federal officials even had a plan to have them do “the work of caring for and operating the territory,” an activity that would be “profitable for them.”

But, as historians Bruce W. Hodgins and Jamie Benidickson have so well documented, Ontario government officials refused, viewing the Teme-Augama Anishnabai as squatters and troublemakers rather than rightful landowners. Assistant Commissioner of Crown Lands Aubrey White believed it might be “very dangerous and even disastrous” if this First Nation could manage the forest. His concern was that they might become “enemies and set fire to the forest.”

These eviction policies extended to even the most remote regions of the country. Many Cree, Chipewyan and Métis were all but evicted from Wood Buffalo when a national park was created there in 1922 to preserve the last remaining wild wood bison herds on the continent. Even though a treaty allowed Indigenous people to hunt and trap in the park, federal officials would only permit them to do so if they could prove that they were signatories to a treaty that gave them that right. Many did not have the education or resources to do so. Orders were given to ban forever any Indigenous person who was found guilty of lighting a fire or killing a bison. Some were fined, but it was doubtful they had the resources to pay anything close to the $200 penalty, as posters warned in English and Cree syllabics. The exclusion of fire did nothing to help conserve grass-eating bison.

John Macoun, a botanist working for the Geological Survey of Canada between 1882 and 1912, was one of the few who dismissed the idea that Indigenous people were largely responsible for fires. He conducted the survey that helped establish the route of the Canadian Pacific Railway through the Prairies. “A stump of a cigar dropped on the prairie is much more dangerous than an Indian fire,” he said. And yet, when it was a cigar or some other form of carelessness that started a fire, Indigenous people under the age of 60 living within 10 miles of a prairie fire, or 15 miles of forest fire, were compelled, if ordered, to fight those fires.

Angus Brabant, fur trade commissioner of the venerable Hudson’s Bay Company, was another. In 1922, he wrote to the Globe insisting that it wasn’t “Indians” who were responsible for forest fires; it was “campers, tourists, hunters and transients.” Another reader, a long-time forester, suggested that the government could solve a lot of problems if it made Indigenous people guardians of the country’s forests, rather than keeping them cooped up on reserves.

By the turn of the 20th century, fires on the North American landscape had become fierce and deadly. There was the Saguenay and Ottawa Valley fires in 1870 that forced the evacuations of several thousands of people. Seventeen villages were levelled in Wisconsin the following year, killing between 1,200 and 1,500 people. In 1881, the toe of Michigan burned 1,480 barns, 1,521 houses and 51 schools, while killing 300 people and injuring many others. Part of Pennsylvania lit up at night when fires overran 45 oil rigs as 15,000 men were fighting fires throughout the state and in neighbouring Ohio and New York. Smoke from those fires, and possibly those in Muskoka, may have produced a sky over Toronto that was of such “strange, weird glory” that the New York Times reprinted an article from the Globe describing people’s reactions.

By 1910, California lumberman George Hoxie was advocating a return to the light burning that Indigenous people practiced. The state engineer of California was in favour of it. A lot of timber owners were open to the idea. Officials with the Southern Pacific Railroad company were on board. Even Secretary of the Interior Richard Ballinger was supportive, stating that “we may find it necessary to revert to the old Indian method of burning over the forests annually at seasonable periods.”

Hoxie’s plan may have come into play had it not been for a series of devastating fires on both sides of the border in the summer of 1910. These big burns ushered in an era of wildfire suppression that would leave an indelible mark on the North American landscape for more than a century. Firefighting would no longer be a novelty that most rural Americans distrusted, but a trusted strategy that was no different than the art of fighting fires in cities.

In the half-century that followed the big burns of 1910, various strategies were put into play to reduce fires. An outright ban on Indigenous burning was one of them.

The response to wildfires in North America was and still is cultural. Indigenous people in Canada represent only four per cent of the population. But 40 per cent of the evacuations that result from wildfire involve Indigenous people. Even now, the Canadian government considers it easier to exile these people to cheap hotels down south for weeks, in some cases separating family members from one another, rather than making their communities more resilient to fire.

The situation has improved, thanks in part to the Indigenous communities which have embraced light burning and tree thinning to reduce fires on reserves, and to the fact that Indigenous people have become the backbone of firefighting efforts in many parts of the country.

Yet the past continues to haunt the present. In a survey of Indigenous firefighters conducted by the Aboriginal Firefighters Association of Canada in 2021, nearly half indicated that they experienced workplace discrimination, which included mocking, bullying and being subjected to humiliating jokes. Some refused to report the abuse out of fear of retaliation or because they didn’t think that authorities would deal with it. Even then, most were “satisfied or extremely satisfied” with the work because it was challenging and they liked to help people and communities in need. They also felt a strong responsibility to care for Mother Earth.

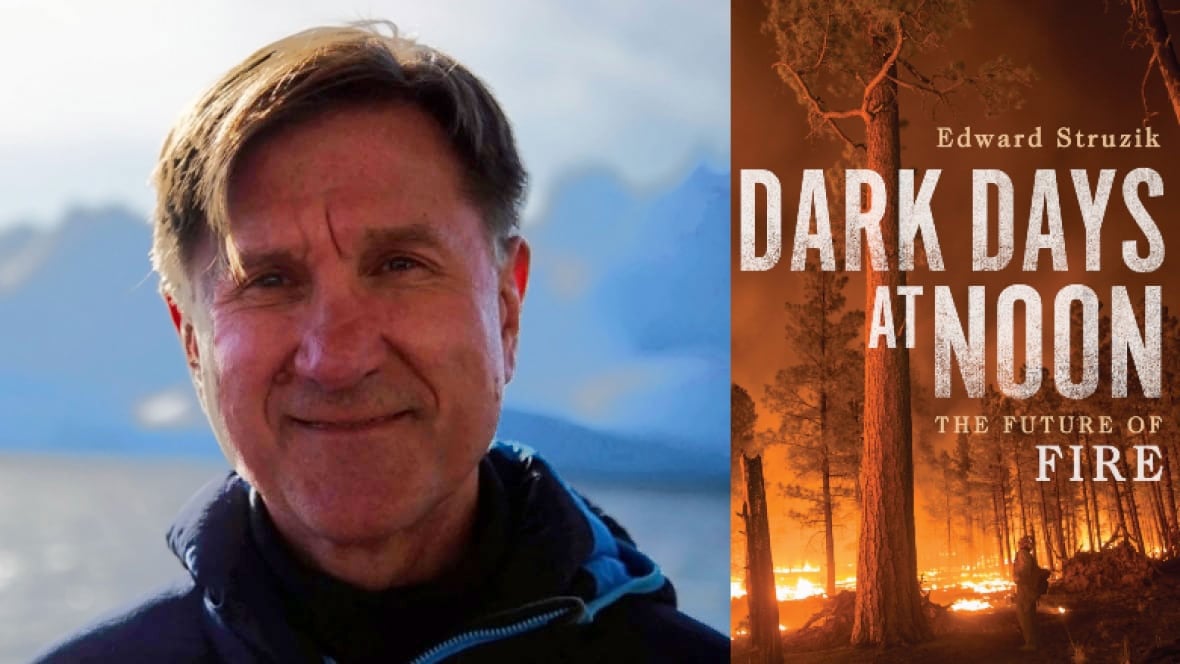

Read a Tyee interview with the author of this excerpt published Thursday. This article is adapted with permission from the chapter titled “Paiute Forestry” in 'Dark Days at Noon: The Future of Fire,' by Edward Struzik, just published by McGill-Queen’s University Press. ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: